Australian copper enters new era where scale is king

The king she told you not to worry about. Pic: Getty Images

- While the old adage says ‘grade is king’, that’s not always the case when it comes to copper

- Most copper is produced from low grade but large scale porphyries, largely in South America

- But Australia has the potential to host several of these deposits as future shortages have analysts predicting a sharp run up in copper prices

You’ve no doubt heard the phrase ‘grade is king’, and that’s been the case for a long time when it comes to Australian copper deposits.

Australia pales in comparison to world leaders like Chile and Peru when it comes to production of the red metal, a rare blind spot in a market known for its outright dominance in supplying a swag of metals including iron ore, gold and lithium.

By and large the most successful domestic operations have been high-grade volcanogenic massive sulphide discoveries like Sandfire Resources’ (ASX:SFR) DeGrussa, 29Metals’ (ASX:29M) Golden Grove and Metals Acquisition’s (ASX:MAC) CSA mine in Cobar.

Or they’ve been iron-oxide copper-gold deposits like BHP’s (ASX:BHP) 350,000tpa Copper South Australia assets (including the massive copper, gold and uranium deposit Olympic Dam) or Evolution Mining’s (ASX:EVN) Ernest Henry in Queensland.

But Sandfire’s DeGrussa is a case study for the double-edged sword that is high grade copper mines.

Discovered in a blind drill hole in 2009 and brought to market in 2012 grading upwards of 5% Cu, DeGrussa was enormously profitable and low cost to operate, living a grand life over a decade.

But mines like DeGrussa have obvious pitfalls. Given their relatively short mine lives, they rely on constant exploration success to remain viable, either underneath and adjacent to the deposit or at nearby satellites.

Sandfire, with the help of Kerry Harmanis’ Talisman Mining (ASX:TLM), found just one short-lived add-on called Monty and by the end of DeGrussa’s life had to resort to ‘Hail Mary’ drill holes in the hope of replicating its previous success, never a surefire exploration tactic. A hybrid solar power plant, the first of its kind when installed in 2016, was ripped up and decommissioned just eight years later.

Given the challenges the world faces finding the amount of copper it needs to supply technologies critical to the transition to renewable energy, these kinds of mines can’t be relied on to predictably fill the supply gap.

Porphyry giants

By contrast, the vast bulk of the world’s largest copper mines are actually porphyry in nature, which are lower in grade – often cutting off at grades as low as 0.2% Cu, a fifth of DeGrussa’s.

But they’re high in tonnage and dependable, often having lives that run into the decades and generations on opening, with resource growth from existing deposits historically exceeding that from new discoveries, demonstrating their potential to be expanded over time.

Generally they’re mined in large open pits or via bulk underground methods like block caving, where economies of scale make up for deficits in grade.

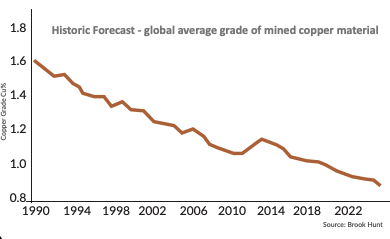

Though some exceptional orebodies run higher the average grade delivered by major producers of all kinds of copper are down from 1.2% to 0.72% in the past decade and reserve grades globally sit at an average of 0.4%.

That’s a function of them ageing and becoming harder to find, but also advancements in mining and processing technology that have opened up previously uneconomic resources. On the most extreme end of the spectrum, Boliden’s long-running Aitik mine in Sweden mines grades of less than 0.2% copper and 0.1g/t gold despite operating through often inhospitable winters.

The idea of pursuing scale over grade is also being seen in M&A, with BHP’s (ASX:BHP) C$4.1bn deal to acquire half of the Filo Del Sol and Josemaria JVs with Lundin Mining netting two assets in Argentina with grades of around 0.3% Cu.

Australian copper monsters

Two of Australia’s top copper producers are also in that vein.

Newmont Corporation (ASX:NEM) last year acquired Newcrest in a multi-billion dollar merger, largely for the purposes of procuring its enormous Cadia-Ridgeway mine in New South Wales near the country town of Orange.

Predominately known as a gold mine, Cadia delivered 597,000oz at costs of just US$45/oz in FY23. But it’s also Australia’s second biggest copper producer behind Olympic Dam, producing almost 100,000t in FY23.

Its head grades run at ~0.8g/t gold and ~0.4% copper, but the massive sprawl of the orebodies at Cadia and the adjacent Ridgeway mean it can be relied on to produce at a consistent level well into the middle of this decade.

Among the other copper porphyries in operation in Australia is the Evolution Mining (ASX:EVN) run Northparkes mine, also in New South Wales, which is expected to produce 23,000-27,000t copper and 40,000-50,000oz gold in FY25.

Its 30-year mine life and massive resource was sufficiently exciting for EVN to pay US$475 million for an 80% stake, highlighting the premium big miners are willing to spend for low grade assets with long mine lives and growth potential.

It comes amid broader positivity for copper, which is expected to see large shortages emerge due to rising demand for poles and wires to service renewables, electric vehicles, urbanisation and AI.

At the same time, major producers Chile and Peru have stagnated and long approval timeframes could see prices surge as supply struggles to catch up, with Bank of America the latest independent analyst last week to lift its price target for the metal beyond US$10,000/t for 2025.

On Friday the three month LME copper contract was priced at US$9476.50/t, up ~11% since the start of 2024.

With all that in mind, we’ve scoured the market for a few companies with the potential to develop Australia’s next large porphyry copper mine.

Alma Metals (ASX:ALM)

Alma will start a scoping study later this year on the Briggs deposit in Queensland, having just collected $750,000 in a raising to extend a drill program where excitement has ratcheted up after the explorer hit a project best intersection of 276m at 0.45% copper from surface.

That included a 49m section towards the top of the hole at over 1% copper.

Continued results like those would deliver the potential to build on an already significant inferred resource, last collated in July last year at 415Mt at 0.25% copper and 31ppm molybdenum, using a 0.2% cutoff grade.

It makes Briggs one of the few deposits in Australia to exceed 1Mt of copper metal, with 28.31Mlb of molybdenum metal also stored in the deposit, sitting in the top 10 undeveloped copper deposits in the country.

Excluding the inferred resource, Briggs also has an exploration target of 480-880Mt at 0.2-0.3% copper and 25-40ppm moly, giving a sense of the scale potential of the Briggs, Mannersley and Fig Tree Hill prospects.

Located just 50km from the deepwater port of Gladstone, Alma has earned an initial 30% JV interest in Briggs from project owner Canterbury Resources (ASX:CBY), and has already committed to the second stage of the three stage earn in.

If it spends $3m on exploration by June 30, 2026, $10 million capped Alma can claim a 51% majority holding, with the possibility to eventually control 70% of the project.

Alkane Resources (ASX:ALK)

Alkane set the market alight in 2019 when it announced the discovery of the Boda porphyry in New South Wales.

Currently a junior gold producer at its small but mighty Tomingley operation, ALK pivoted into the copper developer world with the find.

Along with the nearby Kaiser deposit, it controls open pit and underground resources of 796Mt at 0.33g/t gold and 0.18% copper for 8.28Moz Au and 1.46Mt Cu, or 14.7Moz gold equivalent at prices of US$1950/oz gold and US$8500/t copper.

It’s early days, but a scoping study in July this year focused on a large scale 20Mtpa milling operation showed the combined orebodies could generate $5.7 billion in undiscounted free cash flow over an initial 17-year life at a gold price of $3500/oz and copper price of $15,000/t.

The project would produce 35,600t of copper and 159,300oz gold annually over its first five years, with costs over the life of mine estimated at $630/oz with copper by-product credits.

An estimated pre-tax NPV7 of $1.808bn and IRR of 24% looked positive, though in its current form ALK would be chasing $1.78bn to fund the development.

Likely for that reason, $257 million capped ALK is keen to get a strategic partner on board, while it is also looking at options in future studies to extract the ore via bulk underground mining methods like sub-level caving rather than the long hole open stoping employed at the higher grade Tomingley.

Caravel Minerals (ASX:CVV)

Located not on the eastern sea-board but in WA’s wheatbelt near the farming town of Calingiri, Caravel controls around 3Mt of copper metal at the project of the same name.

150km north-east of Perth, the pitch is the project will produce 65,000t of copper a year over more than 25 years, with additional credits from precious metals and molybdenum.

Caravel placed an initial capex bill of $1.2 billion on the project as a two stage development in a July 2022 pre-feasibility study.

A later update focused on a single 27Mtpa processing train with anticipated all in sustaining costs of US$2.37/lb, with a further update following a metallurgical review increasing plant capacity to 30Mtpa in April 2023 cutting AISC to US$2.07/lb with copper production of 71,000t over its first five years.

Capital investment will be higher at $1.7bn.

Now led by former Fortescue (ASX:FMG) executive Don Hyma, $79 million capped Caravel is continuing to work through a definitive feasibility study.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Alma Metals is a Stockhead advertiser, it did not sponsor this article.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.