School of Rock: All you need to know about ASX tin stocks, ‘the forgotten battery metal’

Pic: Tyler Stableford / Stone via Getty Images

Tin is an essential metal for the modern world.

Used as solder to join circuit boards, a sprinkling of the stuff is in every electronic item you own.

But with a rise in consumer purchasing around the world and supply constraints caused by the pandemic, London-based ‘tin guru’ Mark Thompson told Stockhead the pantry is as bare as he’s seen.

“So what we’ve seen in the last 12 months, is a complete emptying of the supply chain,” he said. “And I would say the tin supply chain right now is as empty as I’ve ever seen any base metal, or I’m aware of, at any point in history.”

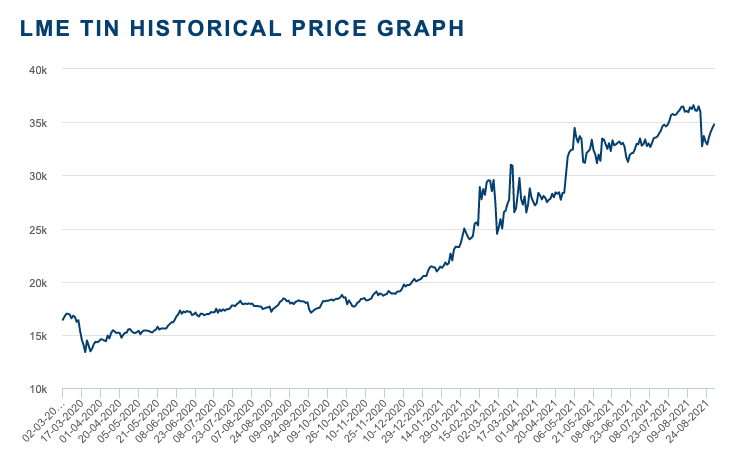

That has seen LME tin prices rise since the start of the pandemic from levels of around US$15,000t to around US$35,000/t.

Some analysts like Fitch Solutions believe prices will subside before the end of the year when operations in Southeast Asia that have been curtailed by Covid restrictions come back online.

But they are predicting demand will begin to outstrip supply again by the end of the decade, and Thompson warns we may need multiple new hard rock mines to fill looming supply gaps over the next 15-20 years.

The question for the market is, where is this going to come from?

Tin: A strategic metal

Tin has always been a strategically important metal, dating back to the Bronze Age when it was combined with copper to make the eponymous alloy.

It took on renewed importance in the midst of the Cold War.

It was viewed as a critical commodity, and one which the US Government was desperate to keep out of Soviet hands.

“So one of the ways the CIA were trying to squeeze the Russian economy was on supplies of tin,” Thompson said.

“Now this forced the Russians to basically send an army of 20,000 geologists out into Siberia pretty much with the instruction to find tin and don’t come back until you have.

“And they were very successful, they found some reasonable sized deposits and by 1961 Russia was self sufficient in tin.”

Over the 1950s the US Defense Logistics Agency built a stockpile of more than 300,000t, almost three times global demand at the time.

“And the US decided that the squeeze had failed, they stopped buying, the price crashed. And because of this price crash, basically the international Tin Council was set up to keep tin prices stable,” Thompson said.

“But then the US Defense Logistics Agency started selling their stockpile and it took them 45 years. And they sold their last little bit of the 4000t that they kept since in 2005.”

The International Tin Council was a group of 22 consuming and producing nations designed to keep the tin price stable. This didn’t work out as the price collapsed from £8000 to £4000 in 1985, the ITC was left some £900 million in arrears to its lenders and fell apart.

“Eventually, like all support mechanisms it ran out of money,” Thompson said.

“And it went bankrupt in 1985 with debts of about £900 million and holding outright physical long positions of 120,000 tons of tin, with derivative positions for another 100,000t.

“So between 1985 and 1991 in real terms the tin price dropped 90% as this price support mechanism basically collapsed. And it took decades for that inventory to get sold off.”

Tin recovery in 2005

Thompson entered the market as a hedge fund manager with Trafigura’s Galena Asset Management, winning big on the undersupply in the market after the USDLA and ITC stockpiles dissipated.

“That’s when I started getting very interested in tin that you had this process where you’ve seen you know, over half a million tonnes of tin sold off,” he said.

“There were no stockpiles. Tin prices in real terms were the lowest they’d ever been.

“So I think the low on tin was around $3,700 a ton. And me being a hedge fund manager we started buying very, very aggressively.

“We bought pretty much all the tin in the world that was left and saw the price go up a factor of five, factor of eight from that level. And as part of that process, we also started looking at equity investments as well.

“So I started looking at tin deposits around the world, tin projects. Since then I’ve probably been to something like 80 tin mines and tin deposits around the world and become a bit of an expert in the tin market.”

Demand supercharged by electronics sector

The International Tin Association refers to tin as the spice element, because bits of it are in virtually everything in modern society.

It is used as a chemical in making flat glass panels, stabilises PVC and plastics, plating for steel cans and is contained in both lead-acid and lithium ion batteries.

But its biggest use by far, absorbing half of the global tin market, is as solder for joining electronic circuit boards.

While miniaturisation has reduced the total amount of tin required in each circuit board, Thompson believes this process is largely over and says the growth of consumer electronics and semiconductor demand will drive demand for the metal higher in the coming years.

“If you go back two years … the tin demand market was around 365,000t, around that amount of 1000t a day,” he said.

“And supply was probably around 350-355,000t in 2019, quite closely matched within a couple of per cent, in a small but not insignificant deficit, which was holding prices in sort of the $15,000-20,000/t range.”

The state of play in 2021

Fast forward to today and tin stocks again are critically low. No one seems to be talking about it, but in the world’s major commodity exchanges – London and Shanghai – just 2.5 days worth of the stuff is sitting in warehouses.

“There’s 2500t in tin warehouses, that’s two and a half days of global consumption,” Thompson said. “If that doesn’t scare you, if that doesn’t scare consumers, I don’t know what does.”

Thompson said demand for tin would be driven by increased use of electronics, the rise of the internet of things and the green energy revolution, which will be driven heavily by electronic technology.

“If you look at the stats and why I’m so bullish on the demand side, there’s something like $500 billion now being committed to new semiconductor production in the next five to 10 years,” he said.

“Now, that’s great, because we all know about the shortage of chips right now, and car production can’t go ahead because there’s not enough semiconductors.

“You know, we’ve all read these stories but people don’t talk about, actually, when these factories come online and the chip shortage disappears, there’s going to be a tin shortage to basically join all these chips together.”

For now, mine disruptions due to the pandemic have cut supply from the 350,000tpa range to around 320,000t.

Buyers are desperate for the commodity and Thompson said some stock that was being sold from stockpiles was incredibly old and poor quality.

“I think some of it I heard was 1960s, Malaysian Smelting Corporation tin,” he said.

“So stuff that has been on the exchange for maybe 40 or 50 years, but that’s all that’s available.

“Slightly hampering things is the LME standard is 99.85% tin, whereas most modern consumers want 99.9 or 99.95. So, people will have to buy what they can buy when there’s nothing else available.”

What can enter the market?

What is in the pipeline to enter the market right now?

Not much says Thompson.

“There’s probably 50 or 60 possible deposits out there,” he said. “I would strongly argue maybe only four or five of them are investable for various reasons.”

There are two main sources of tin around the world.

The first is alluvial sources in places like Indonesia, where small scale miners can extract profitable tin from clays at grades as low as 0.03%.

“Half the world’s supply is alluvial, so onshore and offshore dredging in Indonesia, alluvial mining in Myanmar, and a little bit of semi illegal type mining in Malaysia,” Thompson said.

“You can see some mines in Indonesia, which I visited, running at 250-300 parts per million, 0.03% tin, making a lot of money. Because it’s basically clay hosted, this is decomposed granite with tin in them.”

Good hard rock mines in short supply

The other is the hard rock miners, and with most of the easy stuff mined out already, this is the area where growth is needed to counter looming supply shortages.

But Thompson warns grade is not necessarily king when it comes to tin. Some tin deposits contain high grade tin metal locked within minerals from which it is impossible to extract the end product.

“On the flip side, you can see some hard rock deposits in the world which are around 1% which I wouldn’t touch with a bargepole because they’re either very, very fine grained, you know, sub 50 micron, sub 20 microns as a cassiterite grain size, or they’re not a cassiterite,” he said.

Thompson says cassiterite, a hard crystalline material comprised of tin and oxygen, is the only economic form of tin in the natural world.

“So pure cassiterite runs about 80% tin and you have other tin minerals typically in almost all tin deposits, most commonly stannite which is an iron-copper-tin mineral which runs about 8% tin that has no commercial value because you can’t get the tin out of it,” he said.

“Malayaite which is a tin silicate, again, you can’t get the tin out of it has no commercial value. So whenever you look at a tin deposit, you should never look at the tin grade, what you need to look at is the cassiterite grade.”

The other issue with tin is its coarseness. Tin has a habit of sliming in processing, and the grain size distribution needs to be thick to provide economic recoveries.

“Processing hard rock tin is not easy, you know, you need to know what you’re doing,” Thompson said.

“It slimes very easily. So you’re crushing, your grinding circuit is important.

“And the coarser it is, the higher your recovery will be. And typically, you can’t really recover tin below 20 microns. You really want … your median sizes in your solution to be up around 250-500 microns plus.

“So the coarseness of the tin really, really matters. Otherwise, your recoveries are going to be 10, 20, 30% only.”

Thompson said very few proposed hard rock mines met this criteria.

“Those there are have been around for a couple of decades (have) typically been held in junior mining companies that have been going nowhere, cash starved, and not ready to come into (production) in terms of the quality of the technical work that’s done on them,” he said. “You’d want to look at most of these things and start again.”

Where are tin prices going?

Hard and fast predictions on where commodity prices will end up are always difficult to make.

If current prices of around US$35,000/t hold for a couple years, Thompson said it would provide support for financiers and mining funds to back the development of new projects.

“I think my long term target on tin has always been $35,000,” he said.

“That’s the level where I thought the banks would finance projects. And most of these projects that are out there that are economic need a $25-30,000/t, or more, long term tin price.

“So I think we need $35,000 for a couple of years before the banks and the mining funds will lend to them. But in the interim I’m expecting to see $50,000 in cash in the next six to 12 months.”

But Thompson believes the market could be highly sensitive to future supply disruptions.

“You don’t see bull markets like this without a bit of a blow off top. And I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw another supply disruption to see $100,000, but I’m not predicting that.

“What I am predicting is long term $25-40,000/t, with an average between $30,000 and $35,000, which is what we need for this new hard rock production to come onstream.”

Who has mines to benefit from the tin price today?

According to Thompson tin output has been falling in key markets like China, Myanmar and Malaysia, while many larger and older mines are becoming less productive, like the San Rafael mine in Peru.

Among his personal investments is Mauritius-based, Canadian-listed Alphamin Resources (TSX-V:AFM), which owns the high-grade Mpama North mine in the DRC.

“They’re currently mining at a resource grade of around 4%,” he said.

“It’s off the charts, it’s barely drilled out, I think there’s going to be several mines on the deposit. I think it’s truly, truly world class.”

He said the company, which produces around 11,000t of tin a year, could ramp up production in the next few years, but had logistics risks because of its location.

Metals X (ASX:MLX) owns half of the Renison mine in Tasmania and produced a touch under 4000t in FY2021, swinging from a $12.4 million loss in 2020 to a $24 million profit in 2021 on stronger revenues.

Thompson himself is the executive chair of London AIM float Tungsten West, which is aiming to bring the Hemerdon mine in the UK back into production.

While it will be a tin producer, its main product will be tungsten.

Thompson said another concern for the industry was a shortage of qualified mining engineers, geologists and other skilled mine workers to ensure projects could be planned and built.

“It needs skill sets that probably don’t really exist in the quantities that the market requires,” he said.

“You know, we need to build multiple tin mines doing, you know, 2, 3, 4, 5000 tonnes a year over the next 15-20 years. And those projects don’t exist.”

Metals X share price today:

An under the radar battery metal

Tin is often marketed as ‘the forgotten battery metal’.

“For want of a quick phrase tin turbo charges lithium. So the current best technologies for lithium ion batteries involve tin anodes, which basically allow a recharge much, much quicker than any other technology,” Thompson said.

“So I don’t think anybody knows yet which final lithium technology will be adopted. But tin, I would think, is going to sit in a lot of them, because it has special properties, allowing quick recharge of the batteries.”

Thompson said there’d be more demand on the solder side as well, with EVs expected to have a much higher penetration of computers and electronics than traditional vehicles.

Meanwhile the International Tin Association says tin will also have a big role to play in the growth of solar PV, with solder ribbon used to join solar panels. That represented 7500t of tin use in 2016, with the ITA predicting back in 2019 that the market would almost double by 2030.

Can tin be recycled?

The short answer is yes. The longer answer is only some of it, and it will need a massive amount of investment to fill the looming supply shortfall.

So don’t expect Frank Baum’s tin man to be selling his body just yet.

While technology is improving all the time there remains no way to extract the tin chemicals from things like glass and PVC.

Technospheric mining has been developed in recent years to extract minerals from products like smartphones and laptops.

Steel cans must be recycled by law in many economies like Germany, but then the tin-plating is only a small fraction of the item.

However, tin often occurs in such small quantities it could take millions to billions of items to replicate the equivalent of a very low grade primary tin deposit.

Who owns tin on the ASX?

So with a looming shortage and demand for tin in the electronics sector only likely to rise, who has tin in their back pocket on the ASX?

Iron ore miner Venture Minerals (ASX:VMS) recently restarted exploration at the Mount Lindsay tin-tungsten project near Renison in Tasmania, one of the world’s largest undeveloped projects with around 80,000t in resource.

Silver explorer Thomson Resources (ASX:TMZ) owns the Bygoo Tin Project in New South Wales, which surrounds the Ardlethan mine, the Aussie mainland’s largest tin producer historically at 31,500t.

It is planning a new round of drilling to work on defining a resource after recent discoveries from hits like 118m at 0.43% Sn from 57m depth at the Stewarts prospect and 23m at 1.4% Sn, incl. 4m at 3.52% Sn at P380.

Aus Tin Mining (ASX:ANW) had planned to divest its mothballed Granville tin project in Tasmania and Taronga project in New South Wales as it pivoted to coal, but has since reviewed that decision in light of improved tin market conditions. The $12.7m capped microcap is particularly bullish on the “world class” 57,200t Taronga project.

Brisbane’s Elementos (ASX:ELT) is working on a DFS on its flagship Oropesa project in Spain where it has conducted a major resource definition drilling program, as well as the Cleveland tin project in Tasmania. Stellar Resources (ASX:SRZ) also has an early stage project in Tasmania at Heemskirk.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Venture Minerals and Thomson Resources are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.