What the JORC? Why mining jargon is so strange and what it really means

Miners and mineral explorers make up the bulk of ASX small cap investing opportunities — but they don’t make it easy with all the big words.

Miners often release announcements that are heavily laden with jargon the average investor may not understand.

Making matters more challenging, some of those technical phrases have officially recognised meanings — while others have very little meaning at all.

Here we’ve set out to translate some of the more common mining jargon that appears in ASX announcements.

Exploration

Resources companies are either undertaking “greenfields” or “brownfields” exploration.

Greenfields is exploration done in new areas where mineral deposits have not yet been discovered.

Brownfields is exploration done close to previously discovered deposits and mines.

This is the type of exploration usually done by producers to “grow” a “resource” or “reserve” — to boost production and extend the mine life.

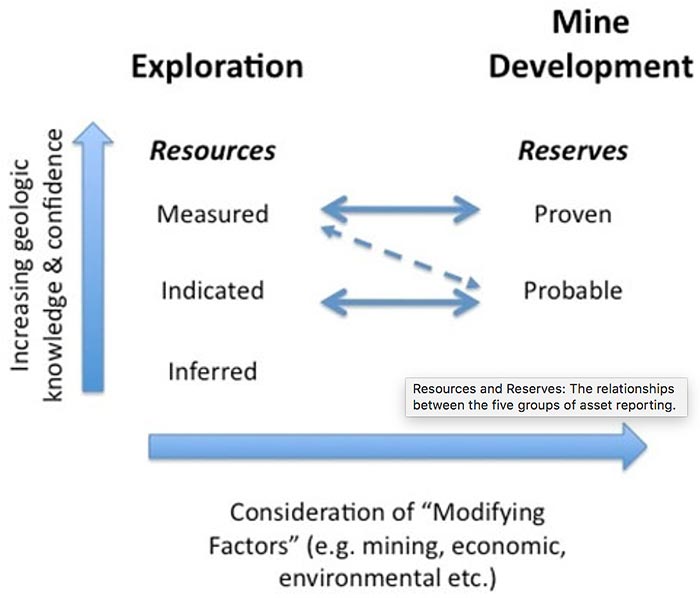

Typically “reserves” refer to discoveries that are commercially recoverable using existing technology, while “resources” are either not yet commercially viable or are mere speculation.

To “grow” a “resource” typically means to find new information that shows an existing deposit is bigger than previously thought.

Mineral resources are categorised in order of increasing geological confidence from inferred to indicated to measured.

Inferred resources are estimated using limited geological evidence and sampling information, which means there’s not enough confidence to evaluate the project’s economic viability.

Subsequent surveys might uncover new information allowing a resources to be upgraded to “indicated“, meaning a company has sufficient information on geology and grade continuity to support mine planning.

A “measured” resource represents the highest level of geologic knowledge and confidence.

Reserves are often broken into “proven” and “probable“.

A proven reserve is an estimated quantity of a mineral or oil or gas that is able to be economically recovered with high certainty.

Probable reserves are a bet each way at about 50 per cent certainty. “Possible” reserves are a long shot with about 10 per cent certainty — and typically haven’t been tested by drilling.

Resources are often referred to as “contingent” (where a resource’s commercial viability might be continegent on unresolved issues such as regional political stability) or “prospective” which is not much more than a best guess.

Feasibility studies

Miners usually undertake four different types of studies when examining the potential of a resource. These are scoping, preliminary feasibility (PFS), definitive feasibility (DFS) and bankable feasibility (BFS).

These determine whether or not a resource can be mined economically.

“Within each of those various categories, there’s a certain amount of work that needs to be carried out and there’s a certain confidence level based on that work that is appropriate for a company to be able to use that particular definition and tick that particular box,” says resources expert Gavin Wendt.

“When an investor just hears of a scoping study or an inferred resource or proven and probable reserves, there isn’t necessarily an understanding of the amount of work and the confidence level that has to be met for all companies to be able to publish.

“I think companies could do a much better of explaining that simply. I think the ASX has tried to, in their own ham-fisted sort of a way, educate the average investor.”

The problem right now is that there is no real standard for explaining the ins and outs of each of these studies and what they actually mean.

Wendt argues that the ASX has actually made it harder for companies to get their message across.

“I think companies sometimes do their best and in other instances sometimes the companies try to muddy the picture as much as they can,” he said.

“But there’s not really a standard. That’s what the ASX has tried to introduce.

“They’re not helping the investing public. Most of the rules they’ve brought in have just made life harder for companies.

“In the old days, if a reputable group of directors picked up a project and did some work on it and came out with a scoping study, they could publish forecasts and guidelines which would give the average shareholder in a company a really good understanding of where this project might potentially go.

“Now a company will do a scoping study and they’re not allowed to talk about the results.”

Drilling

There are several stages and types of drilling that explorers will do in their bid to make the next big discovery.

Aircore drilling is an earlier stage type of drilling that bores a hole into the ground down to depths of 50-60m. It injects compressed air into the hole to remove drill cuttings that are sent off for analysis.

Diamond drilling is a rotary type of rock drill that cuts a long cylindrical core 2cm or more in diameter.

This type of drilling is usually done to recover mineral samples from depth or from within areas that are harder to drill.

Reverse circulation (RC) drilling is used to gather preliminary data on minerals and is cheaper and faster than diamond drilling.

This type of drilling uses rods with inner and outer tubes and the drill cuttings are returned to surface inside the rods.

Wendt said miners need to put themselves in investors shoes and explain things like drilling more simply.

“Very often investors don’t have any idea what the drilling is about,” Mr Wendt explained.

“Is it shallow, is it deep, is it trying to just provide some information about the geology or is trying to define the aerial extent – the dimensions – before they start narrowing in with some later drilling?

“There should be a paragraph or two to explain that.

“You’ve got to get the story across, whether it’s good or bad you have to explain your mums and dads type of investor.”

Geology

When it comes to geology there are many different terms resources companies will throw up in the ASX announcements.

Sulphides are a type of ore containing oxygen-free compounds of sulphur and are usually found deep below the earth’s surface.

Copper and nickel are examples of minerals that can be found in sulphides.

Chalcopyrite is a sulphide mineral of copper and iron and is the most important ore mineral of copper.

Conglomerate is a term that has come up quite a lot recently, especially after Artemis Resources (ASX:ARV) and its Canadian partner Novo Resources uncovered gold nuggets that were later confirmed to be conglomerate-hosted.

Conglomerate is a sedimentary rock consisting of rounded, water-worn pebbles or boulders cemented into a solid mass.

Volcanogenic describes the volcanic origin of mineralisation.

Pegmatites are rocks formed from lava or magma that often contain rare earth minerals and crystals. They are the primary source of lithium.

Porphyry is also rocks formed from lava or magma that has large crystals in a fine-grained mass.

These types of deposits are usually quite large but low-grade. Globally, over 60 per cent of copper, all of the world’s molybdenum, 10-15 per cent of uranium and a significant amount of gold comes from porphyry deposits.

ASX gets tough on miners

The ASX has been cracking down on explorers over various issues such as companies that are nowhere near production reporting what the bourse considers to be a “production target”.

It’s not uncommon for companies – particularly excitable juniors trying to light a fire under shareholders – being forced to retract statements.

The corporate regulator ASIC says it is common for investors in resources companies to put a lot of emphasis on “forward-looking statements” when considering an investment.

But the regulator says companies need to be careful because those that publish non-compliant forward-looking statements “take legal and reputational risks”.

A forward-looking statement is a statement about a future matter, such as production targets and forecast financial information.

In 2016 the regulator released a revised draft of its regulations around forward-looking statements provided by miners following two years of discussions with the industry.

ASIC said at the time that it had made some minor drafting changes to clarify its guidance in response to concerns and misunderstandings that arose at the time of the original release of its regulations in April.

The regulator clarified that production targets and forecast financial information can be published even if secured funding is not in place, but a company still needs to be able to demonstrate “reasonable grounds” that it could obtain the necessary finance as and when required.

Production targets and forecast financial information can also be published based not only on reserves but also on resource estimates provided there are “reasonable grounds” for that estimated mineralization and each of the JORC Code “modifying factors”.

JORC refers to the mining industry’s official code for reporting exploration results, mineral resources and ore reserves, managed by the Australasian Joint Ore Reserves Committee.

“Modifying factors” are considerations used to convert resources to reserves.

These are things like mining, processing, metallurgical, infrastructure, economic, marketing, legal, environmental, social and governmental factors.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.