Q+A: Greenwing’s Peter Wright on that huge Nio score and why more lucrative deals with lithium explorers will come

Pic: Stockhead, Via Getty

Unconventional lithium partnerships are beginning to pop up between explorers/project developers and carmakers, who realise that there is simply not enough of the raw material to go around.

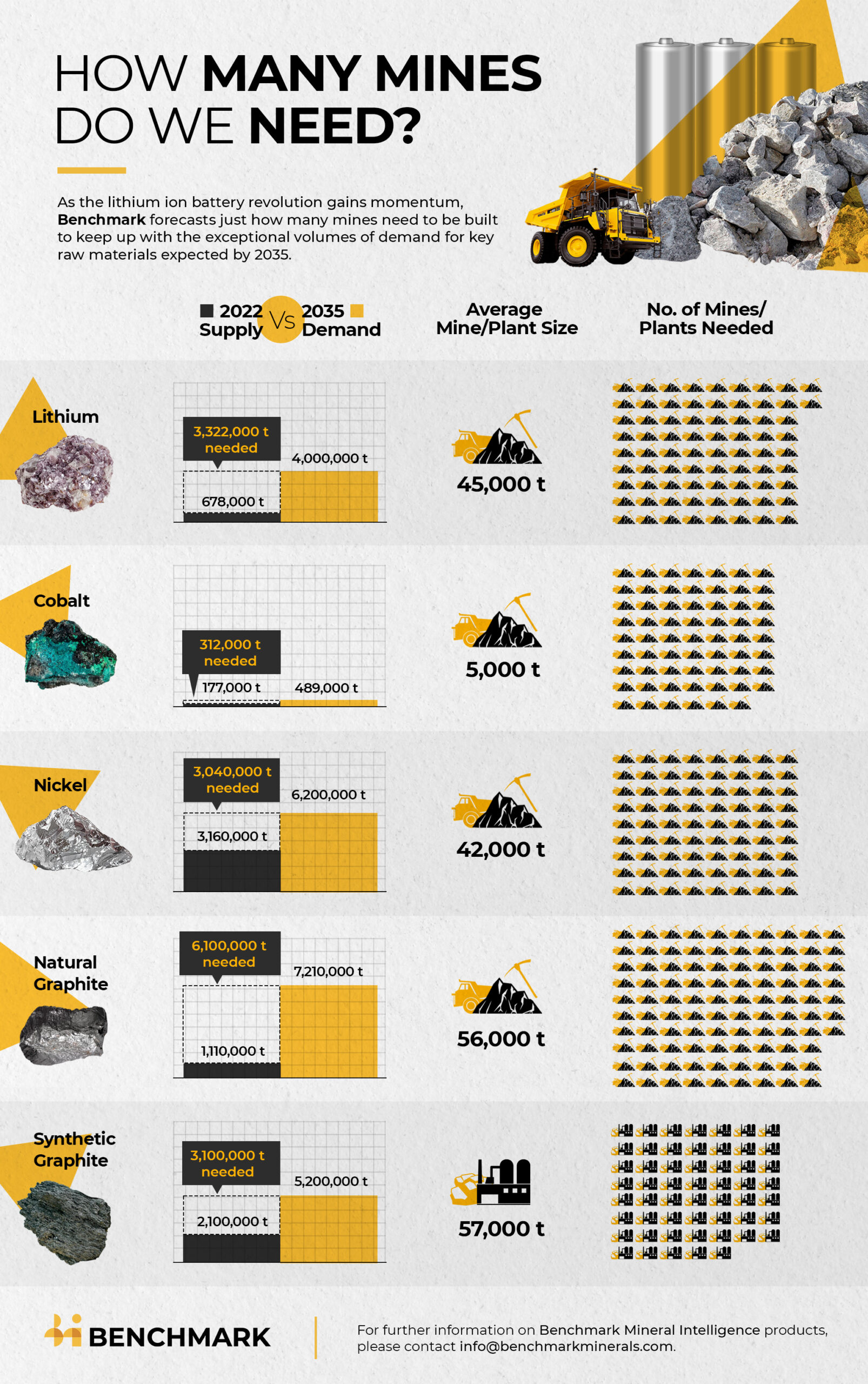

We need more than 300 new mines to feed a 500% increase in battery demand by 2035, Benchmark says.

For lithium specifically, this means roughly 74 new lithium mines with an average size of 45,000 tonnes. A near impossible task.

Securing access to critical minerals for batteries has therefore become even more important.

Earlier this week, NYSE listed Chinese EV maker Nio subscribed for $12m of shares in lithium minnow Greenwing Resources (ASX:GW1), ahead of a potential JV and offtake deal.

Nio will hold about 12.16% of GW1 at completion of the placement, done at 55c per share – a big 124% premium to the last closing price.

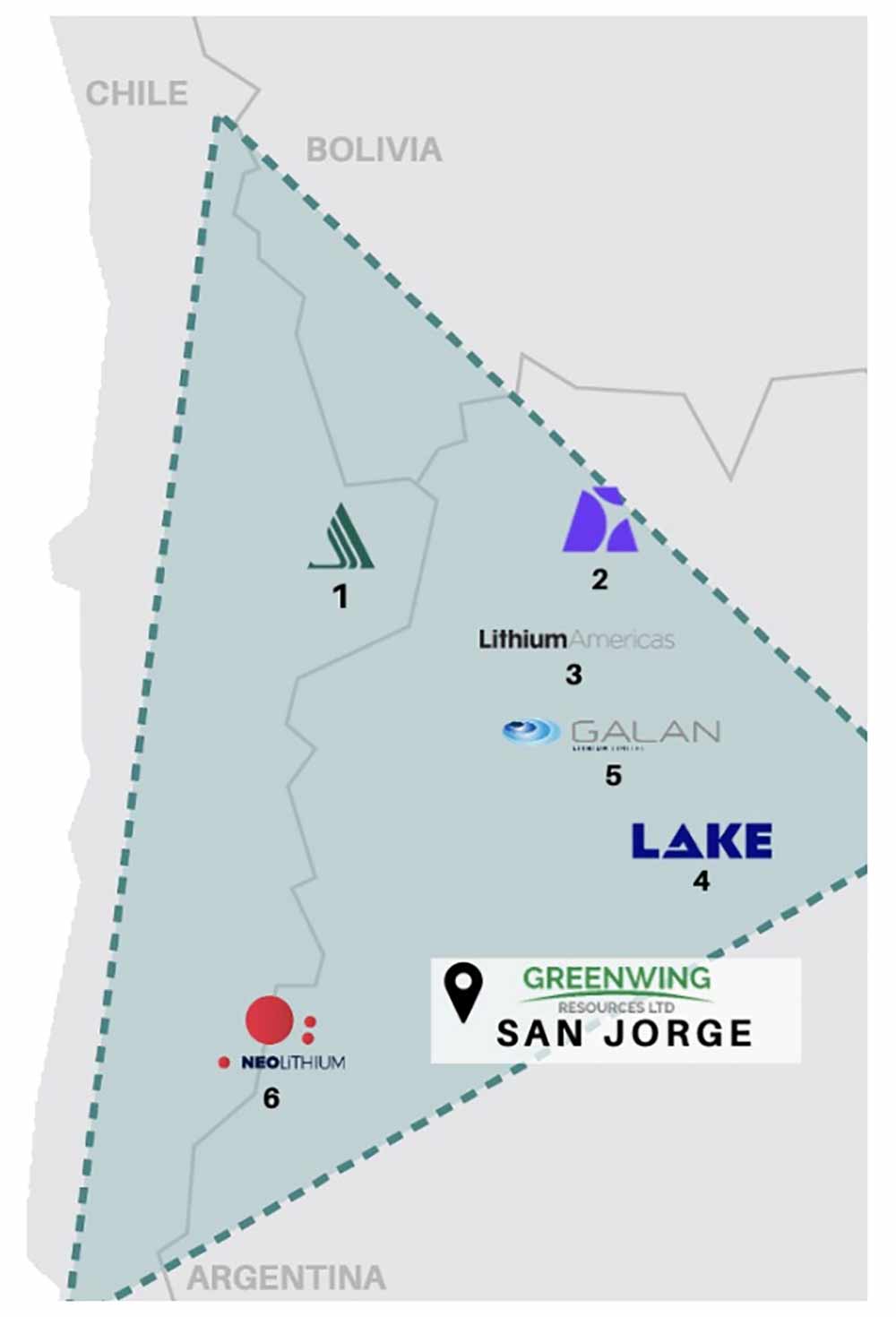

$US30bn capped Nio also gets a call option to acquire up to 40% of the flagship San Jorge project in Argentina’s lithium triangle.

Thing is, GW1 doesn’t even have a lithium resource yet.

Stockhead sat down for a chat with GW1 director Peter Wright to ask – how did a $40m market cap explorer score such a big deal? Can we expect more deals like this between carmakers and explorers?

This is only a relatively recent phenomena – large downstream companies – carmakers, battery makers, chemical companies — partnering with early stage, pre resource explorers. What does it say about the industry at the moment?

“I have been involved in the sector for a while,” Wright says.

“I was corporate advisor to Altura (now Morella (ASX:1MC)) for a long time and it is very similar to that initial boom in lithium, but back then it was battery makers who just couldn’t get their hands on feedstock.

“Now it is automotive companies.

“You look at Nio, which is deeply impressive company. They produced more than 140,000 EVs this year, which puts them ahead of [legacy automakers like] BMW, Ford, and Mercedes.

“They are ultimately looking to go to 1 million units a year from ’24-’25.

“To do that, they, along with all these other global auto majors, are going to need a lot of feedstock.

“Without that feedstock the businesses and their multibillion-dollar supply chains are largely redundant.”

Is this a long-term speculative play for Nio? You won’t be in lithium production in the next couple of years, so surely, they must be thinking ‘if these guys go big, we are in at the ground floor’.

“We have done a lot of work on this project,” Wright says.

“And brines projects are a bit different, so all the [indicators are here] to suggest that this can be a material resource.

“Every surface sample we have taken has lithium in it.

“The geophysics [suggest basin] depths down to 800m. And the TEM survey we just flew would indicate that the brine body extends materially off the western edge of the salar [salt lake].

“There is lithium there.

“There was also an underbidder in this process who are firmly of the view there is potentially something quite substantial here.

“And it is 100% owned. There just aren’t that many 100% owned salars left.”

We have seen similar potential deals announced with small caps guys like Eastern Resources (ASX:EFE) and EV Resources (ASX:EVR). What do you think, more generally, is the criteria these large companies use before inking a deal with a small explorer?

“I think you need to be in the right jurisdiction, like Argentina’s lithium triangle, which is a prolific location for lithium development,” Wright says.

“I think you need to have the right people at board level, and in senior management.

“Our chairman Rick Anthon has been with Orocobre – now Allkem (ASX:AKE) — almost since inception, from a $10m float to the $11 billion behemoth it is now.

“We have James Brown, who is managing director at Morella and on the board of Sayona (ASX:SYA), a $2.2bn company.

“And Craig Lennon, our CEO, ran Highlands Pacific for several years and commissioned the Ramu nickel-cobalt project in PNG.

“Then there’s the quality of the project.

“As I said, we have done a lot of work on this. San Jorge is not a benign piece of ground that may or may not have lithium.

“It is a 1200-hectare salar as part of a broader 35,000-hectare package — a sizable piece of ground, in one of the world’s best lithium jurisdictions.

“I don’t think it get more emphatic than this, for a company of our size to attract a $30bn US market cap car maker. I think they see the potential of the assets and the people managing them.

“In comparison to some of our listed peers we are deeply compelling value wise.”

Do you think we will see more of these deals between carmakers and explorers in the future?

“I do. These global automakers have ambitious targets to deliver into over the next few years,” Wright says.

“Their businesses are largely redundant without raw materials supply.”

Are carmakers panicking about where they are going to get their raw materials from?

“There are a series of reports now predicting an enduring deficit for lithium,” Wright says.

“I think beyond the sloganeering, and as we move to a relatively decarbonised economy, there hasn’t been that general understanding of the supply capacities of the mining industry to deliver what is required.

“From finding your first outcrop of mineralisation to delivering a mine is 6-7 years.

“We built and operated a graphite mine in Madagascar; it’s a difficult process.

“And this is not a linear progression. Just look at funding markets right now, for example.

“Debt has become a lot more expensive, and with the selloff in equities, equity capital is becoming more expensive.

“These impact how quickly mines can be built.

“There is also a lot of lithium and graphite in challenging jurisdictions.

“So yeah, I think there has been an underestimation in general of the capacity of the supply side to deliver on time.”

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.