Are bonds cheap now that inflation has peaked? Here’s what an expert says, and a quick explainer

As inflation peak, bond prices look cheap. Picture Getty

- As inflation peaks, bond prices look cheap

- A quick explainer on bonds

- Stockhead reached out to Betashares’ chief economist, David Bassanese

The yield on the benchmark 10-year US Treasury note reached its highest levels since 2007 earlier this month.

In Australia, the 10-year Government Bond yield is also trading at an 11-year high, sending bond prices much lower (note that a bond price declines as its yield rises).

But as inflation peaks, most traders are convinced the outlook for the bond market has now become more positive.

The ABS report on Wednesday showed that Australia’s inflation has eased to 4.9% in July – the lowest in 17 months – from 5.4% in June.

Data released in the US also reinforced the suggestion that the economy is cooling. This week, US GDP growth came in at 2.1% for Q2, versus the official estimate of 2.4%.

Experts now believe the Fed’s rate hiking campaign is having the cooldown effect it’s been seeking, and the case for more rate hikes in September, and perhaps even in November, is fast receding.

David Bassanese, the chief economist at Betashares, says he’s been a little surprised by the bond selloff in recent weeks, particularly since central banks have basically reaffirmed that they’re on hold.

“I think there’s a good chance that we’ve seen the last of the rate hikes, and there’s also a very good chance that rates will be cut next year,” Bassanese told Stockhead.

He explained that the recent selloff in bonds was mainly due to the US credit downgrade, as well as traders ruling out rates easing in the first half of 2024.

But these elevated yield levels, he said, could soon start to unwind.

“I think broadly, bond yields are plateauing at these levels, and my view is that they do represent good value for bond investors.”

Bond price vs yield

For beginners, it’s important to note that bond price and bond yield are inversely related, i.e.: as the price of a bond goes up, the yield decreases and vice versa.

The reason for that is simple: while the coupon rate of the bond remains fixed, the prevailing market rates fluctuate on a daily basis.

So as market interest rates rise, the fixed coupon on the bond becomes less attractive – pushing bond prices lower.

Conversely, as market interest rates fall, the fixed coupon on the bond becomes more attractive – pushing bond prices higher.

What this then means is if you bought or sold a government bond before maturity date, you could gain or lose despite receiving fixed coupons.

Real life example

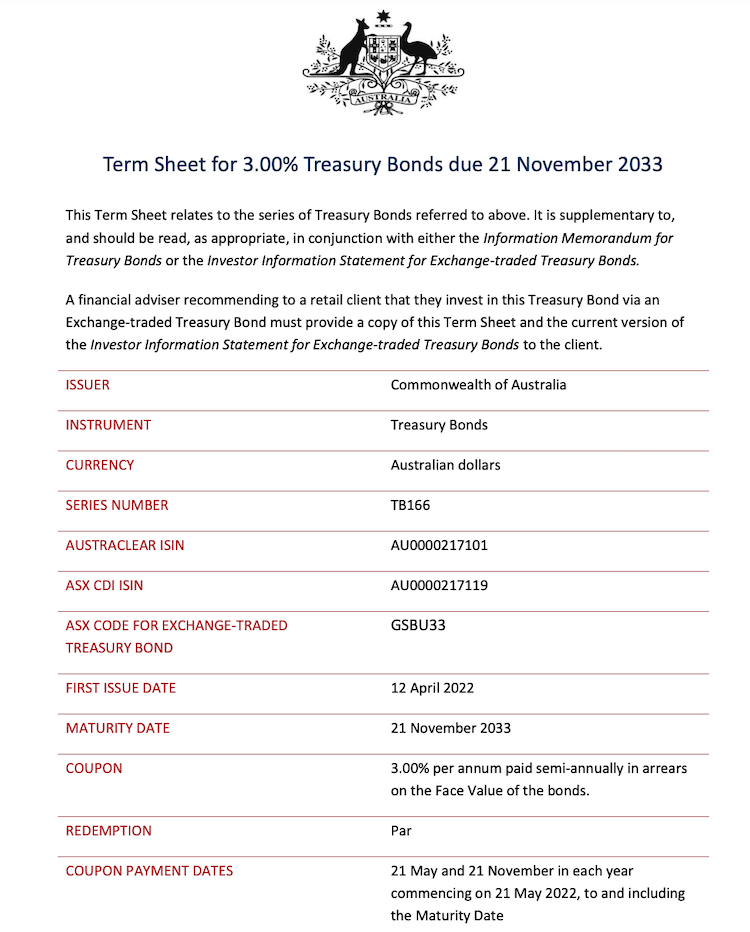

Here’s a relatively newly issued Australian Government bond:

It’s an 11-year bond issued on 12 April 2022 at a coupon of 3%.

As one year has passed since issuance, the note has now become a 10-year bond – or in market parlance, ‘it’s rolled down the curve’.

Investors who bought the bond on issue date would have paid a par price ($100 face value) for it, at a precise yield to maturity of 3% (yield equals coupon at issuance).

They were also guaranteed (by Treasury) that if they kept the bond until maturity (21 November 2033), they would be getting 3% in coupons every 6 months, and their full principal back on maturity date.

But what if they wanted to sell the bond before maturity?

Well they could, but the bond price fluctuates and has now declined from $100 to $91.40, with a yield to maturity of 4.075% (at the time of writing).

The price has declined because essentially, who would want to receive a 3% coupon when the prevailing interest rates in the market is above 4%?

This then takes us to the concept of yield to maturity.

When an investor goes into the market now and buys the bond at $91.40 with a yield to maturity of 4.075%, they have practically locked in a guaranteed return of 4.075% if they kept the bond until maturity date. Hence the term ‘yield to maturity’.

This is because while they would still be getting a coupon of 3%, they’ve paid a much lower price for the bond ($91.40 instead of $100).

A couple of bond ETFs on the ASX

Bassanese told Stockhead that he likes the looks of the longer end of the bond curve right now.

“We’ve had what’s called a bear steepening at the moment, where longer term bond yields have moved up relative to short term rates,” he explained.

But at the end of the day, Bassanese says the shape of the curve in the Australian market is relatively flat compared to the US.

Because of that, investors are unlikely to get that much of a yield pickup holding long dated Aussie bonds compared to shorter ones.

And while one could buy individual bonds directly in the market, he recommends that investors look at the bond-focused exchange traded funds (ETF) offered by Betashares.

According to Bassanese, the BetaShares Australian Government Bond ETF (ASX: AGVT) are for those worried about credit risk and the economy falling into a recession.

“The safest duration play would be long duration government bonds, where you take no credit risk. If the economy does slow, credit spreads could widen and that would hurt corporate bonds.

“So if you’re worried about that, you know, AGVT is the standout global Australian bond exposure,” he said.

But if you’re prepared to take on some credit risk, Bassanese recommends the Betashares Australian Investment Grade Corp (ASX:CRED).

“At the moment, credit spreads are still relatively high. But if we have a soft landing, Australian credit spreads could narrow, and you’d benefit from holding the CRED ETF.”

ETF prices today:

The views, information, or opinions expressed in the interview in this article are solely those of the interviewee and do not represent the views of Stockhead.

Stockhead has not provided, endorsed or otherwise assumed responsibility for any financial product advice contained in this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.