Magnesium demand could double in just 8 years. These ASX stocks are hoping to catch the wave

Picture: Getty Images

75% lighter than steel and 33% lighter than aluminium, magnesium has the highest strength-to-weight ratio of all common structural metals.

It is a key raw material for four important global industries: aluminium alloying (which uses up to 6% magnesium), magnesium alloy for the automotive sector, steelmaking as a desulphurising agent and titanium sponge production.

Like many raw materials, most of the world’s 1 million tonnes per annum of supply (about 85%) is produced by China, which also exports a sizeable volume.

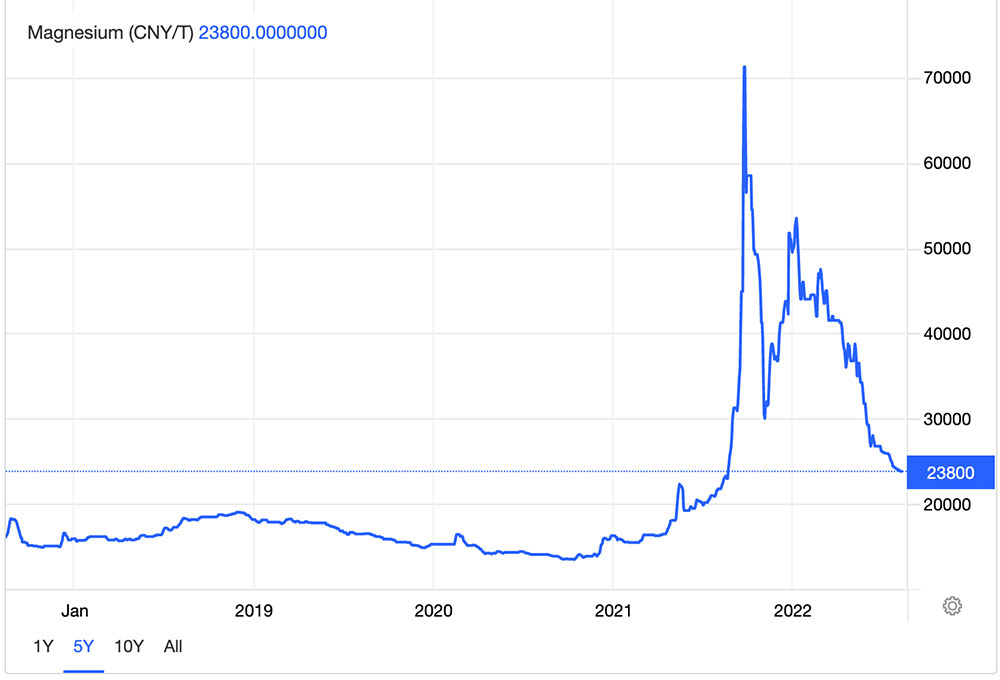

Late last year, the global magnesium market was turned on its head when the low-cost Chinese producers slashed output by ~50% due to ongoing energy sector reform.

Prices went through the roof. In an earnings call, Volkswagen’s head of purchasing said a shortage was expected.

“We cannot forecast right now if the shortage on magnesium, which will happen definitely according to planning, will be bigger than the semiconductor shortage,” Volkswagen’s Murat Aksel said.

In 4Q, German economy will remain under pressure and will suffer from:

1/ #auto production crash amid ongoing #chip shortage and upcoming #magnesium shortage

2/ the spike of energy prices (which also exacerbates #auto crisis)https://t.co/u34t41CbSp

— Christophe Barraud (@C_Barraud) October 25, 2021

It sparked a run by investors on ASX magnesium project developers like Latrobe Magnesium (ASX:LMG) and Korab Resources (ASX:KOR) as buyers desperately looked to diversify their supply outside China.

Producers, like Magontec (ASX:MGL), made a killing.

While prices have now settled back to pre-spike levels, CM Group’s Alan Clark says the volatility is far from over.

“That price spike was driven by the Chinese authorities clamping down on their semi-coking ovens,” says Clark, who has worked in the magnesium sector for over 25 years.

“Many Chinese magnesium producers are co-located with coking ovens, because they supply heat energy at low cost to drive the process.

“So, when the local authorities threatened to shut down more than half the coking ovens because of their poor environmental performance, there was an enormous threat to magnesium production.”

There is a threat of more shutdowns, Clark says.

“There is still some [government] policy which has to be worked through, and we don’t expect to see that until later this year,” he says.

“If the government is just as ruthless in its approach to the semi-coking industry when the policy is next released, we might see another price spike.”

The car sector: a major growth industry

The automotive sector is the key growth area for magnesium demand.

In last four years, aluminium sheet containing up to 6% Mg was used in cars for the first time, as producers look to produce lighter, more CO2 efficient vehicles, near term producer Latrobe says.

“Combined with the surge in EVs, magnesium demand is set to drastically increase as car producers look to ‘lightweight’ heavy EVs,” it says.

“China, the world’s biggest car producer, has a 13-year plan to increase Mg in cars from 8.6kg in 2017 to 45kg in 2030.

“This will generate 1 million tonnes of new demand per annum [alone].”

That’s a doubling of demand in eight years.

While this prediction may be at the bullish end, the fact remains – there is growing pressure on automotive companies to reduce the weight of their vehicles.

Add to this the drive to secure supply chains outside China, and there are numerous new magnesium projects popping up around the world.

“They have been inspired by two things: the spike in prices we saw last year, and the drive to secure a supply of critical minerals, which will become much more important to supply chains in the years ahead,” Clark says.

But BEWARE: the past is littered with failed projects

China production dominates because they use a relatively low-cost and proven, albeit dirty, method to produce magnesium metal.

And that’s where magnesium production differs from other metals, like copper. It is less about the ore feed, and more about the technology used to extract the metal.

“Magnesium is not nearly as much about the raw material [which can come from seawater, magnesite, dolomite, and even fly ash] as it is about the technology and the input costs into that technology,” Clark says.

“That is a critically important part of the magnesium supply equation that perhaps people don’t understand as well as they should.

“One of the advantages for Chinese producers is that the tech used is simple, commercially proven and very well known.

“So the technical risk is so much lower.

“When it comes to competing on cost, global producers are always going to be up against proven, low-cost Chinese production.”

Elevated technical risk has led to notable failed attempts to build Western projects in the past.

Australia had a go at developing a magnesium industry 20 years ago, when AMC raised hundreds of millions of dollars from investors to build the Stanwell project near Rockhampton.

The plus-billion-dollar project was mothballed before it even got off the ground.

There have been others, like SAMAG in South Australia and Magnola in Canada.

“They all suffered a similar fate, none of the projects went ahead in the end,” Clark says.

“The problems were rooted in capital cost overruns, operating cost blowouts and mounting technical risks.

“All three have the potential to cause problems for this next generation of magnesium projects in the future.”

The ASX magnesium project developers set to take advantage

Latrobe has spent +20-years refining its low cost, low emissions technology to convert fly ash from the Yallourn coal operations in the Latrobe Valley into magnesium and a host of other industrial products.

2022-23 is the moment of truth for the company, which is building a 1,000tpa demonstration plant to test the technology at scale.

Once the demonstration plant is operating successfully, a commercial plant will be developed to a capacity of 10,000tpa, which is expected to generate in order of $110m in revenue and EBITDA of $42m.

Longer term, LMG is planning a ramp up to 100,000tpa – about 10% of current global production.

Magontec, already a producer of magnesium products, blew the roof off with an expected net profit after tax of $13m for the first six months of 2022.

“Trading conditions have exceeded company expectations and reflect high underlying magnesium prices, volume growth in some product lines, and higher levels of demand,” exec chair Nic Andrew says.

“Importantly, this record result in the first half of FY2022 means that Magontec Limited has no net debt, as of 30th June 2022, and a robust financial platform.”

MGL has three businesses: magnesium scrap recycling, magnesium anode production and a primary mag alloy plant in China.

It is the primary alloy plant, currently in care and maintenance, which could be a gamechanger for the company.

“We are waiting for the adjacent electrolytic smelter to start delivering us material,” Andrews told Stockhead.

“We think they will later this year or early next year.”

Then there’s long-time battler Korab, which has moved quickly to profit from positive investor sentiment.

In November, it decided to pull the pin on the planned sale of its increasingly valuable Winchester magnesium project in the Northern Territory.

This followed approaches from two separate groups expressing an interest in developing ‘Winchester’, and discussions with magnesium metal users and magnesium buyers, including car makers (Fiat and Daimler).

In May 2022, KOR inked a non-binding deal to potentially supply magnesium metal from Winchester to Speira, a leading global manufacturer of advanced rolled aluminium/magnesium products.

Speira supplies some of the best-known global companies in the automotive, packaging, printing, engineering, building and construction industries, KOR says.

The company is currently engaged in a scoping study evaluating the economics “of an environmentally friendly production method to produce sustainable, zero-carbon, green magnesium metal together with several additional sellable bonus products”.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.