The how, what, and why of the NSX — the evolution of an Australian secondary market

Pic: Stevica Mrdja / EyeEm / EyeEm via Getty Images

Starting out as an agricultural market, the NSX is now poised to become a challenger market to the ASX — here’s how that happened, and what you need to know about Australia’s emerging secondary market.

JUMP TO:

The main players behind the NSX

Secondary markets around the world

What the NSX is doing about liquidity

Why the NSX could be the best thing to happen to small companies

How to invest, and the final word

The evolution of the NSX

The history of the NSX

But first, a little bit of history

It started life in Newcastle in 1937 as the Newcastle Stock Exchange, back in the days when Australia had a series of regional stock exchanges rather than a central one.

As you’d expect at that time, it traded mostly in agricultural equities and throughout its history hosted companies such as SunRice and Golden Circle.

But as the centre of Australia’s financial universe drifted south toward Sydney and Melbourne, the NSX found itself a largely provincial and unloved market.

In 1985, things got so dire that the exchange just stopped meeting because there was so little interest in the exchange beyond a few agricultural cooperatives.

It re-opened in 2000, as part of an ambitious plan to tie together the few remaining regional exchanges into one.

Five years later, it merged with the Bendigo Stock Exchange and a short while later it renamed itself the National Stock Exchange.

But it was about two years ago that things really got started.

The team making it happen

“I think there was an appreciation that the NSX offered an opportunity which wasn’t being fulfilled,” NSX business development manager Andrew Musgrave told Stockhead recently.

So, a group of ASX veterans including Musgrave got together with the mandate to turn the NSX into Australia’s true secondary market.

“We see around the world the vital role that secondary markets play, but there just isn’t that here,” he said.

“So our mission has been to really take this opportunity by the horns, to modernise the NSX and really get it going.”

Its first step was moving the headquarters of the NSX from Newcastle down to Sydney, a sign that its outlook was more cosmopolitan than regional.

The NSX’s executive team is littered with experience from the ASX.

Musgrave himself spent nine years drumming up new business in Asia for the ASX, while Yemi Oluwi, John Williams, Chan Arambewela and Greg Fitzpatrick all have experience with the main bourse.

Together, they’ve set about trying to build a true secondary market for Australia.

A quick look at secondary markets

Secondary markets around the world

Secondary markets play an important role in several markets around the world.

London has the AIM secondary market, the US has the NASDAQ, Canada has the TSXV, and Hong Kong has the GEM market.

They offer investors a point of difference and are set up for specific reasons — for example, the NASDAQ was set up for investors who wanted a purely tech-led market, while London’s AIM market was set up to allow smaller companies to attract capital from public investors.

But Musgrave points out that while several secondary boards are owned by the primary exchanges, the NSX is its own company (despite actually being listed on the ASX).

“We see in other countries that the secondary board becomes a very successful, vibrant market in its own right,” he said.

“We feel in Australia, with the amount of investable money here, particularly from superannuation, and the number of companies that are listed on the ASX [more than 2000] that there’s more than enough weight for a second market here.”

Stuart Carmichael, partner at Ventnor Capital told Stockhead that’s something he agrees with wholeheartedly.

“Having a good secondary market would really help lift up a lot of the companies who may not be a great fit for the ASX,” he said.

“Thinking about how much activity that could generate in our economy is huge.”

Ventnor is one of the 20-or-so broking groups who have the ability to trade NSX-listed equities, and is excited by the prospect of the NSX providing not only a way for smaller companies to list but provide competition to the ASX.

“The ASX is a really well-run exchange, but every company needs competition to spur innovation and growth — and at the moment the ASX is the only game in town,” Carmichael said.

But to actually provide a challenge to the ASX for ongoing capital, they’ll need to solve a lot of issues. The first, liquidity.

Liquidity, Liquidity, Liquidity

The problem for the NSX is, and continues to be, the lack of liquidity on the market.

Last year, there were a grand total of 933 trades done with a combined value of $14.4m.

So far this year (at the time of writing), there have been 283 trades with a combined value of $2.4m.

It also has a total of 67 equities listed on the exchange, compared with the more than 2000 on the ASX.

All up the market caps of the companies on the exchange come to $4.8 billion with an average capital raise of $8.3m.

In short, as it stands, it’s very much a broker’s market with a tight range of companies trading.

“Liquidity has really been a legacy issue for the NSX,” Carmichael said.

“But what we can say is that the team at the NSX really has been working hard to fill the liquidity side, and I think all the ingredients are there for them to do so.”

Key to that has been the massive restructure the NSX team has done over the past two years, according to Musgrave.

He said the first step on the journey to liquidity was getting the exchange listed on the IRESS and Bloomberg platforms — so brokers don’t need to order a dedicated machine to trade.

“I think that move has been an absolute game-changer for us, in terms of attracting broker interest,” Musgrave said, something which Carmichael agreed with.

What the team at the NSX has been working on over the past two years is the chicken-and-egg scenario which has plagued the exchange.

It needs a pipeline of new listings to create new entities to trade, but it can only attract those IPOs if it can demonstrate to insiders that there’s a reasonable chance of an exit.

The next step is for the exchange to become available on a retail focused platform like CommSec — something which Musgrave said the NSX team is in discussions about.

“We don’t currently have a Commsec or an ETRADE, but we’re in discussions with both of those firms about coming on as a participant there,” Musgrave said.

Not only would that make trading on the NSX more accessible for the average punter, but it would help attract more brokers to the yard.

“I think the next step in the NSX’s journey is to get that retail flow, to get onto a platform like CommSec — I think once that happens it will unlock the next wave of growth for the NSX,” Carmichael said.

While it’s been quietly solving the tech challenges in the background, only one thing will actually give weight to the NSX: more listings.

The promise of the NSX

Why the NSX could be the best thing for small companies since sliced bread

The NSX has squarely set its sights on the lower end of the market rather than trying to lure an entrenched big fish from the ASX. Musgrave said it’s aiming to lure private companies which could list with a cap between $5m and $50m.

It’s gotten a helping hand from the ASX itself, which over the last five or so years has made it harder to list.

In most cases, these are for very good reasons — such as requiring more focus on director backgrounds after the BigUn and GetSwift debacles.

But, the barriers to listing have become higher in recent times — leading some smaller companies to accuse the main bourse of pulling up the drawbridge.

“We feel with the ASX and their size they tend to have a one size fits all approach which doesn’t sit well with those smaller companies when it comes to listing, and with the overheads which come with that,” Musgrave said.

“The feeling in the market is that the ASX is making it harder for those small companies to float, whether or not they feel those small companies are not appropriate to list or they feel it’s too soon for those companies — that’s probably happening a bit out there.

“From our perspective, we don’t put those small companies into one group. We like to treat each company on a case-by-case basis.”

Carmichael said it had become harder and harder to list a company throughout his time in equity.

“I would say it’s definitely ramped up over the past three or four years — and it’s definitely harder to list for a small cap company,” he said.

“Undoubtedly it makes the companies able to make it to the ASX stronger, but the way it is now…smaller companies are thinking twice about an ASX listing and are remaining private for longer.”

That’s great news for the NSX, which has set its sights on two sectors to grow its IPO pipeline: mining and fintech.

The type of companies on the NSX

So who’s there now, and who might be there tomorrow?

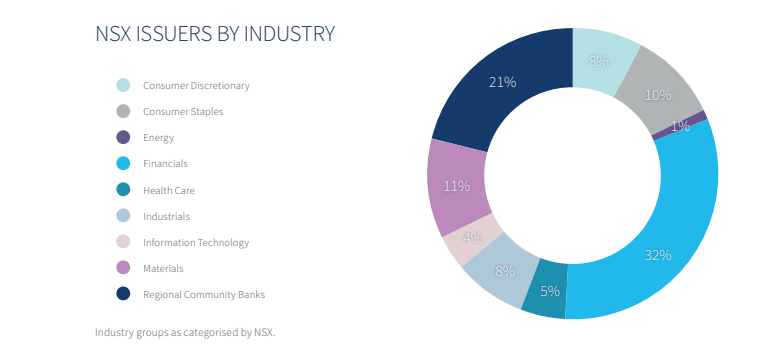

While the NSX started life as an agricultural exchange, there are a good mix of different sectors represented on the boards.

From the NSX’s 2018 annual financial report

But the NSX has set its sights on the mining space and fintech spaces for growth.

Musgrave said the NSX offered fintechs a compelling proposition.

“The fintech market has become very vibrant in the last few years — and those sort of companies can pop up anywhere,” he said.

“So we’ve been really driving to engage with a lot of the incubators and accelerators in the space around the country because we feel those companies may think an ASX listing may be a bridge too far, or is too expensive.”

Musgrave confirmed to Stockhead that it had been working with intermediaries such as accountants, brokers and law firms to get its name in front of more fintechs.

But Carmichael feels the NSX’s push to lure more mining companies, particularly in Perth, may bear more fruit.

“There are definitely some exploration companies here in WA that you wouldn’t list, because they basically have no assets, but they’re led by some really great teams,” he said.

“What the NSX could do is provide a way for those companies to access capital without having the assets there — which are hard to generate because it’s an exploration company.”

Musgrave said the pitch to miners had been well-received — mostly because of its commitment to take a more intangible approach to valuing a company.

“It’s not so much the sector, but what it comes down to is how successful that business has been over the past couple of years,” he said.

“So we look at a two-year track record rule that the company needs to adhere to…but when it comes to something like an exploration company that hasn’t been in business for two years we’re flexible on that.

“In that case we look at what the management and directors have been doing over that period of time — if they’ve got a lot of expertise in that sector there’s a bit of flexibility over that.”

It’s a commitment to slashing the red tape associated with listing that is the NSX’s main weapon in trying to attract more IPOs — and that suits emerging miners down to the ground.

How and why to invest

Musgrave is quick to point out that the NSX shouldn’t be read as a challenger to the ASX — it just wants to build an alternative.

At the moment, if you wanted to trade NSX equities you need to get in touch with a broker, and to be frank, it doesn’t offer a lot of liquidity.

But with plans to get onto more retail-focused platforms such as CommSec and others and a plan to build its pipeline of IPOs, the NSX could emerge as an investment opportunity in the next couple of years.

“In five years we want a lot more IPOs on the market — but at the end of the day we’ve got an exchange with a tier-1 license which is the equivalent to the ASX,” Musgrave said.

“We’re working really hard to get more of the online brokers onto the platform, and we’re here to provide competition in financial markets and the IPO world.

“It’s about creating an alternative to the ASX for companies to list, and competition is a good thing because it drives innovation and drives down cost.

“It’s not about stealing business away from anybody else, because it’s about growing the pie. As the IPO and listing world gets bigger, then it’s good for everyone.”

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.