Pass the salt? BCI maps multi-generational production ambition

Pic: Tyler Stableford / Stone via Getty Images

Once synonymous with Western Australian iron ore, there’s some synergy in BCI Minerals’ tier-one ambition to produce salt and potash on the state’s northern coast.

As BCI (ASX:BCI) pushes ahead with plans for the multi-generational Mardie salt and potash project on the Pilbara coast, the iron ore resurgence means it does so while generating considerable cashflow from a legacy asset on its books.

The Iron Valley mine in the central Pilbara region is operated by Mineral Resources (ASX:MIN) under a royalty-type agreement – MIN covers costs and runs the project, purchasing the mined ore from BCI at a rate linked to realised sale price.

BCI owns the tenements and certain statutory obligations, and pays third party royalties out of revenue received from MIN.

Since the agreement started in 2014, BCI’s annual Iron Valley earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA) from Iron Valley have ranged from $6 million to $23 million.

We all know that iron ore prices have surged in recent times – in the first nine months of the current financial year BCI’s EBITDA from Iron Valley has come in at $37.3 million.

The steelmaking material’s price run was only really beginning at the end of March, meaning Iron Valley could have plenty more to add to the BCI coffers before FY21 is out.

The cashflow is not the main story when it comes to BCI, but for any developer access to cash is key. At present BCI has $100 million of it, with no debt to speak of and quarterly income from Iron Valley, a project with a potential decade worth of mine life ahead of it.

When you have big plans, that’s a big plus.

BCI has some pretty big plans in place.

Meeting Mardie

The big vision for BCI is the development of the Mardie salt and potash project – a tier one asset which would generate annual EBITDA of $260 million over an initial life of 60 years by producing 5.35 million tonnes per annum of salt sourced from seawater evaporation.

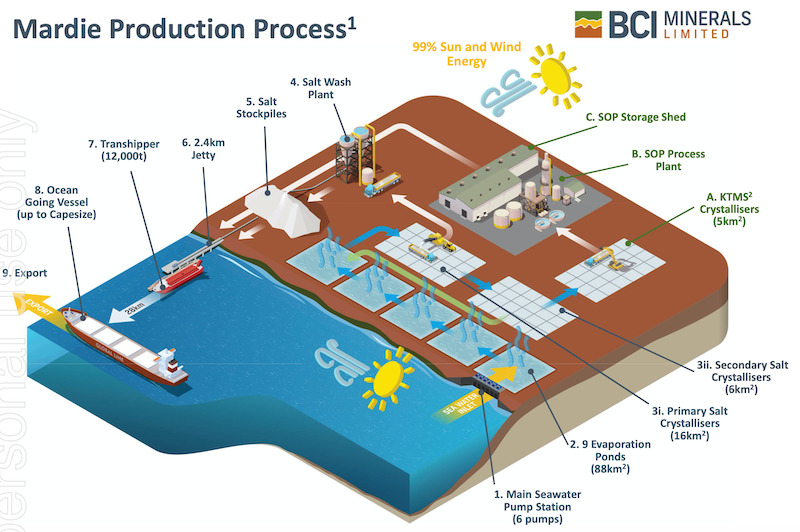

Located on the Pilbara coast between Onslow and Karratha, Mardie will make the most of the region’s combination of high temperatures and winds and low rainfall and humidity to produce high purity salt for use in the Asian market – a region where even when Mardie’s output is factored in, there’s an anticipated supply shortfall of 10 million tonnes by 2030.

Mardie would join five large WA solar salt operations controlled by Rio Tinto and Mitsui, which have been operating for up to 50 years and generate a combined 12-13Mtpa of salt and would be the first project of its kind to kick off for 20 years.

It would be the largest salt project in Australia, and the third-largest globally.

SOP makes Mardie unique

It’s the potash part of the plan for Mardie that makes it different from any other salt project on Australian shores.

Australia does not yet produce any sulphate of potash (SOP), a high-quality potassium fertiliser derived which accounts for around 10% of the growing global potash market.

All other SOP development projects are based on inland lake brines, and more than 800km by road to third-party ports. Mardie, by contrast, sits comfortably on the coast with direct access to planned port infrastructure.

In a market where global demand is expected to grow by 12% over the next decade on the back of growing populations and a need for strong crop yields to feed them, the ability to produce 140,000 tonnes per annum of granular SOP with 52% potassium oxide at Mardie adds considerable value to the overall investment proposition.

The SOP would be produced from the secondary processing of waste brines created during the salt evaporation process.

Words sometimes don’t do these things justice. Here’s how it would look.

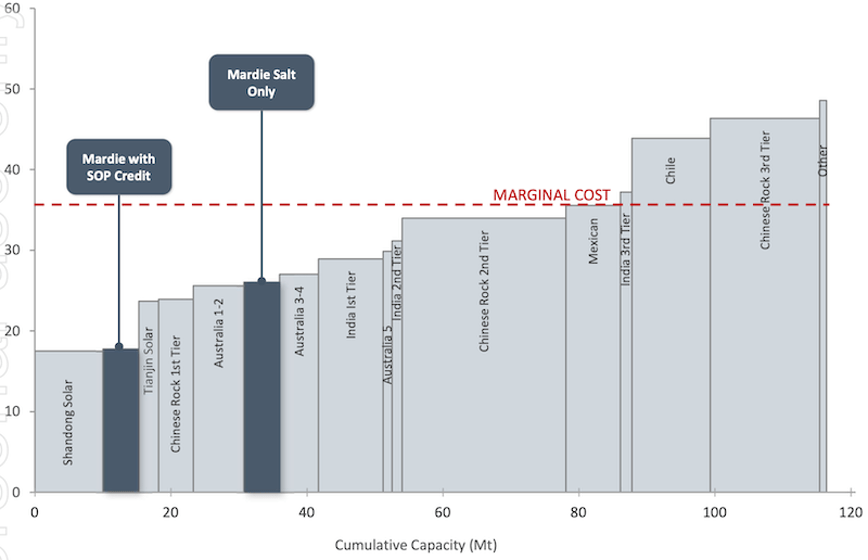

And this is what the SOP credit means for Mardie’s position on the overall salt production cost curve.

A number of MoUs for salt and SOP offtake are already in place, and on the back of an expected final investment decision BCI is looking to convert these to offtake contracts over the next 18 months.

Funding and ESG

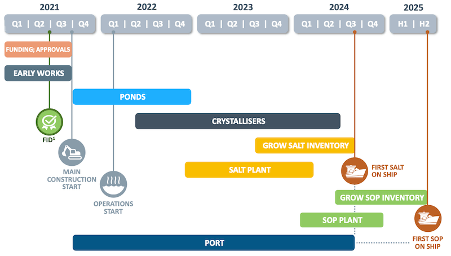

Building a project of this scale does require considerable capital expenditure – the combined funding requirement for Mardie comes in at $1.1 billion, including $850 million capex plus working capital and funding costs.

Seriously helping the cause on this front is recent commitment by the Federal Government of a long-term, 15-year $450 million loan through the Northern Australian Infrastructure Facility.

BCI plans to fund $400 million in equity sourced from existing cash, Iron Valley’s earnings and new capital, and has had positive engagement from banks on the remaining $250 million debt requirement.

One factor sure to weigh into the considerations of the banks is environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG).

An increasingly important component of any investment decision is the environmental and social impacts of a project.

At Mardie, 99% of the energy used by the project would be from the wind and sun, with seawater the resource and waste processed further to create SOP.

The company is also working on a renewable energy and carbon neutral strategy and has key native title agreements in place with a local office established in Karratha.

Given the enormous potential on the cards at Mardie, it’s fitting that BCI’s legacy in WA’s powerhouse iron ore industry could help fund the development of a new, multi-generational and globally significant project on the vast Pilbara coast.

This article was developed in collaboration with BCI Minerals, a Stockhead advertiser at the time of publishing.

This article does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.