Five stats that illustrate the new mining boom… and why it could keep booming

Even a child could see it. Picture: Getty Images

- Hedley Widdup’s ‘mining clock’ is stuck on 11pm as investments canters along

- Mining tenements and applications now cover 45% of WA’s land mass

- 105 mining IPOs hit the ASX last year, largest number of resources floats since 2007

The pace of the mining industry has been extraordinary since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Initially viewed as the trigger for a major global recession, the global crisis instead spurred a splurge from investors in equities leading to a wave of liquidity heading first into gold and the big miners and then into small caps.

Hedley Widdup from Lion Selection Group (ASX:LSX) says the mining investment firm’s patented ‘mining clock’ has been set to 11 o’clock for some time now.

“We’ve had that at 11 o’clock for a little while now, which suggests that midnight is coming around and there’s a sense of inevitability about it, which is that liquidity builds up and up and up and up and up in the space,” he said.

“And that can either be for a mining-intrinsic reason or it can be overlain as it is at the moment by equity market conditions, which make equity investors willing to take risks and go down into smaller companies which have commodity style risks over the top of them as well, like explorers.”

Some in the resources industry treat the word ‘Boom’ with the kind of fear the skeletal characters of J.K. Rowling’s Potterverse have of the word ‘Voldemort’, with its association with Cashed-Up Bogans, corpulent billionaires, extravagance, wastefulness and the painful bust that followed the end of the last cycle in 2015.

But evidence has been building for a while now that we are in the midst of another mining boom.

The question is …

How close are we to the top?

Widdup says while the short hand of the clock may be pointing to 11, it could stay there for years to come.

“I was speaking to people in Sydney last week, they were pretty convinced that it was actually a couple of weeks ago and we’re just tumbling down the other side now,” he mused.

“And likewise 11 o’clock in previous cycles has been measured in years.

“The clock certainly doesn’t go from, you know, one to two to three all the way around to 12 at a rhythmical rate, it progresses as liquidity permits, and I think all we can really say with a great deal of confidence is that with 2021 in the rearview mirror there was an awful lot of liquidity that flowed into the space.”

Stocks have retreated in recent weeks, impacted by a slowdown in metals demand from Covid lockdowns in China, jitters from the Russian war in Ukraine, volatile bond yields, runaway inflation and rate rises among other things.

Outside resources, the tech heavy NASDAQ recorded its worst monthly decline since 2008 in April, falling 13.3% to enter its first bear market since hitting an all time high in November.

The ASX 200 is down 8.55% year to date, ASX 200 Resources is better at 0.11% down, and All Ordinaries Gold has slipped 6.59%. Meanwhile the ASX Small Resources Index is still up around 15% over the past 12 months but ~12% off over the last 30 days.

“We’ve definitely had a pullback I think aligned with the equity market and the conflict which exists in the world at the moment, which is unusual, and certainly tempts people to rethink the kind of risks they’re taking on their investments,” Widdup says.

“And there could be a catalyst that within all of that brings about an equity market correction, which will definitely affect liquidity in the mining space.

“But I don’t want to say that it’s going to happen tomorrow because the Chicken Little approach just makes you sound like a conspiracy theorist.”

Other market watchers, like Argonaut stockbroking boss Eddie Rigg, have suggested the boom could be prolonged by the desperate need for critical minerals and commodities like nickel, rare earths, copper, iron ore, lithium and steel to feed the energy transition.

Widdup says he is a believer in the thematic but warned even fundamentals struggle against the tide of a falling equity market.

“It’s always different this time and one characteristic of a hot market is that there’s a lot of people who look for a justification as to why it is that the market is different, to sort of convince themselves or reassure themselves that it’s going to go on for longer than objectivity might suggest,” he suggested.

“So I don’t want to call out the proponents of that and say that that’s ridiculous because I buy the phenomenon. I really do think that the proliferation of EVs, batteries, storage of energy et cetera is something which is going to result in a structural shift in demand for metals which are most exposed to that longer term.

“But it doesn’t prevent cycles from taking place.

“A great example of that might be in 2006 and 2007, there was an expression ‘stronger for longer’ and that was applied to things like copper and iron ore and China needed more iron ore than was available in order to continue building its economy. For that reason, iron ore was going to go on right through whatever happened.

“But it couldn’t compete with the global financial crisis when it happened.”

For now though, liquidity and activity in the mining industry remains around record levels. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, mining equities globally hit a 10-year high market cap of US$2.34 trillion in March.

Here at Stockhead we’ve chosen five stats that illustrate why we are in the midst of the mining boom.

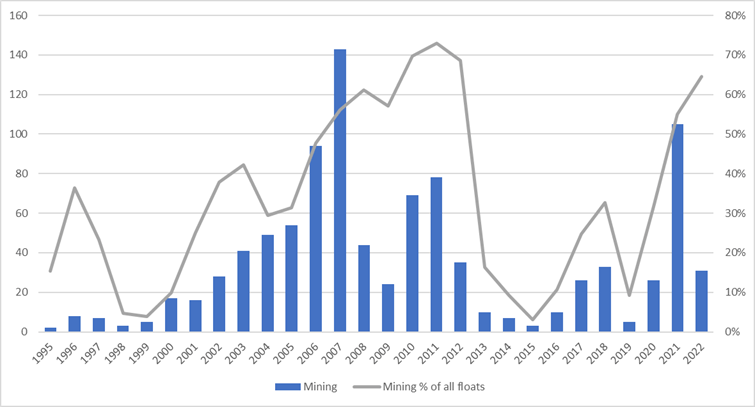

IPOs hit cyclical highs last year

There were 105 mining IPOs to hit the boards of the ASX last year, the largest number of resources floats since 2007.

So far 31 resources IPOs have listed in 2022, already eclipsing any full year total since 2011 aside from 2021, 2018 and 2012 despite promoters saying the market has been getting tougher.

Mining floats as a percentage of all IPOs have also risen to ~65%, levels not seen for a decade.

“Seeing a big jump up there is a strong signal to me that we’re in those years, which are in-between 9 and 12,” Widdup said.

Another notable event was the more than $500 million listing of copper miner 29Metals (ASX:29M) last year.

“If it’s hundreds of millions of dollars that you want to raise in fresh cash either to sell down or to generate a funding to make a transformative acquisition or investment in the company, that liquidity just does not exist,” Widdup said.

“And to list big companies you need to see it being 10 o’clock, usually 11 o’clock.

“So seeing that come to market was one of the things which made us think that we’re rounding off towards that top part.”

Mining tenements and applications now cover 45% of WA’s land mass

The hottest mining jurisdiction out is still Western Australia.

While it might be tempting to choose oft-quoted numbers like exploration expenditure and POW (program of work) applications, we’re going for a bit of good ol’ fashioned pegging.

That’s right, the number of stakes stamped into the ground by prospectors, miners, explorers and realtors alike in the past two years has absolutely exploded.

Part of that may be due to exploration success stories like Chalice Mining’s (ASX:CHN) Julimar discovery and De Grey’s (ASX:DEG) Hemi gold find.

But it also reflects increased liquidity across the sector. Holding tenements costs money in application fees, rentals and exploration expenditure, which is required under the WA Mining Act’s Use It Or Lose It principle, so you need cash to burn just to sit on the ground, let alone explore or dig it up.

According to figures supplied to us by the Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety, back in January 2020 around 20% of WA’s land mass was covered in granted mining tenements, with 9% under application.

Today 27% has been granted with a further 18% under application, meaning up to 45% of the State could hypothetically be open to mining or exploration.

In a downturn those numbers drop as miners fall under financial stress because of the significant holding costs of unproductive prospecting, exploration and mining leases.

The huge rise in tenement rental payments is being put into a range of programs including a $12 million passive seismic survey to uncover potential deep critical mineral targets.

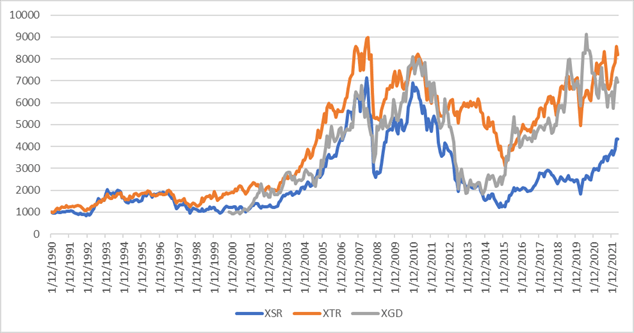

The Small Resources Index has done some major catching up on the big boys

This is where the battery metals aspect of the current cycle has really become apparent.

Late in the cycle, Widdup says, cash tends to flow from large cap to smaller miners as investors chase bigger returns from more leveraged opportunities.

The ASX Small Resources Index (ASX:XSR) has outpaced the ASX 100 Resources Index (ASX:XTR) in the past two years during a recovery for the mining industry initially led by gold stocks.

Widdup says the leading role smaller mining companies have taken in battery metal lithium, the fastest rising commodity in the past year, has been a big factor.

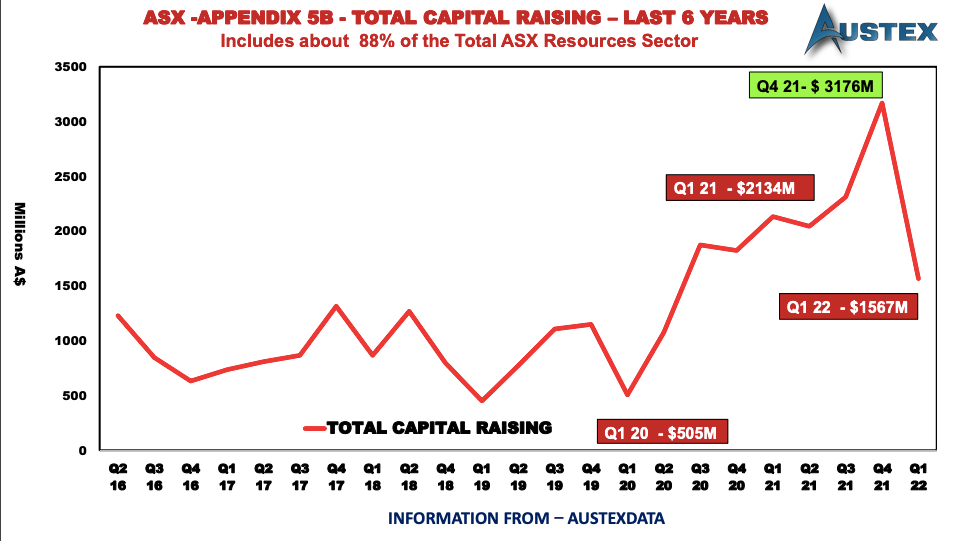

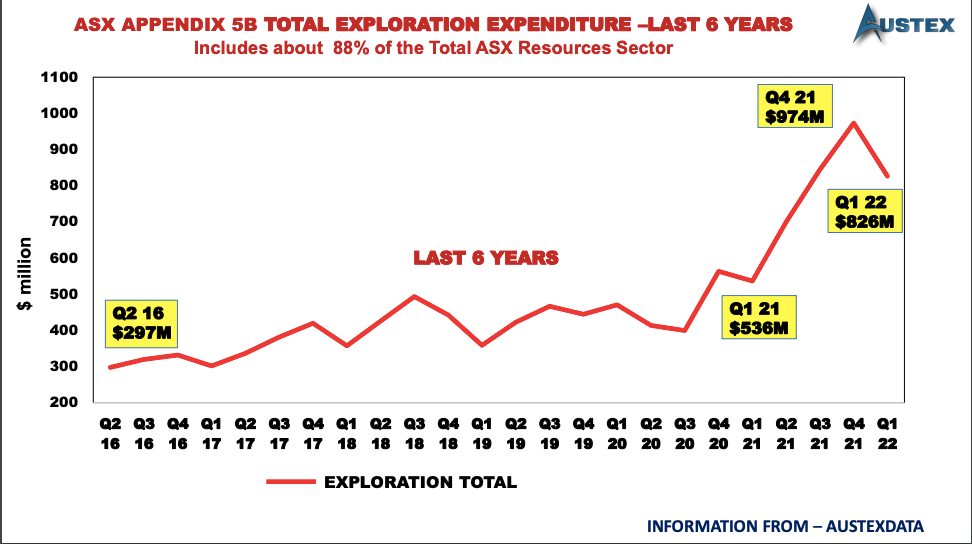

Explorer raisings soared in 2021

Rob Murdoch, principal consultant and executive director at Austex Resource Opportunities , says the amount raised by companies making quarterly 5B reports (required for mining and oil and gas exploration stocks) has surged since Covid.

According to figures compiled by Murdoch for Austex’s quarterly report, 5B reporting companies comprising 88% of the resources firms listed on the ASX raised an epic $3.176 billion in the December quarter of last year, 529% higher than the $505 million raised in the first quarter of 2020.

That dropped to $1.567 billion in the first quarter of 2022, but remains well above pre-Covid levels, Murdoch notes.

Companies reporting 5Bs have grown by 15% over the past 12 months, rising to 836 from a low of 726 in the third quarter of 2020, climbing above Q1 2016 levels (823) for the first time.

According to Austex, exploration expenditure across 5B reporters hit $974 million in the fourth quarter of 2021 and $826m in the first quarter of 2022, up from $536m in Q12021 and just $297m in the second quarter of 2016.

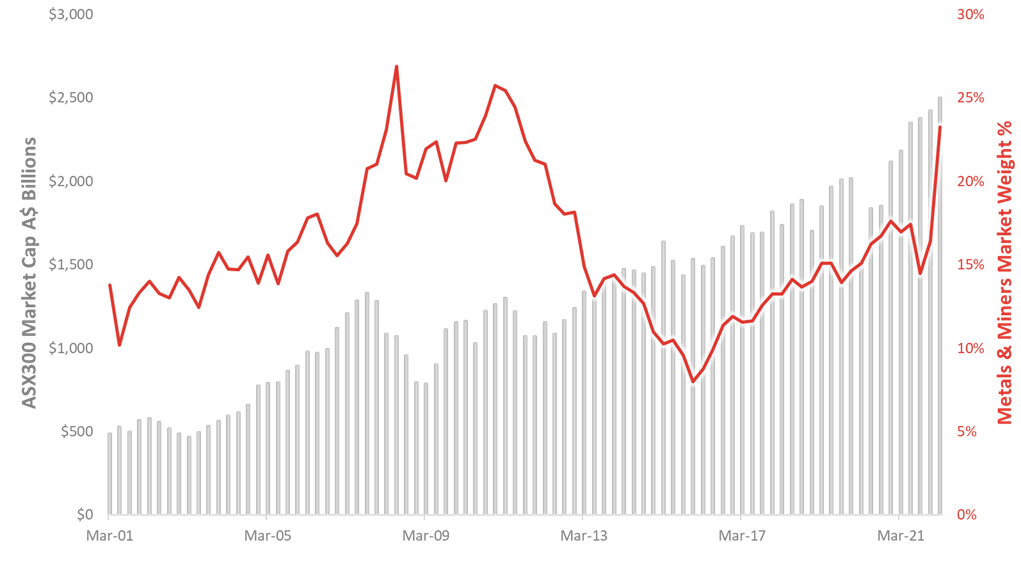

Miners have stolen their largest share of the ASX 300 since 2006

Back in 2015 as benchmark 62% iron ore prices slid to just US$38/t, miners hit an all time low 8% composition of the ASX 300, one of the key indexes for institutional investors and super funds.

They’re now heading back towards the 25% mark, levels not seen since 2011. Although the inclusion of BHP’s (ASX:BHP) previously separated British business after the collapse of its dual company structure this year has had a big impact.

(It could be said that in itself is evidence of the boom, with BHP’s record profits, share price and cash generation helping it convince shareholders to back the move to make major M&A easier down the track.)

Widdup says the market weight of financials to miners has shown an inverse relationship through the cycles, reflecting how investors shift from safer to more risky investments in an upswing.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.