Westpac raises rates; monthly NSW mortgages rise by $1k; furious CPA: We want an accounting!

Extremely pissed off accountant. Via Getty

Australia’s oldest and most experienced bank is taking a leaf out of the RBA playbook and getting out in front of trouble.

Westpac says it will pass on Tuesday’s surprisingly robust cash rate hike in all its fulsome glory to its customers from June 21, lifting the bank’s mortgage rates by 50 basis points.

This makes Westpac the first of the big four to pass on to those with variable home loans what was the most substantive rate hike in more than two decades, after the Reserve Bank’s (RBA) board chose to raise by another 0.5% taking the official cash rate to 0.85%.

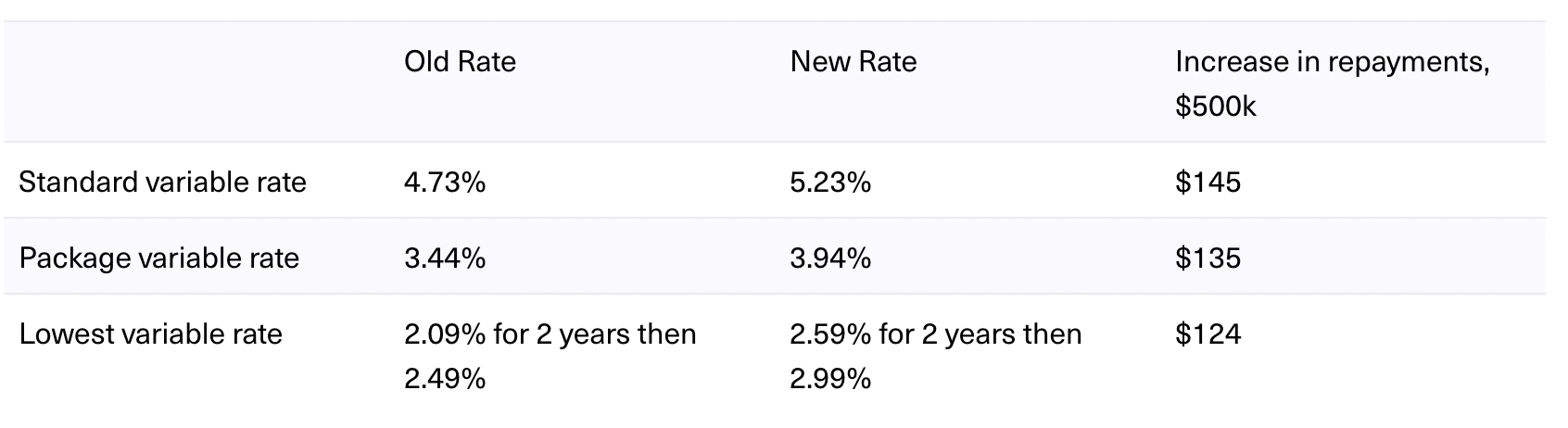

Here’s the impact of a 50bps (0.50%) hike on Westpac variable rates:

$1000 more dollarbucks a month

In its post-match statement, the bank reiterated it will “do what is necessary” to return inflation to target and “normalise monetary conditions” – RBA shorthand for more hikes are on the way.

In justifying the biggest increase in 22 years, the RBA put forth this argument, joyously condensed:

-

The Australian economy is comparatively resilient

-

The unemployment rate has fallen to just 3.9%, suggesting the labour market is strong

-

The RBA continues to point to higher wages growth

-

Inflation is expected to accelerate and has already increased beyond last month’s expectations

-

Energy costs most concerning – with higher prices for electricity, gas and petrol

-

RBA says it is also following a path taken by the US, Kiwis and the Canadians

-

Getting ahead of inflation is how best to contain its surges

-

RBA is working from an historically low starting point

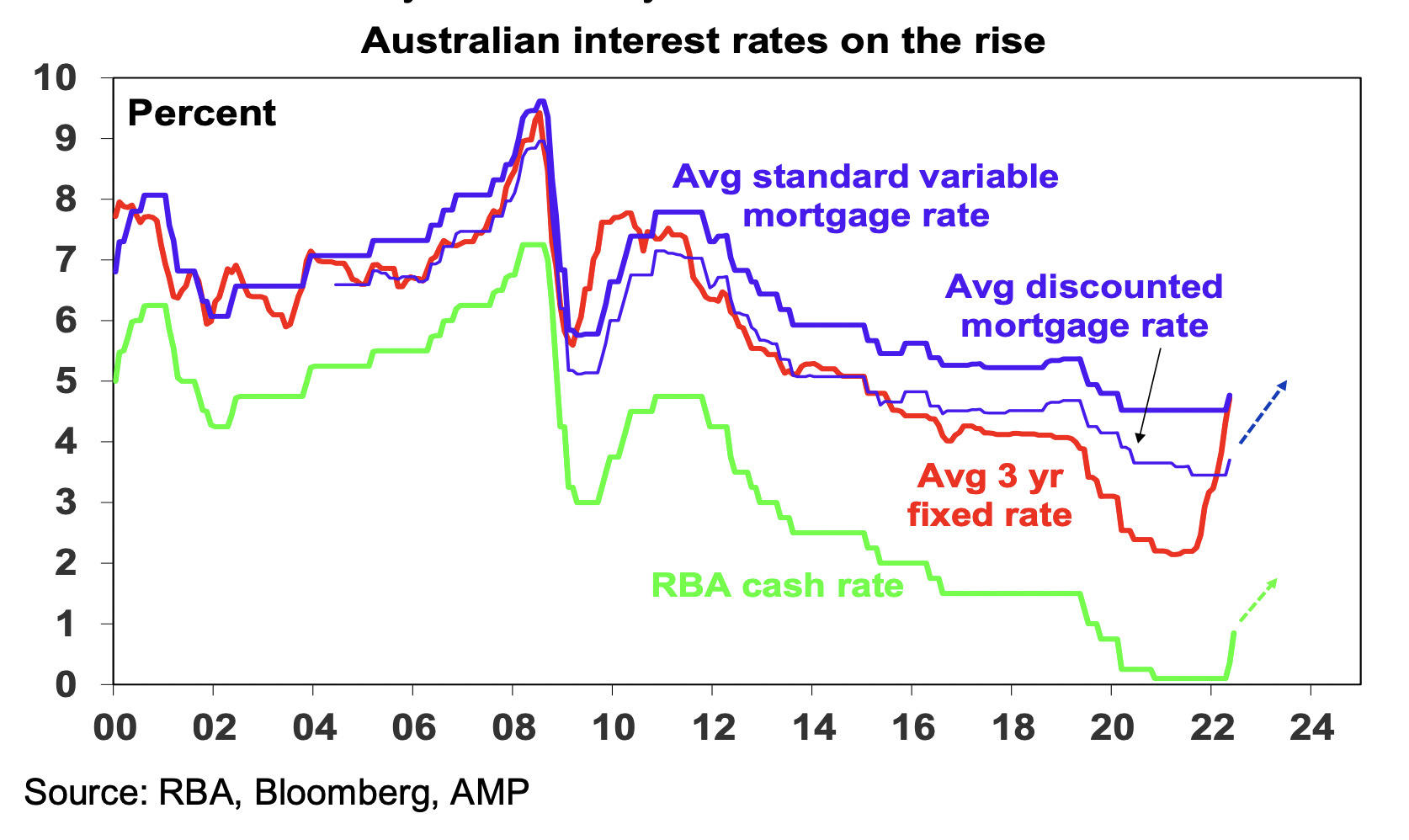

Dr Shane Oliver, head of investment strategy and chief economist at AMP Capital, says the hawkish nature of the RBA’s post meeting statement appears to underpin futures market expectations for the cash rate to rise above 3% by year end and then 4.5% by mid-2023 and to then stay above 4% for the next two years.

“However, it’s likely that the cash rate won’t have to go that high before the RBA achieves its aim of cooling demand enough to take pressure off inflation and keep inflation expectations down,” Dr Oliver says.

The mitigating factor according to AMP is that household wealth is up more than household debt but that doesn’t mean there won’t be ‘a significant amount of pain’ as rates continue to rise.

The RBA’s own analysis suggests that by the time the official cash rate hits 2%, about one out of every four variable rate holders would see a 30% or more rise in mortgage payments from a 2% rise in rates.

So a new borrower in NSW – where average new home loans are circa an eye-watering $800,000 – can expect monthly payments to rise by more than $1000 if the cash rate rose to 2.5% compared to what they were paying back in March.

“This is a huge hit to the household budget,” Dr Oliver says.

Statewide Super’s economic guru and head of skepticism, Con Michalakis:

RBA nerds doing pic.twitter.com/fD2BAGLWsM

— Con Michalakis (@MichalakisCon) June 7, 2022

Matt Simpson, market analyst at City Index, says the central bank’s 75bps rocket over the past two meets makes it their most aggressive back-to-back meeting ever.

“I really think the RBA have restored some credibility today by coming out swinging – they may have taken a leaf from RBNZ’s book, but it needed to be done with inflation running so hot.”

Simpson says while the board stopped short of assuring they’ll continue to hike in 50bps increments they acknowledged an expectation to “take further steps” to normalising policy.

“And as they themselves stated the neutral rate is estimated to be between 2-3%, it still leaves room for several more hikes on the table.”

Calling for an accounting

But not everyone is as admiring of the way our central bank has gone about its business, with the CPA calling out ‘a major flaw’ in the way Australia reports inflation.

“In reaching (the) decision, the RBA has relied on CPI figures for the March quarter,” says CPA Australia’s Gavan Ord.

And that’s no good. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is probably the Tom Cruise of indicators upon which the RBA bases its decisions. But Australia reports CPI quarterly, unlike most other advanced economies which do the CPI read every month.

“These are the same figures it relied on to raise interest rates by a quarter of a per cent in May; and will be the same figures it relies on at its July meeting.

The solution, according to the peak accounting body is bloody simple: move to monthly CPI reads, like everyone else.

“We have a limited understanding of the impact May’s interest rate rise had on inflation. By contrast, the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England, for example, all have access to data within weeks of making a decision,” Ord says.

CPA Australia supports the RBA’s latest call, but is screaming – as only chartered professional accountants can’t – for the new government to go monthly with the price index.

“We’re in a high inflation environment; we need to be agile,” Ord warns. “This necessitates a degree of urgency to this proposal.”

“Relying on quarterly CPI data when the rest of the world gets it monthly, is like waiting at your letterbox for updates when your neighbour gets them on their phone.”

And that, in the parlance of my youngest, is what we call a sick burn.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.