Copper boom brings Alma Metals to life in bid to develop Queensland porphyry

Pic: Tyler Stableford / Stone via Getty Images

The positive outlook for copper prices as the world begins the long but accelerating transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy will unlock deposits previously thought uneconomic.

The headline that the world needs more copper and will be willing to pay for it has seen a number of companies reassess or invest in established copper deposits that have gone undeveloped for a variety of reasons.

Alma Metals (ASX:ALM) is one of the junior companies that has made that pivot in recent months, shifting its focus from African energy assets under its previous guise as African Energy Resources.

Alma now has a fresh focus of copper-gold assets in Australia and in a standout feature for a junior explorer with a market cap of a little over $20 million already has a massive JORC compliant porphyry deposit in its hands.

Briggs brings the heat in strong copper environment

It has an option to earn-in for 70% of the 241km2 Briggs Copper Project 50km inland of the strategically significant Queensland port town of Gladstone, which has long sat in the portfolio of Canterbury Resources.

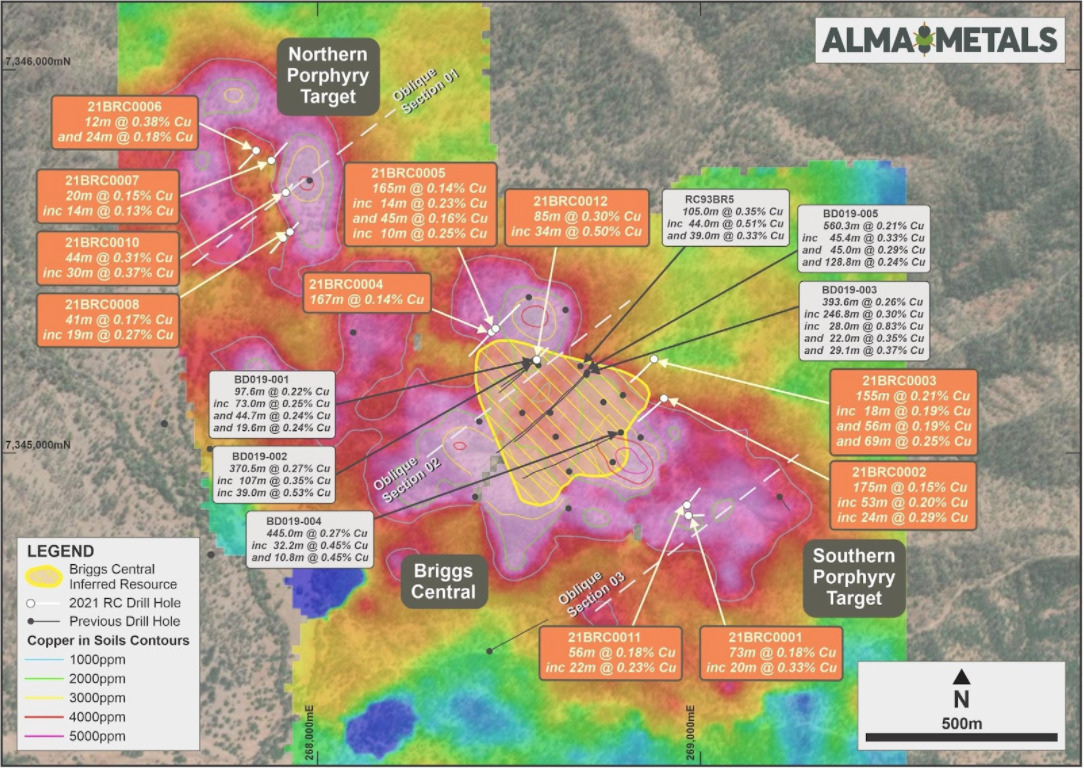

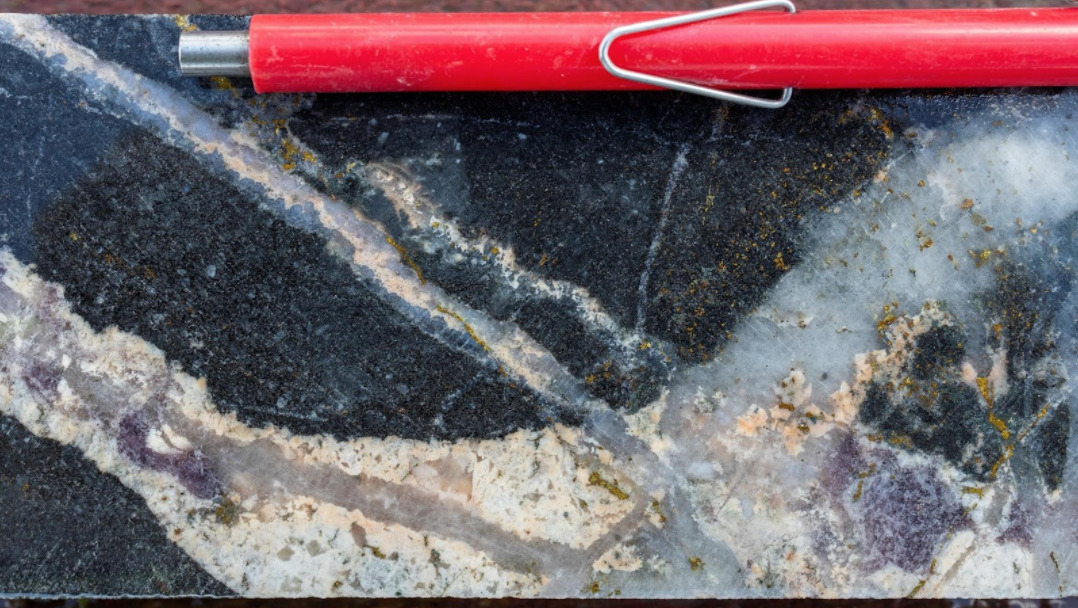

Comprising the Briggs, Mannersly and Fig Tree Hill tenements, Briggs already contains a porphyry copper resource of 143Mt at 0.29% copper and early investigations suggest that is likely to grow further, with Alma striking copper and molybdenum mineralisation 750m from the known resource.

In a world of US$10,000/t copper, and potentially rising, Briggs could be a proverbial gold mine. Alma CEO and executive director Frazer Tabeart says the company has picked the ideal time to unearth its rich copper potential.

“The fundamental difference between say now and five years ago is five years ago the copper price was substantially lower,” he explains.

“And at those lower copper prices, 0.3% copper in the ground meant the in situ value of mineralisation was probably in the order of US$15-20 a tonne.

“So, unless you had massive scale, your processing and mining costs were going to be well over US$10 a tonne, and there wasn’t enough margin in there for it to be viable.”

At current prices of around US$10,000/t, near all-time highs, that picture looks a lot different.

“If you go to $10,000 at 0.3% copper, that’s an in-situ value of $30/t. And if your all-in mining, processing, and other costs are of the order of $10 a tonne, then you’ve got a $20 margin, which is capable of supporting repayment of a capital investment, as well as generating a strong profit over a long period of time because you’re talking a big scale project,” Tabeart says.

World needs more copper and now

Driving the fundamental shift in demand for the red metal, often known as Dr Copper for how it can be seen to diagnose the health of the global economy, is the electrification and de-carbonisation narrative.

The weight of copper in an electric vehicle is a multitude higher than a conventional internal combustion engine.

The installation of new renewable energy will also require incredible amounts of cabling and copper remains the best conductor of electricity outside prohibitively rare and expensive precious metals like gold and silver.

“People are going to use electricity as a primary energy source where they can and all of that needs copper,” Tabeart says.

“Every electric vehicle uses two or three times the amount of copper than a normal internal combustion engine vehicle, all the wiring around solar panels, wind turbines etc. it’s all copper.

“We think that the demand for copper has good, sustainable long-term growth in it.”

New undeveloped projects are also advantaged by the declining grade and output of the world’s largest copper mines at a time when production needs to increase to satiate demand.

“When you look at the grades of the world’s biggest copper deposits, they’re all starting to drop,” Tabeart said.

“If you looked at the world’s 10 or so biggest copper deposits – with one notable exception in the Congo – the grades are dropping substantially below 1% for the first time in over a century.

“And that means there’s going to be less metal, or more tonnes have to be moved, so costs will go up as a result of that.”

Aussies do it better

Unlike Alma’s projects, which are all based in Australia, many of these mega mines are in South America and specifically Chile and Peru, where new nationalistic tax regimes will eat at the margins, increase costs and potentially disincentivise both investments in new mines and expansions of old ones.

That is expected to underpin higher prices for projects like Alma’s.

“There’s a lot of debate going on in South America at the moment on royalty rates, and that’s going to definitely have an impact on copper prices,” Tabeart said.

“So, we think if you’ve got a low-grade large deposit in a stable fiscal jurisdiction with good infrastructure, good metallurgy, low stripping ratios, 0.3% copper at US$10,000 … it almost certainly will work, subject to doing your feasibility studies.

“And we think there’s probably upside potential on the copper price, much more so than long-term downside risk.”

The location of the Briggs project in the predictable and mining friendly Queensland jurisdiction, in an area of the state being prioritised for green industrial development bodes well.

“Where that project is in Queensland, we think is going to tick all of the boxes,” Tabeart said.

“We know the mineralisation is at surface, so the strip ratios are likely to be low.

“We know there’s low-cost power there, we are close to deep water ports, we’re close to railway lines so transport to port is not going to be an issue. And some very early metallurgy testing that was done by Canterbury indicated that the metallurgy looks very simple.”

Briggs a grower

To exercise the option at Briggs, Alma has to spend $750,000 in initial exploration before July 31 this year.

It can then earn a 70% stake by spending $15.25m over nine years in a staged earn-in, starting with $2.25m to earn a 30% interest within the first two years once the option is exercised.

Results from RC drilling to date funded by Alma suggest there remains plenty of upside to the resource, which already contains around 414,700t of in situ copper metal.

“The focus is mostly going to be on drilling to increase the size of the resource. So, the current resource has a surface footprint of about 450m by 500m,” Tabeart said.

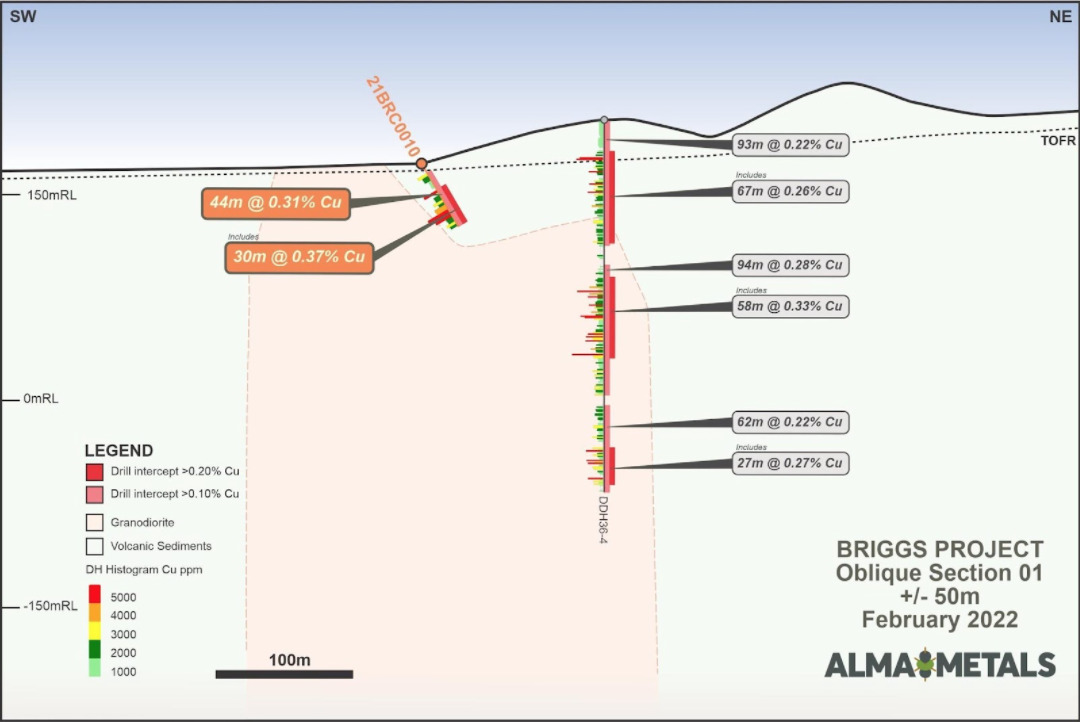

“The very recent drilling campaign that we did, which was just shallow RC holes, has discovered mineralisation up to 750m along strike in either direction.

“We’ve got a system where we see drill intersections at 0.25-0.35% copper now over more than 1500m. Those are within a surface geochemical anomaly, which is over 2000 metres long and there’s just very, very little drilling in that area.”

Alma expects to exercise its option well before the deadline in the next couple of weeks and be back drilling by early May. Within the next 6-9 months Tabeart expects that drilling along with more metallurgical test work will feed into a substantial resource upgrade and scoping study.

No one-trick pony

But Alma has hardly put its eggs in one basket with Briggs.

It also has two projects in WA, exciting greenfields exploration initiatives in WA’s South West and Kimberley regions.

The Sunnyside-Mayanup, Tarin Rock and Kondinin projects in the South West are on its books, five tenements across the South-West of WA, a region newly regarded as an exploration hotspot since the discovery of the Julimar nickel-copper-PGE orebody by Chalice (ASX:CHN) in 2020.

Those leases are considered to be prospective for both intrusion related orogenic gold systems and large copper porphyry deposits like Briggs and the Caravel project near Calingiri to the north.

Alma is starting off with surface geochemistry to assess the size of the prize.

A second greenfields project, the East Kimberley project, includes the Cambridge Gulf and Menuair Dome projects near Wyndham which remain under application.

There Alma is seeking a different style of copper mineralisation entirely.

“We’re searching there for stratiform copper deposits very similar to those in the Central African copper belt,” Tabeart said.

“They tend to be much, much higher grade and can occur over large (areas).

“One of the world’s best new copper projects is one in the in the DRC that’s a joint venture between one of Robert Friedland’s companies (Ivanhoe Mines) and a Chinese group (Zijin Mining) and the Govt of the DRC. I think … the first 10 years or so is over 5% copper so they can be extremely rich deposits.

“And the East Kimberley seems to have the right geology.”

Alma is in talks with traditional owner groups to secure access agreements covering the target areas.

“It’s a bit more at the grassroots end than we would normally go for but the size of the potential prize there is so good it’s worth doing,” Tabeart said.

“There’s a lot of outcrop there, it’s something that’s relatively easy to assess on a first-pass basis using low-impact helicopter supported stream sediment sampling. If there’s a decent scale deposit there we’ll pick it up fairly early and get onto it.”

Experience counts

When it comes to the porphyry copper game Alma has numbers on the board.

It already owns a ~$5m stake in Caravel Minerals (ASX:CVV), the owner of the Calingiri project in WA which Caravel aims to have a PFS out on in the March quarter.

“So through that relationship we understood a little bit about what 0.3% copper really means in the days of US$10,000 a tonne copper,” Tabeart said.

“There’s a lot of public information from Caravel that will help us guide our decision making that is very applicable, because the deposits appear to be so similar (Calingiri and Briggs).”

Caravel’s top shareholder is Alasdair Cooke, the executive chairman of Alma whose geology career includes 30 years in the resource exploration and mining industry with BHP, Albidon, Mirabella Nickel, Sally Malay Mining (Panoramic Resources) and Exco Resources, which happened to sell the Cloncurry copper mine for $175 million to XStrata (now Glencore) to add to the famous Ernest Henry copper operations.

Tabeart for his part was a principal geoscientist at Western Mining Corporation in its exploration division, spent years working and living in the Philippines and had a focus on porphyry copper exploration, visiting more than 30 world class porphyry copper mines.

“I’ve seen the spectrum of what these things look like, I’ve evaluated them on an almost 12-month sabbatical within Western Mining from deposit scale all the way up to global scale,” he said.

“So I’ve got a very good understanding of the processes that operate to form those deposits, and then what they look like in the field, and a good understanding of the variability between and within them.

“That skill set is very valuable when you’re drilling one of these opportunities, because they can have complex geology that can be a distraction.”

Targeting a global market

That experience leaves Alma well placed to hone in on the emerging copper growth story being seen around the world.

“Some of the other more boutique battery metals, battery technology is going to change, they’re going to change quickly,” he said.

“There’s no guarantee that all of those other battery metals are actually going to be in high demand in three- or four-years’ time.

“The global copper business is 24-25Mt a year of mined metal and likely to increase to 30-35Mt over the next 10 to 15 years. It’s a big and well-established market.

“I always prefer to be in a big market rather than in a boutique market that suddenly changes on you, and we’ve got a project that’s largely flown under the radar in Queensland and looks to have huge upside.”

This article was developed in collaboration with Alma Metals, a Stockhead advertiser at the time of publishing.

This article does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.