Great Sprott! Five reasons to be bullish on uranium from the famous mining oracles

Pic: John B R Davies/Moment via Getty Images

- Uranium spot prices have risen beyond US$56/lb this year

- Sprott says the “stars are aligning” for uranium and nuclear energy

- Here are five reasons the investment manager sees yellowcake getting tastier

North American investment manager Sprott has its roots as a precious metals company, famed for its founder Eric Sprott’s bet on bullion as the world burned around the Global Financial Crisis.

A good bet it was indeed. Since 2007 gold is up over 11% a year, including gains of more than 25% across both the GFC and Covid-19 pandemic.

But Sprott has hit the headlines in recent years for a similar counter-cyclical bet, this time on the promise of a major revival in nuclear power and uranium.

Front-running the market, it launched a physical uranium trust when spot prices were in the toilet a few years ago, sending lightly traded spot on a surge in 2021 when it entered with the subtlety of a Yankee industrialist buying up the main strip of a southern town in a 1950s Western.

Prices have risen solidly so far this year, lifting above US$56/lb, with ceilings in term contracts moving progressively higher.

All the while the bull case for uranium has picked up, with restarting producers seeing strong contracting demand and the incentive price for new producers rising into the US$80/lb range.

READ: ‘Inundated with offers’: Conservative Boss calls imminent uranium bull market

The spot price for uranium oxide — aka yellowcake — is up 16.35% YTD and 20% over a three-year horizon.

Uranium equities have lagged, up 9.11% this year but 37% in the past three summers, while U3O8 juniors are down 1.92% YTD, but up 36.86% in the past three years, an index maintained by Sprott itself.

Don’t take our word for it though. Sprott came out last week with a new research report on why the “stars are aligning” for uranium and nuclear energy.

Here are five key takeaways from the note.

Nuclear build programs keep expanding

Uranium prices have been resilient when compared to the broader commodities index, up almost 120% over the past five years in comparison to a 25.7% lift for other metals, which have also slipped 4.85% this year.

While demand is uncertain in many commodity classes, Sprott has pointed to a number of new nuclear developments as evidence of positive movements in the end user market for yellowcake.

In the US the first newly constructed nuclear unit in THREE DECADES, Georgia Power’s Vogtle Unit 3, has entered commmercial operation. A fourth unit will enter operations either side of the new year, making it what Sprott refers to as the “largest generator of clean energy in the US”.

That build is dwarfed in China, where its State Council recently approved the construction of six units worth US$17 billion. It could propel China above France to become the country with the second most nuclear generators outside the States.

Japan just restarted its 11th reactor since the reopening of a fleet shut after the Fukushima disaster in 2011, South Korea is considering new plants and said earlier this year it wanted to ramp up nuclear as a share of power generation from 26% in 2021 to 32.4% in 2030 and 34.6% in 2036.

The UK wants to add another 24GW of capacity by 2050, while the Ontario Government has asked for a feasibility assessment from Bruce Power on adding 4.8GW of generating capacity to make it the largest nuclear site in the world.

Shares in the West’s top uranium miner are at 12-year highs

Uranium miners have caught up and recently started to outperform the price, something Sprott says was correcting a previous market dislocation.

Cameco, the biggest publicly traded uranium company and one of two market behemoths alongside Kazakhstan’s Kazatomprom, the world’s largest uranium miner, is up to a 12-year share price high.

“Cameco performed well into month end, ahead of its earnings call on August 2, 2023, which delivered mixed results,” Sprott said.

“On the one hand, Q2 2023 results were below the market’s expectations, but the forward guidance continued to improve.

“Cameco’s revenue outlook for 2023 was increased by 7% to between $2.4 – $2.5 billion on the back of higher forecasted sales (not production).

“The company also increased its long-term contracting commitments

requiring annual delivery of an average of 28 million pounds over the next five years (compared to 26 million the prior quarter).”

Uranium contracting is poised to hit a new decade high

On that note, Sprott says uranium contracting is accelerating, with 118Mlb contracted so far in 2023.

That’s already closing in on the 125Mlb contracted in 2022, the highest in a decade.

“We believe it is only a matter of time before utilities return to replacement rate purchasing, signifying a greater potential of future demand for uranium,” Sprott says.

That’s triggered a supply response. Boss Energy (ASX:BOE) is rebuilding the Honeymoon mine in South Australia, while Paladin Energy (ASX:PDN) is reviving the Langer Heinrich mine in Namibia and Cameco restarted its McArthur River mine in Canada, where 2024 production guidance was ramped up from an initial 15Mlb to 18Mlb in February.

Sprott says even these restarts won’t be enough to cater to demand.

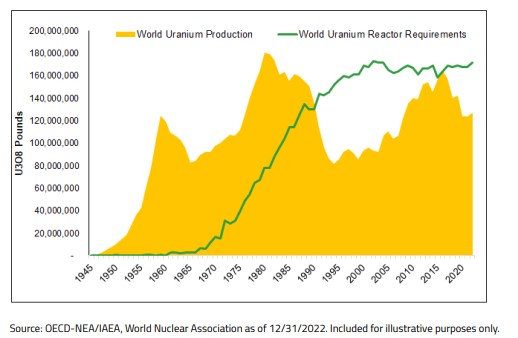

“Although this represents the largest uranium mine restart, global uranium mine production is still well short of the world’s uranium reactor requirements,” they said.

“This deficit further underscores the need for further restarts and new mines in development.”

Uranium supply in Third World countries is vulnerable

Sure you’ve heard Nigeria, home of the Super Falcons and Super Eagles. But have you heard of Niger?

If it rings a bell that’s cause it’s the latest country to fall prey to a Coup d’Etat over in West Africa, where President Mohamed Bazoum was detained on July 26 and replaced by a junta with a decidedly anti-French bent.

“The junta has escalated anti-French rhetoric and allegedly said it was suspending exports of uranium to France. Niger is the seventh-largest producing country of uranium but delivered 25% of the EU’s 2022 supplies,” Sprott noted.

“Niger and France are also directly linked through Orano SA (Orano). Orano is a French-headquartered private uranium mining company, with the second-largest uranium production of any company in 2022, and a large uranium mine in Niger.”

Orano’s operations are continuing, but other public listed companies operating there have seen their share price smashed.

“In terms of publicly listed companies, both Global Atomic Corporation and GoviEx Uranium Inc. have interests in Niger and have also stated that normal business is being conducted,” Sprott noted.

“Investor perception of the event has told a different story, with Global Atomic’s stock price plummeting, potentially signaling an expectation of a delay in the start of the new mine in Niger, Dasa.

“GoviEx Uranium has also sold off, albeit less precipitously.

“This situation highlights the vulnerabilities of the uranium supply chain due to its concentrated production and may result in uranium price spikes.”

It’s worth noting that 44% of uranium supply comes from just one country, Kazakhstan, where supply could be impacted due to its supply chain links to Russia.

It’s not only in the developing world where some project delays are being seen. Peninsula Energy (ASX:PEN) recently had to postpone the restart of its Lance ISR project in Wyoming after Uranium Energy Corp cancelled a processing agreement.

The US needs new supply to break its reliance on Russia

Russia’s outsized role in the nuclear fuel supply chain means the risk of a bifurcated market is fast growing in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine last year.

The US has by far the largest fleet of nuclear reactors worldwide and needs 50Mlb of uranium to operate each year.

But they are largely depending on imports to operate.

Efforts are in train for the US to exclude Russian uranium from the world’s biggest end market, having last year accounted for around 12% of the uranium purchased by American utilities.

“The U.S. Senate (Senate) overwhelmingly passed the Nuclear Fuel Security Act. This bipartisan legislation directs the Department of Energy (DOE) to increase domestic nuclear fuel production to ensure a disruption in Russian uranium supply would not affect its operating fleet and the future deployment of advanced reactors,” Sprott noted.

“The Nuclear Security Act follows the passing of the Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act and the Accelerating Deployment of Versatile, Advanced Nuclear for Clean Energy (ADVANCE) Act and may indicate that it may be only a matter of time before the Russian nuclear fuel supply chain is cut off.”

That leaves a cavernous hole which will need to be fed from other sources.

Uranium share prices today:

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.