Cashed-up Alicanto targets ‘massive’ copper-gold system at Wolf Mountain

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

Special Report: A strongly supported $2.5m placement allows Swedish explorer Alicanto to maintain exploration momentum at the new high-grade Wolf Mountain discovery.

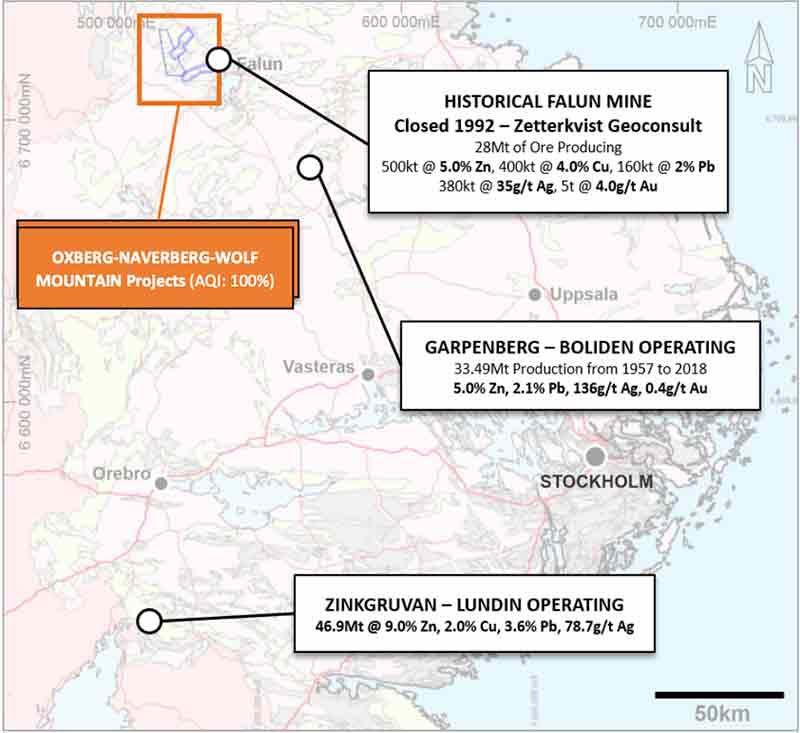

Alicanto (ASX:AQI) is enjoying considerable early success at its projects in the historic mining district of Bergslagen.

The share price, up ~130 per cent in 2020, tells the tale.

This new $2.5m cash injection means the company can maintain this momentum. Wolf Mountain alone, prospective for high-grade and bulk-tonnage copper-gold deposits, is a potential company changer.

“As we peel the onion skin back [at Bergslagen], we are getting super excited by what we are seeing,” Alicanto chief exec Peter George says.

“Everyone I’m talking to — investors and shareholders alike — are wrapped that we have been able to get this money in the kitty.

“We run on the sniff of an oily rag, so the majority of this money will go into the ground.”

A fresh theory pays off

When Alicanto first acquired projects in the mineral-rich Bergslagen district it had some new theories about the kind of geology it was dealing with at Falun.

They believed that some of the traditional understandings of the region were not 100% accurate.

Until recently, a common belief was that the large Garpenberg and Falun mines (below) were standard VMS (Volcanogenic Massive Sulphides).

VMS deposits are rich in base and precious metals like copper, zinc, lead, gold and silver; and because these deposits tend the ‘cluster’ together, VMS camps can often be mined for a very, very long time.

In the late 90s, mine owner Boliden had resigned itself to the fact that the two massive Garpenberg orebodies (the North and South mines), about 8km apart, had been completely mined out over a period of around 800 years.

A lot of drilling had occurred between the two mines over many years, without success.

Boliden signed off on closing the mine when Chief Geologist Erik Lundstam — now with Alicanto — tested a new theory.

“He said — ’we don’t think that these are traditional VMS style deposits, but are what you call Carbonate Replacement Deposits’ (VMS CRD),” George says.

“Unlike traditional VMS, VMS CRD can be ‘tracked’ by following limestone ore horizons for tens or even hundreds of kilometres.

“Erik and his team soon realised that many years of drilling at Garpenberg had never actually intersected this limestone ore horizon and had either stopped short in the hanging wall or footwall.”

Lundstam convinced Boliden management to put a couple of holes into where he believed the limestone ore horizon should be. And the second hole intersected 30m of high-grade VMS. One of Erik’s six major discoveries in Sweden over the last 20 years.

“Over the next few years they managed to delineate 120 million tonnes of ore [at Lappberget and its surrounds] — 30 years’ worth of production — which went a long way to securing the miners future,” George says.

READ: This is why veteran miner Steve Parsons chose to invest in explorer Alicanto

Finding the next Garpenberg and more

This whole region has been misunderstood, says George. On Alicanto’s ground alone there is more than 45km of mostly untested limestone ore horizon that has not been recognised until now.

“We walked the whole thing during the summer of 2019 as part of our reinterpretation of the underlying geology and also drilled into the Lustebo anomaly – all of which confirmed the presence of high grade VMS, but more importantly the sulphides are hosted within a limestone ore horizon,” he says.

“But it gets better! We got to the very western side of our tenement package to a place called Wolf Mountain and found some rocks on surface up to 11.9 per cent copper and 2.9g/t gold.”

Based on the traditional understanding of the area those rocks should not have been there as they were highly altered and did not fit the VMS style of mineralisation.

Alicanto then found a whole bunch of historic workings nearby – located on four separate mineralised trends over 1km in strike “mined by old timers going back into the 1700s”, George says.

“We realised there was a big fault there and a large structurally hosted corridor, anything up to 3.3km wide and 14km long.

“This whole area had never been drilled.”

Alicanto conducted an IP survey which highlighted some very strong High IP – Low Res anomalies and followed up with a maiden drill hole.

That drill hole hit what we believe to be a large disseminated halo sitting around a [higher grade] vein,” George says.

“Consequently, we have steepened the next hole to target that high-grade vein, to get an idea of how big this particular anomaly is.

“But keep in mind that there are at least three more parallel zones that the old boys were mining. We haven’t tested any of these yet.”

Within the next six months Alicanto expects to have a few thousand metres of drilling completed at Wolf Mountain.

“We will soon understand not only what the old boys were chasing 300 years ago; we believe we will also understand the ‘genesis’ of this system,” George says.

“At the moment, every hole is a winner and we are exponentially increasing our understanding of what we are dealing with, how it is formed and where the best place is to drill for economically viable mineralisation”.

NOW WATCH: 90 Seconds With… Peter George, Alicanto Minerals

This story was developed in collaboration with Alicanto, a Stockhead advertiser at the time of publishing.

This story does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.