Lead, don’t follow: Real gains will be made in the downturn, says lithium boss

Mining

Mining

Lithium miners and explorers are cutting back, frightened by a +80% fall in spodumene prices last year that decapitated profits and sent smaller players scrambling to raise capital at hefty discounts – or chasing new projects in commodities with brighter near-term prospects like gold and copper.

The latest example came from the stable of Tim Goyder, where newly minted WA lithium producer Liontown Resources (ASX:LTR) is retrenching a third of its admin staff in a bid to trim what little fat there is. 6% spodumene concentrate prices, which hit unthinkable spot highs of over US$8000/t in late 2022, are now trading at US$820/t.

But counter-intuitively, like a body-builder bulking ahead of a cut, the real gains could be made in this part of the cycle when they can’t be seen.

Take a step back and think about Pilbara Minerals (ASX:PLS), arguably the best counter-cyclical investors in the lithium market. They grit their teeth and bore it during the 2018-2020 downturn, keeping the lights on long enough to acquire neighbour Altura Mining in a cut-price deal that immediately added 200,000t of annual capacity to the world class Pilgangoora mine.

At its heyday during the peak of the boom that followed, the combined operation raked in over $900m in free cash in a quarter. PLS’ more than $1.5bn cash balance as of June 30 is the nest egg built from that gambit. PLS has engineered a similar move with the scrip-based acquisition, expected to close later this year, of Brazilian explorer Latin Resources (ASX:LRS).

A handful of junior explorers who listed in the last two years are keeping the faith with the lithium narrative, eyeing the current trough as the right time to set a foundation for the next upswing of the cycle.

A case in point is Chariot Corporation (ASX:CC9), which last week refocused eyes on its Black Mountain project in Wyoming, rising over 20% on Thursday.

“All the money is made during the downturn and then harvested in the upturn. And so I think true to that, we have deployed on that strategy,” CC9 managing director Shanthar Pathmanathan – a former Macquarie investment banker who previously likened the lithium boom to the early days of the oil trade – said.

Part of that conviction has seen Chariot and its 24.1% controlled Mustang Lithium reclaim all of a 10.21Mt LCE claystone lithium project called Horizon after Canadian listed Pan American Energy cited low commodity pricing among its reasons for not stumping up regulatory fees due to the US Bureau of Land Management.

But it’s flagship remains Black Mountain, where attention has again shifted.

Black Mountain, a project so coveted majors rounded it and a prospector reputedly lost a finger through frostbite pegging a claim in the dead of winter, is viewed by Chariot execs as an analogue of LTR’s Kathleen Valley, now a $1bn mine.

There are around 100 outcrops at the top of the mountain stretching for 2km, including areas where 60cm long spodumene crystals grading as high as 6.68% Li2O have been pulled going back to 1997.

CC9’s interpretation is that, like Kathleen Valley, that spodumene mineralisation extends down from beneath the outcrop in vertical structures that grow at depth “like an ice cream cone”.

While initial plans had been to drill for an orebody of the scale of the mega mines found in WA’s Pilbara region, the pullback in lithium pricing and tectonic market shift brought by fast-moving Chinese-backed firms in Zimbabwe has seen Chariot change strategy.

Chariot now plans to define a smaller resource in an upcoming 4300m reverse circulation drill program, leveraging unique Wyoming laws that enable small scale mining developments to fast-track its way to production and generate non-dilutive cash to spend looking for the larger resource at depth.

The plan is to develop a pilot mine with a small-scale, modular plant in a fast start-up scenario not dissimilar to Chinese backed miners in Zimbabwe like Premier African Minerals.

“Those things are one-tenth of the size of Pilgangoora, but ironically, the capex is even lower. It’s ideal from an early stage, small scale perspective to be doing something like that,” Pathmanathan said.

“We’ve hit the ore body at 2m below surface. We’ve hit it at 45m below surface in previous drilling, and we’re not looking for something huge now.

“Our initial target could have been 30Mt, 50Mt but this time we’re looking for a few million tonnes. It’s trying to define something to support feedstock for a small scale mine.”

Wyoming issues small mining permits to operations that remove no more than 35,000 cubic yards of overburden and disturb no more than 10 acres of affected land in any one year, with coal, uranium, underground or in situ mines excluded from consideration.

New or upgraded roads are excluded from the affected land limits as long as they’re within the permit area and bonded for reclamation.

While negative sentiment has surrounded electric vehicle growth outside China, Pathmanathan says inquiries from potential customers and US Government funding programs for domestic battery metals suppliers shows the long-term narrative for lithium remains in tact.

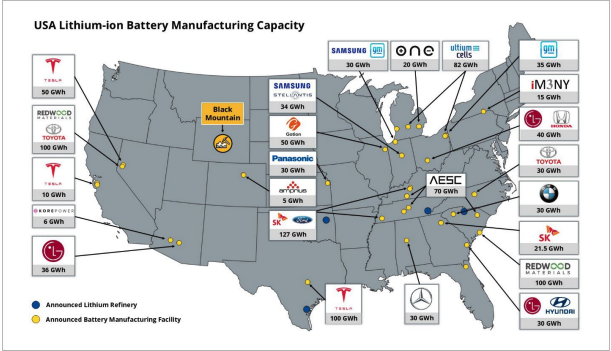

A big part of why Chariot thinks it can be economic at a smaller scale is its location, just three hours by road from Tesla’s Corpus Christi lithium refinery, which is currently under construction and planning to take in material by ship from Liontown’s Kathleen Valley and Piedmont’s share of offtake from the Sayona-operated North American Lithium mine in Quebec.

“They’re going to be buying it from Australia and Canada, whereas our ore is three hours by truck away, as opposed to days, or weeks by sea from Australia for the Australian ore,” Pathmanathan said.

“So we’ve got a cost advantage for any offtaker.”

America produces a little over 5000t of lithium carbonate equivalent tonnes domestically, almost all of it from a single brine operation owned by Albemarle. But according to Fastmarkets, its carmakers and energy storage providers could require as much as 412,000t LCE by 2030, demand growth of 487% on early 2024.

That’s a massive gap to fill that will almost certainly require a staggering amount of government support, such as a US$700 million loan conditionally committed to Ioneer’s (ASX:INR) ~20,000tpa LCE Rhyolite Ridge project in Nevada.

“We’re already seeing that the Chinese car industry is starting to rattle the current car industry out of Japan and the US and I think Western governments are going to have to play ball, otherwise they’re going to get left behind,” Pathmanathan said.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Chariot Corporation is a Stockhead advertiser, it did not sponsor this article.