война! These commodity prices could rocket if Russia invades Ukraine, experts say

Pic: ru_, iStock / Getty Images Plus

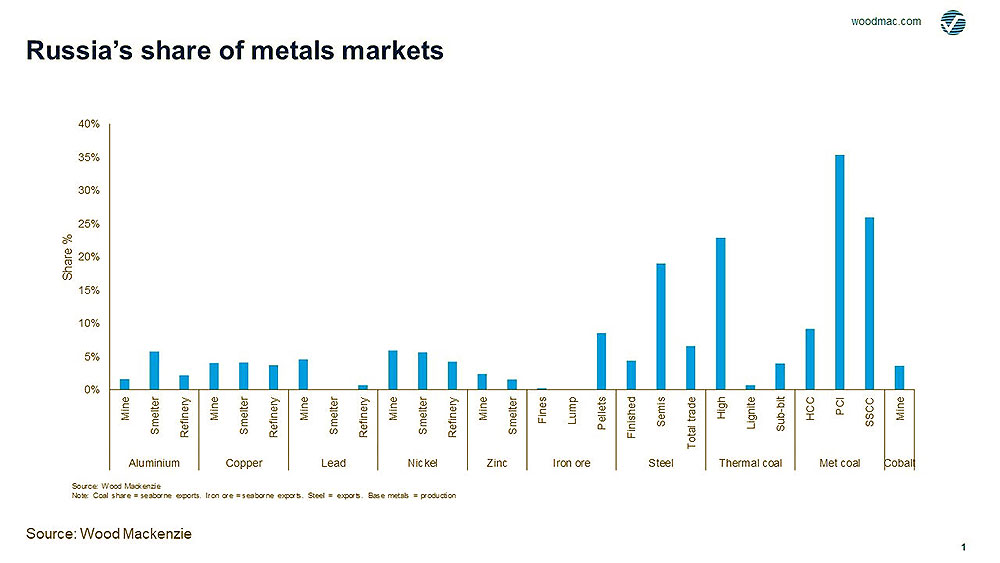

Russia exports a substantial amount of aluminium, copper, lead, nickel, zinc, steel, gas, and coal.

If it attacks neighbouring Ukraine, economic sanctions by the Western world against Russia are a near certainty.

The most likely outcome of a strict sanctions regime would see affected Russian commodities re-directed (probably to China) and European demand backfilled by other sources, WoodMac says.

But the shift will be messy. It could prod already red-hot commodity prices even higher.

Which metals and bulk commodities are most exposed?

A coal day in hell

WoodMac says coal will be a major pinch point.

Globally, prices for met (steelmaking) and thermal (power plant) coal are already sitting at or very close to record highs due to super tight supplies and high demand out of Asia and Europe.

Russian sanctions could tighten supply even further.

“Russia supplies Europe with almost all of its low sulphur-content PCI (Pulverised Coal Injection), and 60% of its high-energy thermal coal,” WoodMac vice president Robin Griffin says.

“A blanket EU ban on Russian coal imports – unlikely though it may be – would guarantee a large hole in EU coal supply.

“US and Colombian thermal coal suppliers would struggle to fill the gap, given the current constraints in those markets, and US coals can also bring with them issues around sodium, chlorine and sulphur contents.”

Meanwhile, replacement for low sulphur PCI (used in steelmaking) would be near impossible in the short term, Griffin says.

“Australia – the only other major supplier of PCI coals – has seen spot PCI supplies dry up almost completely since mid-2021,” says.

All your base (metals) are belong to us

The impact of sanctions on nonferrous metals prices – which are already running hard — could be significant, says Paul Bartholomew, Melb-based metals analyst at S&P Global Platts.

“[Russia] State-owned Norislk Nickel is the [world’s] largest supplier of nickel sulphides,” Bartholomew told Stockhead.

“Along with South Africa, Russia is the world’s largest producer of palladium, a metal used in catalytic converters,” he says.

“This could hurt the European car industry which is already dealing with the semiconductor shortage and further delay the steel demand recovery.

“Russia’s Rusal is also the largest producer of aluminium in the world. The conflict has contributed to rising aluminium premiums in the US.”

Nickel, palladium, and aluminium prices are already up 12.7%, 23.2% and 14.5% year-to-date.

Gas constraints to push up zinc, aluminium prices

Europe is dependent on Russian gas supply to keep the home fires burning and the smelters running, amongst (many) other things.

Gas prices had already been rising this year due to a combination of constrained production and more cold weather in the US; the Russian escalation has just added fuel to the inferno.

“Gas supply, and its impact on other energy markets, dominates fears about the impact of an armed conflict in Ukraine,” WoodMac’s Griffin says.

“All industrial activity in Europe will feel the effect of higher power prices.

“For metals and mined commodities markets, energy-intensive smelting is at most risk, particularly aluminium and zinc, although all base metals production and steel would feel a pinch.”

Power constitutes nearly 35% of the cost of making aluminium on average, and higher in some European smelters, Griffin says.

“An escalation in power prices across Europe has already led to significant aluminium production cuts,” he says.

“Wood Mackenzie estimates that an additional 400 ktpa capacity is at risk of shutting down if energy prices escalate further.

“Europe accounted for 15% of ex-China aluminium supply in 2021 and thus supply cuts could have a material effect on prices for refined metal.”

Zinc smelting is also very vulnerable to energy price rises. At 2.2 million tonnes per annum (mtpa), Europe accounts for 16% of global refined zinc output.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.