IPO Watch: This WA iron ore explorer picked a bad day to list, but Pearl Gull is in for the long haul

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

Imagine you own a mining tenement immediately next to the highest grade DSO iron ore mine in history.

Iron ore gets sold from your country, Australia, to China, where more than half of the global steel industry lives.

A pandemic happens, governments juice their economies full of stimulus roids and China’s steel factories go crazy, pumping more iron than they ever have.

Prices rise 15% beyond where they’ve ever been before, the world’s biggest miners are making squillions for their shareholders, some get drunk on the power and think they’re Jesus and you attract $4 million from investors at 20c a share to explore and develop your project in the best market you’ve ever seen.

Then China turns off the taps, the price halves in a matter of weeks and your company’s shares are made available to be bought and sold by the public the exact day iron ore tips below US$100/t for the first time in over a year.

… and it’s a true story

That happened yesterday to Pearl Gull Iron (ASX:PLG), which unsurprisingly lost 12.5% on its first day of trade to close at 17.5c on a punishing day for iron ore stocks.

But as director Jonathan Fisher tells Stockhead, the company is not trying to rush into production and capitalise on the here and now. Its aim is to drill and uncover a mine that will stand up to a sustainable iron ore market.

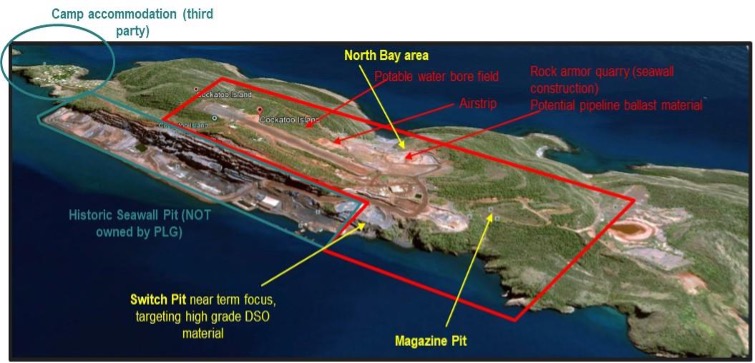

It owns the mining lease immediately next to the Seawall Pit mine on Cockatoo Island in the Buccaneer Archipelago, a northern outpost off WA’s Kimberley coast where dense iron ore was first found by pearl luggers, and where mining giant BHP first mined iron ore in the 1950s.

The Seawall Pit produced some 45Mt of iron ore between 1951 and 2012, with direct shipping grades as high as 67% iron ore, well above the 62% benchmark fines grade.

Pearl Gull has reason to believe some of that mineralisation continues onto its ground, and is closely watching the nearby Koolan Island mine, about 5km away, which is being revived by ASX-listed miner Mt Gibson Iron (ASX:MGX).

This is probably something that’s a little bit unavoidable, but the price of iron ore has gone down considerably between when you were planning the IPO and raising the money to now. Do you feel like you’ve had a little bit of bad luck with the timing of the float?

“Look, I think it’s fair to say we could’ve picked a better day. But, you know, we’ve been working on this project for quite a while.

“It’s been a good many years and actually, when we first started working on the project, the iron ore price was much lower than it is today.

“I think people have been sort of lulled into a false sense of expectation. From a seriously high and unsustainable spot price of over US$200/t to around the US$95-100 where it is today or where the forwards are, that’s still a pretty damn good price.

“And when you factor in a relatively weaker Aussie dollar at 72 cents, that’s a great Aussie dollar price for iron ore; everyone makes money.”

I imagine the idea is about establishing a resource and establishing a project that perseveres at any sort of realistic iron ore price scenario, rather than what we’ve seen in recent times where, you know, juniors have taken on cash costs of $120 plus.

“I think the first thing to know is the importance of grade.

“Cockatoo Island has a history, not on our tenement but on the tenement next door, of producing the highest grade iron ore in the world.

“And what does that do? It gives you a massive price premium, which is obviously, you know, cash costs are one thing, but really what you’re looking for is gross margin.

“So grade, number one. The other thing about Cockatoo versus other juniors who are looking to suspend is their transport costs to get to port.

“Inland transport is often the largest cost for these junior miners and the inland transport costs of something from Cockatoo Island is negligible.

“You literally roll the ore down the hill. So there are some benefits, obviously, that we have in terms of grade and in terms of closeness to water that others don’t have.

“And what does that mean? It means that in any reasonable and sustainable iron ore price environment, we should make money.”

How do these prospects compare to the historic Cockatoo Island assets in terms of the level to which they’ve been explored and the results that previous explorers have had before you?

“So the nearest term opportunity for us we call the Switch Pit, that was actually previously effectively an old ramp access into the historic Seawall mining pit, which is owned by a third party, that’s not our tenement.

“But you can see the continuation of the historic, Seawall Pit mineralisation coming across onto our tenement. So that’s great, because you often don’t get visual cues when you’re doing exploration. There’s some pretty good confidence there is ore there and that is the same type of mineralisation. And therefore, you could interpret something around that at a similar grade to the historic Cockatoo, which is extremely high.

“That’s a small nodule of iron ore that sitting there that you would look to take out relatively short term.

“What we then see is our other two projects in North Bay and Magazine are I guess what you call mine life extension opportunities to pursue after the near term ore at Switch Pit has been mined.

“North Bay has not been drilled before but there again there are visual clues along the way.

“The Magazine project does have some historic RC drilling in it, but you’re not able to define a JORC2012 compliant resource off the back of that.

“So we will be sinking a couple of holes in there as well, looking to bring that up out to a standard which could possibly report a resource in compliance with JORC2012. Magazine looks like from the current historic drilling that it would be more of a beneficiation grade resource.

“And what’s interesting is there actually was a beneficiation plant that successfully operated on Cockatoo for many years. Some of the low-grade ore did upgrade very successfully to a 65-66% product.

“And that’s quite different to Pilbara ores, where trying to beneficiate and get more than a few per cent gain on a Pilbara ore is very difficult.”

When you look in terms of the money that you’ve raised, you’ve got $4 million from the IPO price at 20 cents. And you did say that that was oversubscribed, when you raise the money as well. Where does that get spent over the next two years?

“We’ve been drilling since July, that was announced in the prospectus.

“And obviously being up north there, you’ve got a drilling season. So we’ll be drilling for as long as we can.

“We should probably be probably till late October-ish, I would expect, and then during the wet season it’s just not possible to drill up there.

“We’ll be receiving assay results, doing interpretive modeling, planning, all that kind of good stuff. And to the extent that we obviously need to do confirmatory drilling or more drilling we’ll continue that over the next drilling season.

“Those IPO funds see us through doing all that. Obviously, if we look to develop, we’ll raise capital for that.”

The other thing that I guess is maybe a little bit distinct from other iron ore companies is the potential for producing subsea ballast and quarry rock as well.

“So this is a really interesting opportunity and it goes towards your pit shell design.

“The geology on Cockatoo, it’s an island, it’s hilly.

“In mining, always the key is a strip ratio, how much waste you’re mining and so any opportunities you’ve got to turn otherwise non-payable material into payable material, when you change that in your block model that can totally change and optimise your pit shell design and therefore allow you to get more iron ore out of it and make money.

“You know one of the things about that material at Cockatoo is it’s dense, it’s heavy, it’s competent. And it’s actually one of the few disturbed areas capable providing quarry material in that North West region of Western Australia, which is close to oil and gas fields.

“So historically, some of the ballast used offshore in the North West Shelf has actually come from as far away as Scandinavia.

“That doesn’t make sense, we’ve got a perfectly good rock quarry there on Cockatoo. And to the extent that we can take that material out, for a small cash margin you make some money and diversify slightly away the iron ore price.

“But the key issue is you might be able to completely change your pit shell design. So that’s really interesting.”

Your neighbours have the Seawall Pit which needs to be pumped out after the last owner there Pluton Resources went into administration, is that right?

“I think in my view, we’ve got the best of both worlds, because we can see the benefits from that old Seawall Pit, we can visually see the continuity of the orebody onto our tenements.

“So we kind of get a bit of it without having the historic, massive environmental liability that Seawall pit presents.

“We see it, we can see across our tenements all the good stuff. And hopefully, we can actually be in production sooner because we don’t have to spend a long time dewatering a pit.”

It’s a bit different as well, you’re sort of mining in towards the middle of the island.

“So what’s interesting there is there’s a bit of nearology.

“Koolan Island’s we’ll call it five clicks away to the east, and you look at what what MGX has done at Koolan, and you say, well, you know, can we can we do that on Cockatoo.

“And you get where the Mullet, Acacia and Eastern and Barramundi Pits are through the middle of the island on Koolan and you look to Cockatoo, and that similar area on Cockatoo has never been drilled.

“That’s what we looked into in the North Bay area. You know, the islands are quite similar.

“They both have the Cockatoo formation, with the hanging seawall pit down the side, they both have a pit that goes underwater.

“The question is, well, does Cockatoo have the same kind of deposit up through the middle of the island as Koolan does? What’s interesting when you look at Koolan is a couple of things, first of all, I believe they’re having a look there to see if they can take any more ore from there.

“The second is they are small poddy kind of pits. It’s not like one large mineralisation band running through there, they’ve obviously mined out several pods along the way.

“And so, again, when you look back at Cockatoo you’d expect something similar whereby if there is the high-grade repeat there it’s not going to be a massive long line. It would be poddy deposits of it, similar to what you’d find in Koolan, that’s our theory anyway and it’s what we’re exploring for.”

If you look at Cockatoo in terms of the history and we know about the 45 million tonnes of high grade production that’s come out of there over the last 60-odd years. And in fact, wasn’t it one of the original iron ore exporters out of Australia?

“It was BHP’s first iron ore mine in WA I think. It’s interesting if you know the history of Cockatoo and how it was discovered.

“And actually, it comes into our name Pearl Gull. The Pearl luggers, who came out of Broome and serviced the pearling industry used to stop off at Cockatoo and pick up this bloody heavy black rock that they used to use as ballast in the boat.

“And that’s how they’ve been discovered. What is this super heavy ballast, oh it’s almost pure iron ore.

“There are stories going back in the early days, with people saying the ore was so hight grade you could actually weld it; I don’t know if that’s true or not but it is extremely high grade.

“So the Pearl Gull was one of the pearl luggers that used to service the Broome pearling industry and used to stop off at Cockatoo for ballast.

“Obviously, BHP then found larger and more easy to mine deposits in the Pilbara at scale. And at a time when iron ore pricing was way lower than it is today they decided to discontinue operations on Cockatoo.”

The high grade aspect, does that excite you from the macro perspective of – obviously premiums at the moment are contracting because the price is going down – but there is that expectation long term that higher grade iron ore will continue to attract the premium and that could grow as you know, steel production needs to get cleaner?

“So you hit the nail on the head, right? It’s a long term thematic, which is, you know, how do you make the iron ore industry greener?

“In China at the moment, for example, Beijing has got these sort of these opposing targets. One of them is post-COVID infrastructure spending. The second thing is, hey, we’ve got the Winter Olympics coming up and in February in Beijing and we want blue skies, so let’s cut back on steel production.

“Now, the way that mills can actually sort of meet those two seemingly incompatible goals is actually use high grade ore because you can then make more product and you produce less waste and less emissions.

“And going forward, carbon intensity and emissions intensity of the industry is going to be a much bigger issue than it is today.

“You’re already seeing it today and that should drive premiums for high grade ore, especially high grade direct ship ore that will go straight into the blast furnace without any need to sinter which is obviously a horrific environmental process.

“So the higher 60% grades we hope to produce absolutely will be in demand.”

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.