Altamin’s Gorno zinc-lead project is proof there’s life in European mining

Pic: Bloomberg Creative / Bloomberg Creative Photos via Getty Images

Europe has a reputation for being a difficult location for junior resources companies to make headway in. That is not the case for near term zinc-lead producer Altamin.

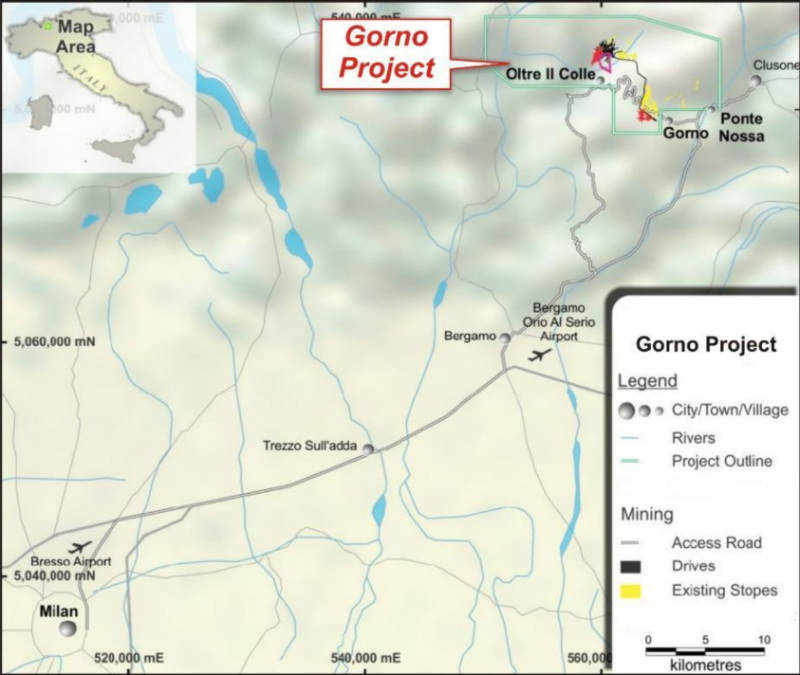

Altamin (ASX:AZI), formerly Alta Zinc, has been operating in Italy since 2015. It is currently progressing its Gorno zinc-lead project towards production, exploring its Punta Corna cobalt project and awaiting the award of exploration licences for two VMS copper projects.

Speaking to Stockhead, managing director Geraint Harris noted that the ASX understood Europe as being too ‘tricky’, as historically, things had not progressed as well for several junior miners.

However, he emphatically pointed out that most of these junior minors had failed to progress due to very specific reasons and that was no blanket ban on mining.

“The perception that Australia has got that there is no mining in Europe, it’s all a holiday destination, is quite wrong,” he said.

“It is difficult in Europe to get new tailings dams permitted but it is becoming difficult everywhere. Social licence is a big thing and if you have a tricky commodity like uranium, it can be quite challenging and local opposition can be quite vocal.”

This does not mean that there’s no mining in Europe with Harris noting that there’s lots of existing mines.

“Lundin and Trafigura have all got established mines in Europe, which are huge industrial complexes and some of their best operating mines, while Sandfire has just acquired Trafigura assets in Spain,” he added.

“Italy also has got lots of geologic endowment, it just has never been explored in modern times and people have really left it alone because they just see Europe as too hard and they think Italy is just Lake Como and the Amalfi Coast.

“It is actually very industrialised and is no stranger to mining.”

While none of Italy’s 25 previously operational base and precious metal mines are currently in operation or have been subject to modern exploration, it still features more than 2,100 industrial mineral concessions for mines and quarries – producing fluorite, talc, barite, graphite, sulphur, salt, sand, limestone, etc. –.

Breathing life back into Gorno

Altamin’s Gorno underground lead-zinc project is one of those 25 historical mines.

A high-grade mine located within a historic zinc and lead mining province with established infrastructure that has been idle since 1982, the company has been fast-tracking work to turn Gorno into Italy’s first operating metal mine in 40 years.

Recent activity has included defining a resource of 7.79 million tonnes grading 6.8% zinc, 1.8% lead and 32 grams per tonne silver – notably higher than its previous 2017 resource – that in turn underpins a scoping study that outlines a robust producer of clean zinc and lead concentrate.

These include post-tax net present value and internal rate of return, both measures of a project’s expected profitability, of US$211m (A$295m) and 50% respectively.

Project capex has been estimated at US$114m with payback expected in just 2.5 years while all-in sustaining costs are estimated at US$0.60 per pound of copper equivalent — well below the LME spot zinc price of US$1.49 per pound. Financing this capital cost is expected to be largely via debt and metal pre-payment.

Mine life is currently estimated at nine years.

“We think we have picked the best zinc asset in Italy that’s going to be a first quartile global operating cost producer,” Harris said.

“Gorno is an advanced development asset, which has been largely de-risked because it has a lot of development in-place, the metallurgy is easy, we have done the technical work and now we have shown that is has good economics.”

Harris pointed out that the company planned to reuse some 15km of previous development in the mine, including a long haulage way, and would only need to develop about 3,000m of new tunnels to access the mineralisation.

“This is a huge advantage not only in cost but also in de-risking. It is always risky to develop new tunnels but if you have got a mine where you have so much development open, you know what the ground conditions are as the technical and physical de-risking has already happened,” he added.

Gorno also benefits from being right in the centre of eight or nine smelters within eight hundred miles – all of which require clean zinc and lead concentrate, that is in short supply across Europe. Gorno’s metallurgy work shows they will be producing some of the cleanest and highest grade zinc and lead concentrates available globally and so it should have strong smelter demand, to reduce treatment charges, and possibly attract potential corporate interest.

Punta Corno

While Gorno is a standout project, it is not the only arrow in Altamin’s quiver.

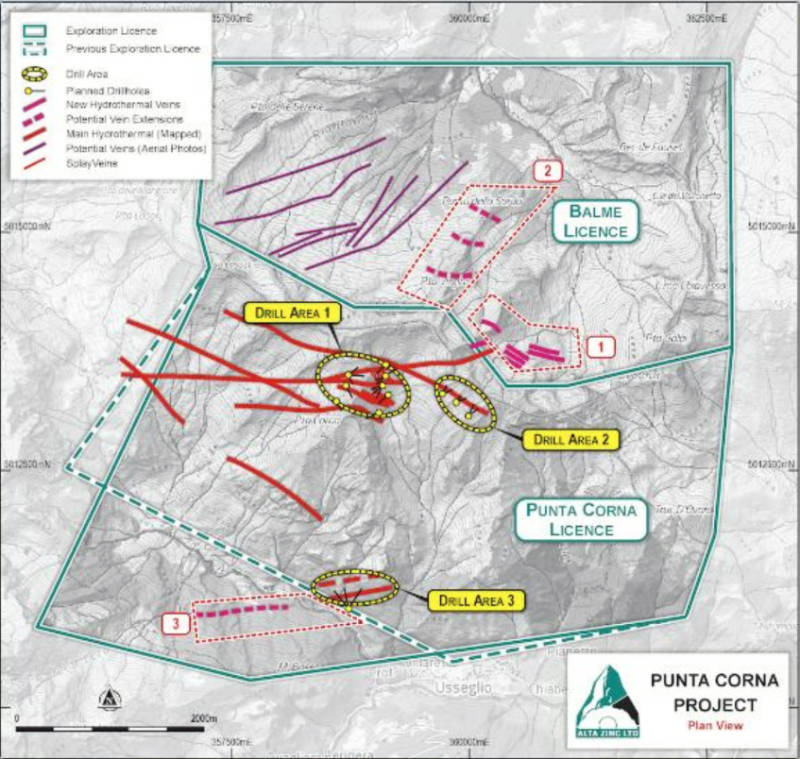

The company’s Punta Corna cobalt project in Piedmont, northern Italy, is in what Harris describes as the ‘sweet spot’. Europe is looking for as a strong cobalt asset in the middle of the growing battery manufacturing industry, he says.

It covers the Punta Corna and Balme exploration licences over the historical Usseglio cobalt mining area where historical bulk sampling reported an average diluted grade of between 0.6% cobalt and 0.7% cobalt over an average vein width of 2m. With the associated nickel, copper and silver credits are considered the in-situ cobalt equivalent grade approximately doubles.

Comparative studies have indicated that the project is like the Bou Azzer cobalt, nickel, and gold deposits in Morocco, the world’s highest-grade cobalt mine.

Punta Corna also benefits from existing infrastructure including a hydro-electric facility and is just 65km from the industrial city of Turin and also Italvolt’s Gigafactory which is under development.

Copper projects

Altamin is also waiting on the Italian Ministry of the Environment to consider public comments for its Monte Bianco and Corchia exploration licence applications and issue concluding documents that will be passed on to respective regional governments for processing and decisions on the decrees as appropriate.

Both licence applications are on VMS (volcanogenic massive sulphide) style mineralisation which hosted multiple high-grade mines that had produced a significant portion of Italy’s copper and manganese up to the early 1970s and were typified by their high copper grades averaging 5-7% Cu.

Monte Bianco also hosts the Gambetesa mine, which was Europe’s s largest manganese producer in the late 1960’s.

Looking ahead

While Altamin has been busy with drilling and Mineral Resource updates culminating in the release of the Gorno scoping study last month, the road ahead will be no less busy.

The company intends to carry out more drilling at Gorno next year, with the view towards further expanding resources later in 2022.

It had previously outlined an exploration target of between 17.4Mt and 22Mt grading between 8.5% and 10.4% zinc, 1.9% and 2.4% lead, and 19g/t and 23g/t silver, which covers about half of its land package.

Additional resources can be used to backfill the latter years of the mine schedule, extending its mine life. A sufficiently large upgrade could also allow the company to increase throughput and bring more grade forward.

Harris expects the company to start and complete a definitive feasibility study before the end of 2022, which along with the completion of metallurgical testwork and grant of the mining licence, will de-risk Gorno to the point that will attract bank finance and make it shovel-ready.

This fast-tracking to DFS is assisted by a lot of its previous work including a pre-feasibility study that was started in 2016-17 but never published because at that time the JORC resource was too small and contained too much Inferred material.

“But all that work has been done, so we have a very clear path to be able to deliver that DFS, which is why we feel confident we can deliver on that aggressive schedule,” he added.

Altamin is looking to make a development decision for Gorno in the middle of 2023 at which point, the bulk of the capital gets spent from the end of 2023.

“We have payback coming in mid-2024, which is quite a short amount of time from when the money is out of the door before seeing payback starting from concentrate production,” Harris explained.

“The other big milestone for 2022 is that we are going to start drilling at Punta Corno, which is obviously pending funding.”

Harris is confident that all this work will position the company well to meet an expected jump in industrial demand.

“Additionally, the decarbonisation and recentralisation of metal supply is very much something that is Europe’s near-term goal and we are very well placed to serve that requirement,” he noted.

“We are also seeing the Italian government starting to put together a database of old mineral projects which they will then make public to try and attract more mine development in the country.

“We have a very strong Italian team and are really an Italian company that is listed on the ASX with a track record of understanding the local requirements and operating within the Italian regulatory framework.

“I think that’s going to give us a big advantage but more than that, it will show the international market that Italy is open for business, but before that happens, we will already have our tenement package, we got to pick the best of it.”

This article was developed in collaboration with Altamin Limited, a Stockhead advertiser at the time of publishing.

This article does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.