On the cusp of a gold boom, this miner’s world collapsed – now it wants justice

Sarama Resources has secured litigation funding to pursue a multi-million dollar expropriation claim against Burkina Faso. Pic: Supplied/Sarama Resources

- Sarama Resources claims its Tankoro 2 permit in Burkina Faso was expropriated by its military government in 2023

- Last week the company secured US$4.4 million in litigation funding to take the case to international arbitration

- ASX and TSX miners have won hundreds of millions in damages for claims in recent years as resource nationalism rises across the globe

When Aussie mining executive and geologist Andrew Dinning wrapped up a successful stint as director and president at Moto Gold Mines in 2009, selling its stake in the Kibali gold mine in the DRC to Mark Bristow’s Randgold Resources and South Africa’s AngloGold Ashanti via a US$578 million takeover, Burkina Faso was the place to be.

The emerging West African country that captured a portion of the 7Mozpa Birimian Shield seemed the logical place to repeat the success.

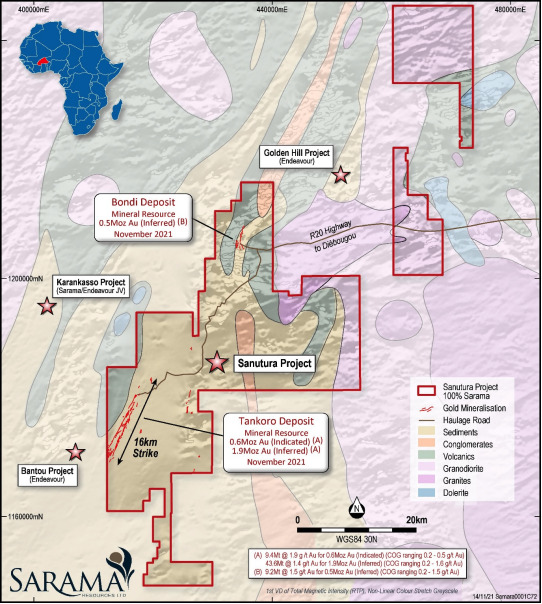

From 2010, Dinning led the exploration of the Tankoro prospect, part of the broader Sanutura project near the town of Hounde in south-west Burkina, turning a greenfields discovery undrilled for 50km on either side into a 2.5Moz gold deposit after sinking US$80 million of investors’ cash into the virgin ground.

“We went to West Africa because of the geological opportunity,” Dinning said.

But a succession of coups in 2022 turned the land of opportunity into scorched earth and his gold explorer Sarama Resources (ASX:SRR) instead became a cautionary tale about the rise of resource nationalism.

Almost one year after the installation of then 34-year-old military captain Ibrahim Traore as president, the company announced on September 6 that its rights to the Tankoro 2 permit had been withdrawn.

“Instead of putting out a feasibility study that shows an internal rate of return of 100% at US$1800/oz, not US$2800/oz, you can imagine what it would be now,” Dinning told Stockhead.

“Instead of doing that we put out a news release saying the government’s taken the permit off us and killed the project,” Dinning pauses … “for pretty invalid reasons.”

Originally listed solely in Canada, Sarama’s shares closed at 19c on their first day trading as CHESS depositary interests (CDIs) in Australia on May 6, 2022, midway between two separate military power grabs on January 23 and September 30 of that year.

By the time the now C$8m-capped explorer reported the expropriation, its Australian CDIs were worth just 3c, closing as low as 1.7c in March this year, the upheaval consuming 91% of their value.

Now, Sarama is ready to fight back.

Action afoot

On Thursday, Sarama announced a litigation funding agreement with Locke Capital II LLC, which will provide a four-year non-recourse loan valued at US$4.4 million to cover all fees and expenses related to its pending arbitration claim.

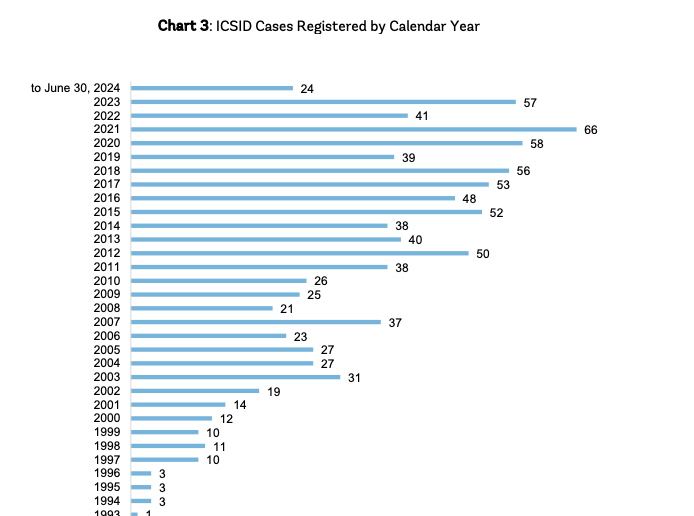

The request for arbitration is expected to be filed soon with the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, a Washington-based court of international arbitration that is seeing an increasing caseload with many disputes related to resource nationalism.

Dinning could not disclose the amount Sarama would be seeking in the claim, but it stands to reason the payout the explorer will chase substantially more than the US$80 million spent at the site across its 13-year tenure.

A material change report filed by Sarama with Canadian regulators in December 2023 estimated the amount of damages to be claimed “to be not less than US$120 million”.

Since then gold prices have surged to new highs.

War in Ukraine and the Middle East and the unwinding of a two-and-half-year-long rate-hiking cycle have set the stage for an epic buy-up of the safe-haven commodity from investors and central banks.

The London Bullion Metals Association reported gold prices in excess of US$2736/oz on Thursday, up over 30% YTD. Banks are increasingly setting forecasts that gold could hit US$3000/oz in the next year.

When the project was taken off Sarama, eventually handed – Dinning said – to a local company, spot prices were ~US$1900/oz.

“Particularly with gold at US$2750 an ounce I don’t appreciate having lost an asset where we’d probably be looking at starting construction late this year, early next year,” Dinning said. “That was always our view where gold was going, that it would trade much, much higher.

“We had a very good project and we would have made a pretty serious amount of money for everybody including the Government of Burkina Faso.

“That’s the absurdity, and I personally don’t think that project will ever get developed now … unless that local company then flips it to somebody that knows what they’re doing.”

Sarama’s shares have lifted ~75% in the past six months to 3.5c as its progressed the acquisition of a new gold project near the community of Cosmo Newberry in WA’s Northern Goldfields, where its attention will turn while the arbitration case plays out.

But every US$10m received in a future award would be equivalent to “5-6c” in terms of the company’s value, Dinning said.

And Sarama has arguably the best man on the case.

Knight in armour

“Speaking in a way that doesn’t waive any sort of privilege, I thought it was an incredibly strong case. Resource nationalism is the reason this entire dispute resolution framework exists.”

Those are the words of Boies Schiller Flexner’s Tim Foden. He’s a blue-collar Pennsylvanian turned London trial lawyer whose team has returned US$110 million to litigation funders in the past year.

In the world of academics and philosophers who inhabit the halls of international arbitration, Foden prizes himself as a courtroom technician, a hands-on barrister who has honed his craft for over a decade.

Foden likes to say he runs cases twice. The first is in front of litigation funders, who take on the risk in the trial process – their payment comes with success in the courtroom and then in compelling the losing authority to hand over the damages. Receiving litigation funding, as Sarama has, is a good indication a case has legs.

His latest successes have come for ASX-listed Indiana Resources (ASX:IDA) and TSX-listed Winshear Gold against the Government of Tanzania in southern Africa, and most recently winning a $490m compensation claim for GreenX Metals (ASX:GRX) over the expropriation of the Jan Karski coal project in Poland by the populist far right ex-government of Jaroslaw Kaczynski.

Sarama will be the first to contest the expropriation of resources in the ‘Coup Belt’, a string of West African states across the Sahel including Burkina Faso, Mali, Guinea, Sudan, Chad and Gabon where civilian rulers fell to military juntas in the years following Covid. Foden says there will be more.

“I thought that resource nationalism was dying down, but then all these coups kicked off in Francophone Africa. And these guys don’t know how to run a country, and they have huge Covid-sized holes in their budgets,” Foden told Stockhead.

“Sarama is really the tip of the spear, they’re the first people bringing a claim and there will be others behind them.

“I think as nationalism grows, so does resource nationalism, that’s why we found ourselves in that situation in Poland. Things have evened out in Poland, they’ve got a more moderate party in charge there, but other countries will follow that lead.”

The back story

When the first coup went down on January 23, 2022 and military officer Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba took Ouagadougou, not much changed for Sarama.

The Tankoro 2 permit was renewed as recently as November 2021 and Sarama conducted over 20,000m of drilling in 2022.

“They were very good results,” Dinning said. “That was setting us up to move into an accelerated development.”

A development study was approved at a board meeting in November 2022, with work beginning the next month.

“After the first coup you could still operate there from our point of view, putting aside the security situation. Then they had the second coup.

“Once he (Traore) got in, that’s when things really started to change in country.”

Dinning alleges the new administration, meeting with Sarama officials, told them Tankoro was a state asset and requested payment to keep the licence.

“It was significantly material to the extent we could not contemplate it from a practical point of view,” he said. “There was no legal basis for what they were asking for.”

Then a letter came saying the application for Tankoro 2, granted less than two years before by the Burkinabe mining authority, had been ‘unsuccessful’.

That sent Sarama into a trading halt, though a window of opportunity to address the impasse emerged with since-ousted Burkina Faso mines minister Simon-Pierre Boussim in Perth for an African mining investment conference.

Instead, Dinning and his board watched on as Boussim told a crowded room at a Perth hotel Tankoro 2 was available for purchase.

“You can’t tell me he wrote that presentation the night before,” Dinning said. “They would have been shopping our stuff for ages.”

A planned $10m raising to take the company through final studies was replaced with a $520,000 emergency raise at just 2c to keep the lights on.

Dinning and his board have not taken a salary since, working in the background on the legal claim, options for the 500,000oz Bondi deposit near Tankoro that it still holds and the acquisition of the Cosmo project in WA, where Sarama’s exploration efforts will focus over the next three years as the legal case progresses.

But he says the impact on the villagers surrounding the mine and reputational hit to Burkina Faso would be even more significant.

“Everyone loses, it’s worse for the local community. When we finally demobilised from the local village where we’d been integrated … for 13 years the villagers cried when we left,” Dinning recalled.

“That’s the impact it had on them, because we provided employment, we provided opportunity, we provided hope and we secured the area.

“It’s just so disappointing for so many people. We’ve lost everything, those people have lost more and Burkina Faso loses in all of this.

“Their reputation is permanently damaged as an investment destination.”

Resource nationalism

Explorers like Sarama are not the only TSX, LSE and ASX-listed companies caught up in the movement.

The world’s 15th largest producer of bullion, the gold industry is critical to the country’s economy, making up 77% of exports, 16% of its US$21bn GDP and 22% of government revenue according to the World Bank. Record gold prices put an even bigger target on the sector.

Endeavour Gold, a London-listed firm and one of the largest gold producers in Africa, last year agreed to sell its Boungou and Wahgnion mines to a company called Lilium Capital for ~US$300 million.

In neighbouring Mali, another ‘Coup Belt’ state, mining giant Barrick Gold faces the prospect of losing its permit at the Loulo mine in 2026.

It prompted a 25% single-day sell-off in $2bn capped West African Resources (ASX:WAF), which has reversed since as gold prices climbed and WAF assured investors after discussions with the government that its Sanbrado and Kiaka permits were secure.

Despite the junta’s rhetoric about exploitation from multinationals, Boies Schiller’s Foden says the reality is even local companies are reliant on foreign capital to build successful mines.

“You can get Western capital with Perth companies that are regulated on a transparent stock market like the ASX, who have corporate social responsibility requirements, obligations and anti-bribery obligations placed on them by their domestic law, or you can allow the Chinese to develop these assets, it couldn’t be a more stark choice,” Foden told Stockhead.

The importance of jurisdiction

A large part of Foden’s work involves not just fighting cases in court, but working with companies on their structure to ensure they’re protected if things fall apart.

“When I meet with Australian companies in Perth, it can be a bit of a crap shoot as to whether they’ve got a holding structure in place to protect their assets, and it’s something that I talk to them about all the time,” he said.

While miners often think about structuring their companies to limit tax liabilities, Foden says this can come at the expense of ensuring your project is protected in a worst case scenario. A trade agreement could be the difference between international arbitration or the local courts.

Sarama is different in this respect since its primary listing is in Canada. A trade agreement to protect Canadian investments in Burkina Faso was put into force in 2017. A clause in the document specifically addresses expropriation and compensation due if the promise is broken.

“Obviously, Tim’s track record speaks for itself,” Dinning said. “We have someone working on it who clearly understands the merits of our case.

“He’s got a track record of prosecuting these things in arbitration courts.

“We’ve got the best guy in the business.

“We’re seeking to enforce our rights under the bilateral trade agreement between Canada and Burkina Faso, we’re going to prosecute our rights to the full extent and we have no intention of backing off at all on this.

“Now being 12 months into the process … the amount of due diligence they (the funders) do is significant. They look at the legal merits, they look at the jurisdiction.

“A lot of these cases fall over on jurisdiction because they don’t have a trade agreement or something to work with. We do.

“They go through everything. I think the fact that they’re prepared to fund this says a lot on their thoughts on getting a return on their investment.”

Sceptics

Foden says there’s a degree of scepticism from investors when it comes to arbitration claims.

“I was always telling people that you could treat these claims almost like a legacy asset. That’s an expression that a lot of family offices like to use. We lost this investment, but should we not try to get some value out of it?” he said.

“Before these guys started to bring claims they would just walk on to the next project.

“And now they have an opportunity with relatively little opportunity cost to bring a claim that can claw back some value.

“And yet the market reacts to that as if it was a big waste of time, as if they should have just walked away.”

The reality, he said, is there are ways to not just win claims for expropriation but also enforce them.

Indiana reached an agreed settlement with the Government of Tanzania for US$90m in July this year for its Ntaka Hill nickel project – 82.5% of the US$109m awarded by the ICSID.

IDA announced the immediate receipt of the first US$35m at the time, with the company now in a trading halt ahead of the expected receipt of the second US$25m instalment.

“That asset was ready to go into development, we had spent more than US$60 million on it and we were progressing scoping studies to take it through into production,” Indiana exec chair Bronwyn Barnes said.

“Somebody has since developed the project, so somebody else did make money out of it. So how could I walk away and leave US$60m of investment on the table and not fight for that on behalf of shareholders?

“Yes it did take a lot of time, but we got there in the end and we’re going to get our sunk investment back with compensation in terms of an uplift for the time value of money and Indiana will be able to return some of those funds to investors then use the remaining portion on our projects in South Australia.

“In the long run it was a great outcome for shareholders.”

Barnes said resource nationalism was on the rise, but that shouldn’t necessarily discourage Australian and Canadian companies from investing in jurisdictions like those in West Africa.

“Let’s face it, it’s not just Africa,” she said, noting the GreenX case against Poland and Rio’s troubles with the Jadar lithium project in Serbia.

“What I think management and boards need to focus on is how best to protect that investment.

“Gone are the days of just rocking up to countries and spending money on assets because they look like great assets.

“A lot more time and effort needs to be spent looking at the structuring of those investments to make sure they take advantage of (for example) bilateral investment treaties.”

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Indiana Resources is a Stockhead advertiser, it did not sponsor this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.