China’s push for more nickel in batteries slightly delayed, but it will come

The lower cobalt price has delayed slightly China’s push towards more nickel and less cobalt in its batteries – but fear not, the switch in chemistries is still on the agenda.

Right now, most batteries use the NCM 622 chemistry, which comprises 60 per cent nickel and 20 per cent each cobalt and manganese.

But for a while now the plan has been to switch to a chemistry make-up of 80 per cent nickel, 10 per cent cobalt and 10 per cent manganese – also known as NCM 811.

More nickel makes batteries cheaper and longer lasting because it can store and produce more energy.

Cobalt is one of the more expensive components of a lithium-ion battery.

It is also plagued with supply issues given 60 per cent comes from the Congo, which has been blacklisted by end-users over ethical issues such as the use of child labour to mine the commodity.

Some 98 per cent of the world’s cobalt is also the by-product of nickel and copper production, meaning there isn’t a great deal of primary production to help meet demand.

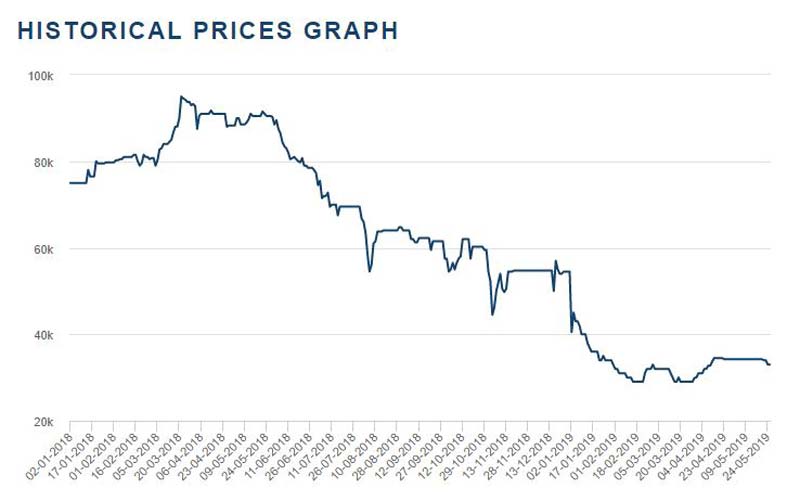

However, since the price hit a new record of $US95,000 a tonne in March last year it has plummeted by over 65 per cent to $US33,000 a tonne.

“The long-term trend to reduce cobalt remains, and the push to NCM 811 continues, but this is challenging on safety and lifecycle issues,” Benchmark Mineral Intelligence cobalt analyst Caspar Rawles said.

“In addition to the engineering challenges around using NCM 811, current cobalt prices and reduced subsidy policies in China have lessened the drive from downstream OEM’s to use the more nickel rich version of NCM.”

While the NCM 811 chemistry is already available for cylindrical cells, according to Benchmark, most electric car makers prefer pouch or prismatic batteries, which require some development work.

Rawles said China was now more likely to adopt the new chemistry from 2020 onwards and other markets from 2021.

This timeline matches one expert’s predictions that nickel could go for a run next year.

“Commodity recoveries are more demand driven than supply shortfall driven,” Guy Le Page, director and responsible executive at Perth-based financial services provider RM Corporate Finance, told Stockhead this week.

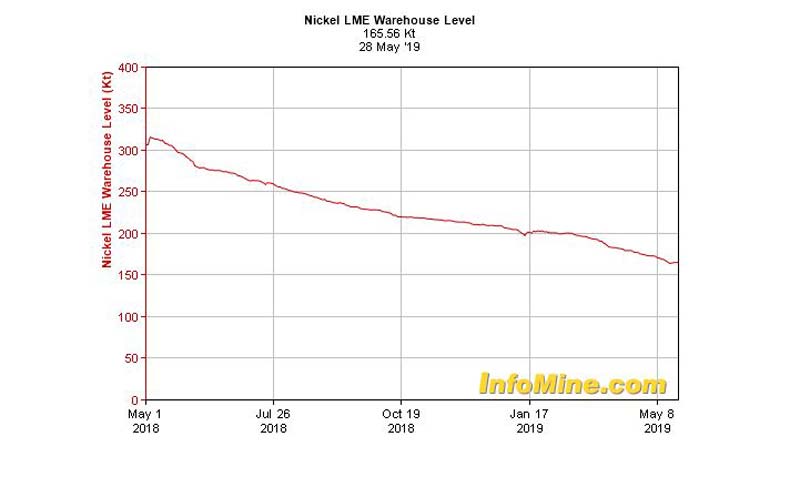

So while stockpiles are at “fairly low levels”, for the base metal to really run, demand needs to head north.

China’s shift to NCM 811 next year could be that catalyst, and nickel prices have already started to turn around.

Since the start of this year, the price has gained over 30 per cent to trade at $US13,605 a tonne in early March.

While it has come back a bit to $US12,230 a tonne, it is still up over 17 per cent.

Wood Mackenzie, although more conservative than others with its estimates, reckons the nickel market is going to need the equivalent of 12 “Ambatovy” mines by 2030.

Ambatovy in Madagascar is one of the world’s largest lateritic nickel mines. At full production its output will be 60,000 tonnes a year, but right now it is producing at 40,000 tonnes a year.

That amounts to 480,000 tonnes of much-needed nickel supply by 2030.

“For the battery sector, the demand for nickel is currently less than 5 per cent but growing up to 35 per cent by 2040,” Angela Durrant, principal analyst metals research at Wood Mackenzie, said an industry event in Perth earlier this year.

“Our projection at this stage is that by 2040, we are looking at about a 1.7-million-tonne requirement to meet our demand projections.”

- Subscribe to our daily newsletter

- Join our small cap Facebook group

- Follow us on Facebook or Twitter

What’s hot in nickel?

Auroch Minerals (ASX:AOU) has decided it’s a good time to get into nickel, revealing this week it will acquire Minotaur Exploration’s (ASX:MEP) WA nickel assets for $1.5m in shares and cash.

Although Auroch is already in base metals, it is the junior’s first foray into nickel.

CEO Aidan Platel said Auroch was “bullish” on nickel.

“We started looking at it in October last year as something we wanted to do,” he told Stockhead. “I think there’s definitely a supply shortage coming on very soon, as early as 2020 and certainly in the next sort of 5-10 years.

“I think now is the time to strike and it certainly still sits in our focus of Australian base metals.”

Minotaur’s Saints and Leinster projects are high-grade nickel sulphide projects, according to Auroch.

Nickel is usually found in two main ore types – sulphide or laterite.

Sulphides are much cheaper and easier to turn into battery grade nickel sulphate than nickel laterites and fetch a higher price.

Auroch is also looking at other potential base metals acquisitions.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.