Coal demand still has legs, says the IEA

Pic: Schroptschop / E+ via Getty Images

Australian thermal coal producers and explorers could still have several years of strong demand to look forward to if the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) outlook for the fossil fuel is anything to go by.

Thermal coal is the kind used in power stations, while higher quality metallurgical or coking coal is used in steel manufacture.

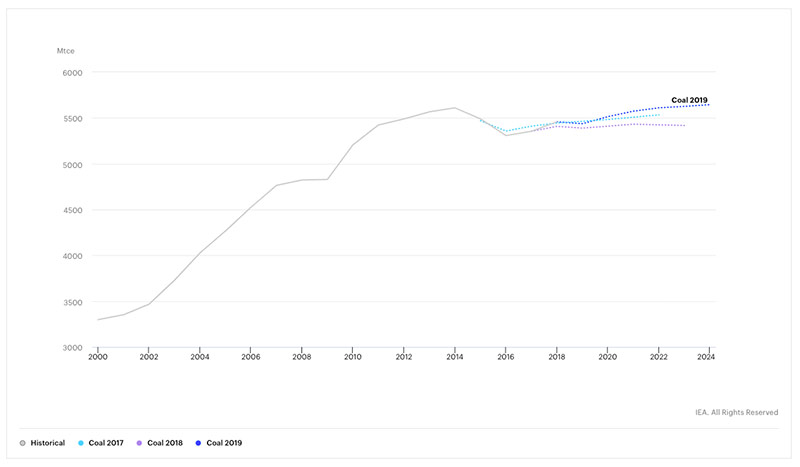

In its latest Coal 2019 report, the IEA found that coal maintained its position as the largest source of electricity in the world with a 38 per cent share in 2018 while coal demand increased by 1.1 per cent in the same year.

This is due to strong demand from China, Indian and other Asian economies that more than offset falling demand in Europe and North America.

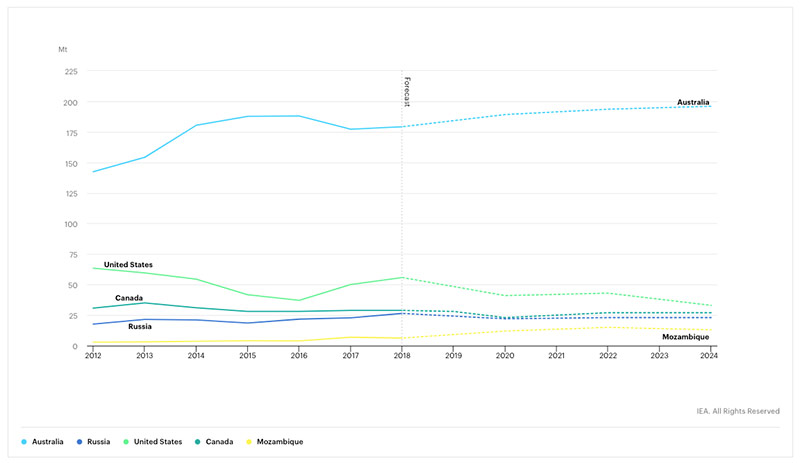

Coal production rose 3.3 per cent to meet this demand with India, Indonesia and Russia – three of the world’s largest coal producing countries – producing their largest outputs ever.

Even Australia recorded coal export revenues of $US67 billion, making it the country’s top commodity export.

China remains the world’s largest coal producer and consumer due to stronger than expected electricity consumption and infrastructure development over the last couple of years.

Coal power generation is expected to continue growing, albeit at a slowing rate.

READ: Is thermal coal an unbackable favourite, or just unbankable?

However, coal use in the residential, small industrial sectors, and heavy industry will fall.

Overall, the IEA expects Chinese coal demand to plateau by 2022 before declining slowly. It also noted that future coal demand could be affected by the government’s economic growth objectives as well as its policies on nuclear power, wind and solar.

The rapid development of Asia’s other giant, India, is also expected to provide support for coal demand.

While power generation from renewables is forecast to grow strongly, the rapidly growing energy demand means that India’s coal power generation is expected to increase by 4.6 per cent per year through to 2024.

Pakistan has commissioned over 4 gigawatts (GW) of new coal power plants with similar capacity under construction while Bangladesh is about to commission the first unit of the 10GW it has in the pipeline.

Additionally, coal demand in Southeast Asia is expected to grow by more than 5 per cent per annum through 2024 due to strong economic growth in Vietnam and Indonesia.

Conversely, the ready availability of cheap and cleaner natural gas along with pressure to reduce air pollution is expected to reduce coal power generation in Europe by more than 5 per cent per year through 2024.

Coal’s future in the US is more dire with the shale gas boom causing coal’s share in electricity supply to decline from as high as 50 per cent in 2007 to 28 per cent in 2018 and 21 per cent in 2024.

What does this mean for the Australian coal sector?

The continued demand for coal is likely to keep coal exports running at current levels, with the Minerals Council of Australia noting that about 203 million tonnes of thermal coal and 179 million tonnes of metallurgical coal were exported in 2018.

It added that the high-energy, low-ash characteristics of Australian coal could reduce emissions when compared to lower quality coal from other exporters.

MCA chief executive officer Tania Constable told Stockhead that the IEA’s forecast was good news for regional communities, jobs and Australia’s economy.

“If Australia lifts its game so new coal mines are approved more quickly, our nation will be able to maintain its edge as a reliable supplier of top-quality coal to the world – reducing emissions compared to the lesser-quality coal produced by competitors,” she said.

“Importantly, the IEA backs efforts to boost the use of carbon capture, utilisation and storage as a viable path to long-term large-scale emissions reduction so nations can continue to use coal for reliable, affordable power while reducing the impact of its use on the environment.”

However, a growing number of Australian financial institutions have put in place policies that restrict their exposure to thermal coal mines and power plants, which could make it harder for new mines to be developed.

This shift could actually mean that small projects, which rely more on private funding, could actually have an easier time securing financing instead.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.