Two years, one pandemic, six changes that rocked Aussie property to its illogical core

Pic: Rommel Gonzalez / EyeEm / EyeEm via Getty Images

INT. Night.

A study filled with books in what looks like a grand old Victorian terrace in Paddo, or maybe Woolahra.

A not-too middle-aged, but definitely handsome man with a touch of grey in his full-bodied hair, smoking jacket and a brandy swivels to face the reader.

A warm fire burns, illuminating a full library to one side, and to the other: a giant cut out of Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard looms.

A leopard on a golden leash purrs quietly.

ME:

The global pandemic has changed our lives in so many different ways.

We’re coughing on each other less; it’s so much easier to get out of work; and in 2022, even if you’re the Russian President – it’s just really damn hard to invade a stranger’s personal body space. It sure has been a grande olde discombobulation of the way we go about being us.

Delta, Omicron and their seemingly endless offspring also upended the nature and shape of our already freaky Australian housing market.

From the constant lockdowns, the Reserve Bank’s boot on the neck of record low interest rates… to the absurdist flight from the cities to the country-side, the catalysing impact of WFH, generous government home buying incentives and the psychological turmoil of this uniquely odd pandemic, has had some really , truly distinct impacts on – in the words of CoreLogic’s prolific head of research Eliza Owen – “the very composition of buyers and the dynamics of the housing market.”

So from the doyen of data, here are six ways Owen says the property game has changed:

1. Australian home values up 25%, to record highs

Since the onset of COVID-19 – despite an initial moment of doubt – Aussie housing values on the CoreLogic Index rose 24.6% between the end of March 2020 and February 2022. Soaring demand followed record low interest rates, high household savings, a bunch of government grants and a sharp fall in supply.

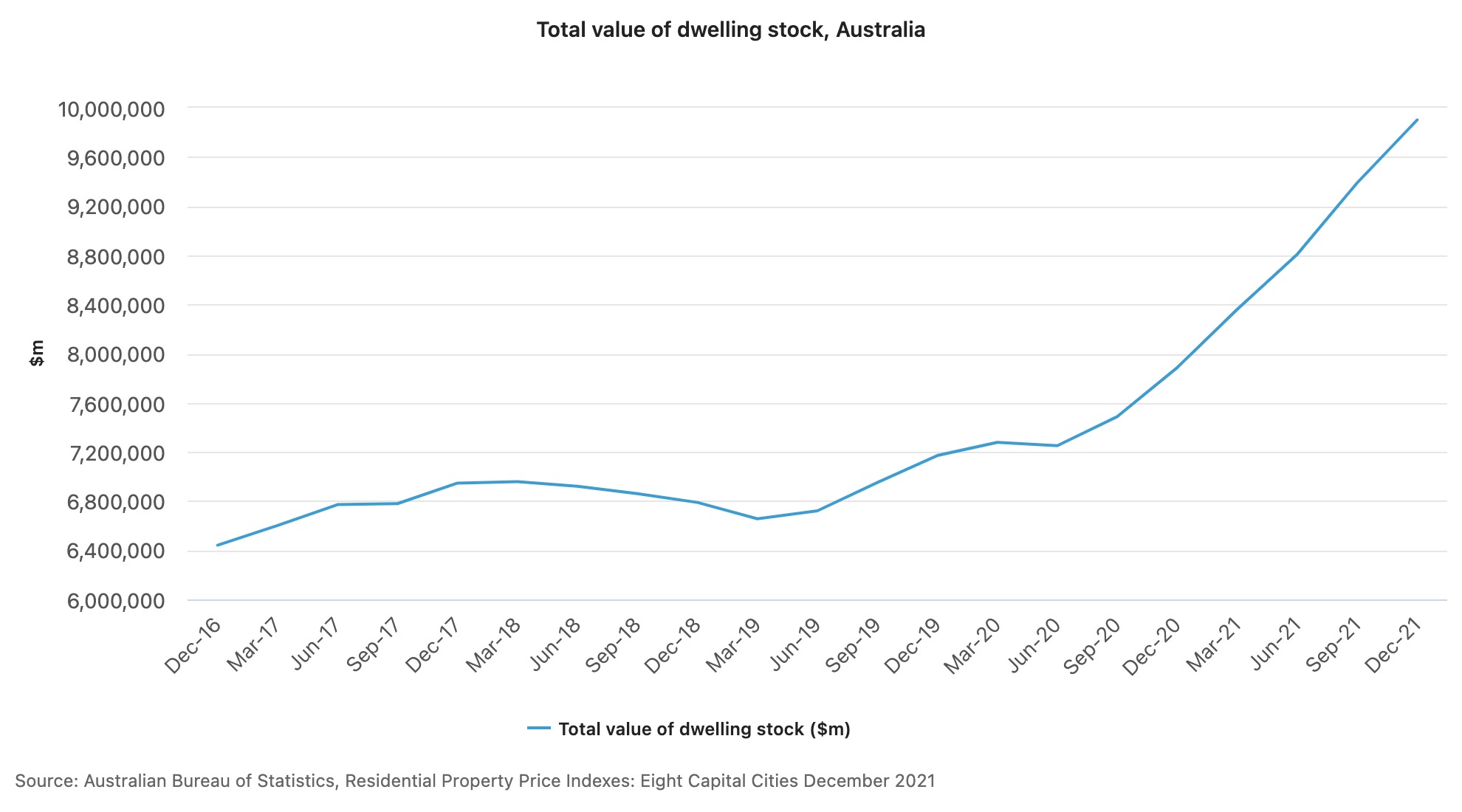

Last month the total value of residential real estate sat at $9.8 trillion. It was $7.2 trillion when the pandemic took off.

During the pandemic, the Bureau of Stats says the average cost of an average Aussie home went up by $173,805, to $728,034.

2. At first, First Homebuyer’s got in some early licks

Yes, that initial fall in house prices opened up a rare ray of sunshine on first homebuyers – affordable options emerged in this false-Spring downturn. There was record low mortgage rates and an upsurge in government incentives.

From June 2020, first home buyer activity surged on the intro of HomeBuilder scheme, alongside the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme, and there were state-based grants and stamp duty concessions all speaking to first homebuyers.

That looked the goods until about January 2021, then as housing values substantially outpaced incomes, the ‘firsties’ were played out of a game which was about to get exclusive.

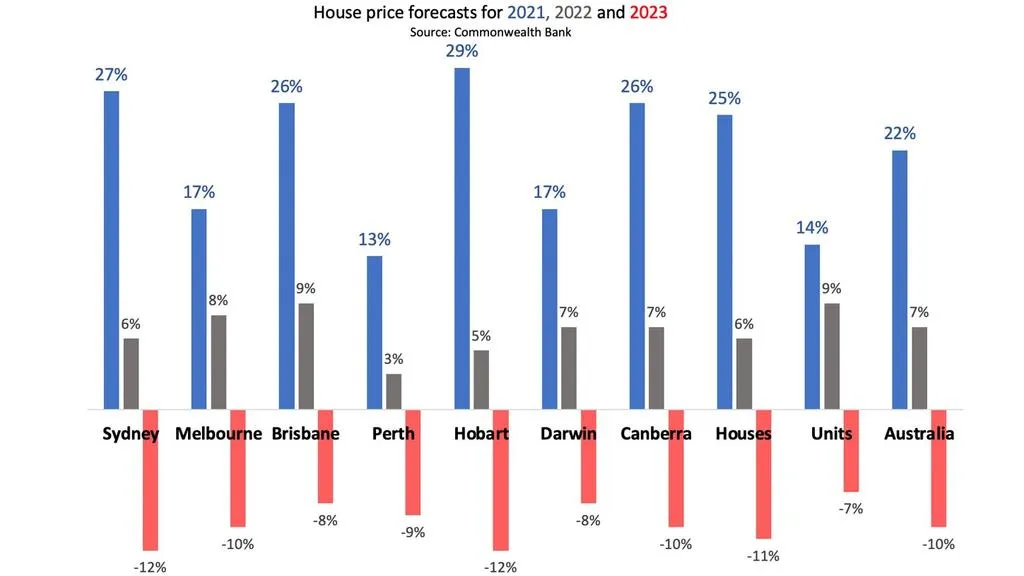

The Commonwealth Bank is predicting that house price growth will slow down substantially in 2022 and then actually go backward in 2023.

3. Rents went nuts to record highs, gross yields fell to record lows.

While rents saw a wee decline of -0.8% between March and August 2020, the lull was brief and the surge through 2021 was ugly. Over the course of 2021, annual rent value growth was at its highest levels since 2008. Across Australia, median advertised rents since March 2020 have risen $30 a week to $470.

There are a bunch of reasons here, Owen says.

“Investor activity had been relatively subdued between 2017 and mid-2020, contributing to rental supply constraints. Rental supply may also have been eroded through the rise of rental services like Airbnb, which have enabled property owners to pivot to the short-term rental accommodation market.”

This latter trend may have been particularly prevalent in tourist spots, some which really flourished amid a rise in domestic tourism over the past two years. Meanwhile, new investors amped up rents due to the rising purchasing prices, yet gross rental yields fell.

“This is because gross rental yields are a portion of the purchase price of a property, and purchase prices of properties have grown 24.6% since March 2020, outpacing the 11.8% rise in rents,” Owen says.

4. Housing debt is also at filthy, record highs

We can lay the vast acceleration of housing and rent values largely at the feet of the RBA. So let’s do it.

With the RBA setting the official cash rate target at 0.1% circa November 2020, lower debt costs enabled borrowers to get their mitts on lots of cheap credit.

As of January just past, our combined outstanding housing credit sat at a record high of over $2 trillion, while the ratio of housing debt to household income was at a record high 140.5% through Q3 2021.

Now, high levels of housing debt, particularly where it’s outpaced incomes which just ain’t rising, is not good for a healthy Australian economy. We’ll see how unhealthy as rates climb this year.

5. House prices compared to units – yup – new record highs

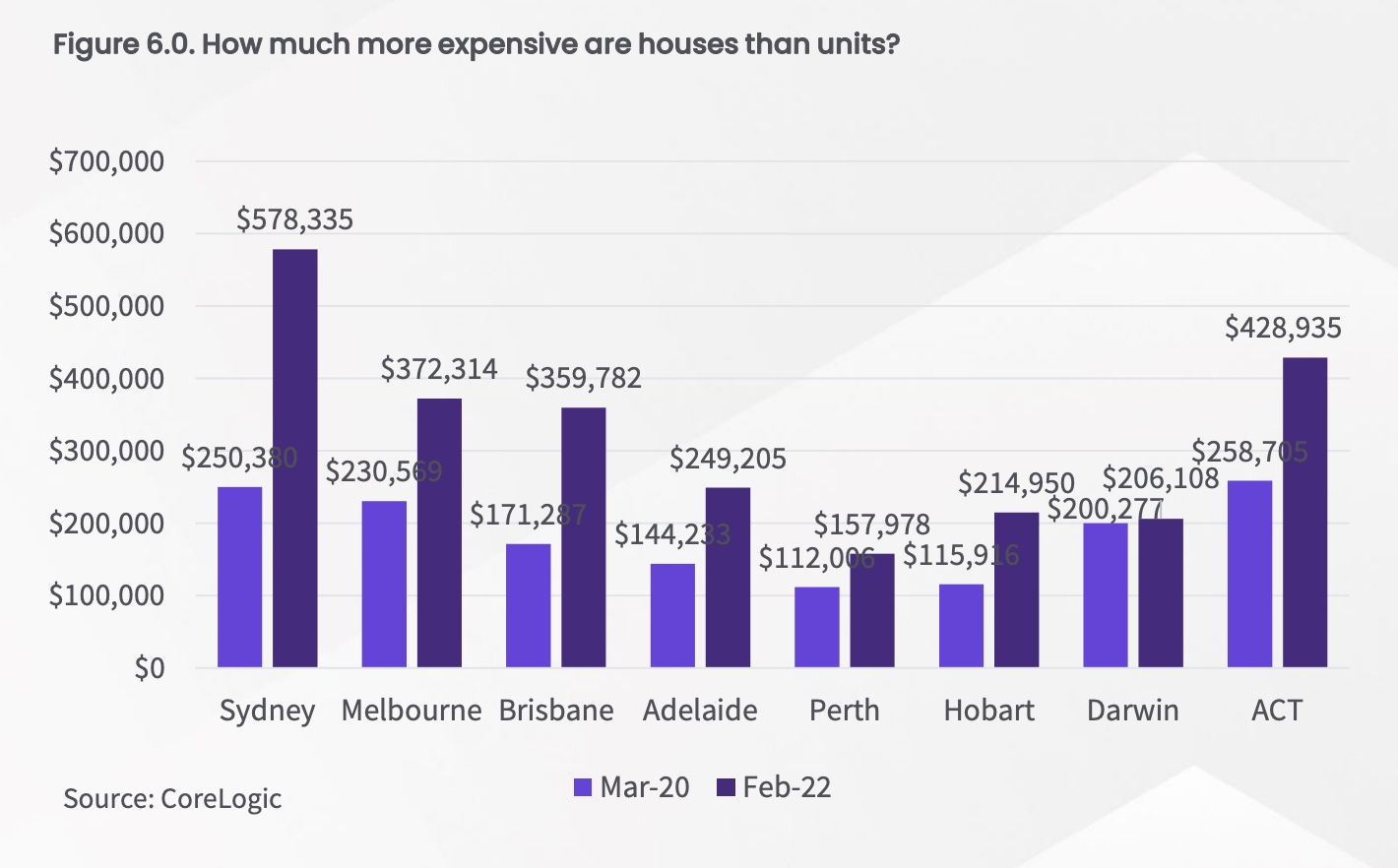

Both the composition of the buyer pool and the impacts of COVID may have contributed to a record gap between house and unit values, Owen says.

“Investors, who may have a preference for units, have been a relatively small part of demand through the upswing. Additionally, detached houses may have been in higher demand as Australians spent more time at home through the pandemic.”

Then the old HomeBuilder grant funnelled a bit more demand for detached housing. The result is a record high gap between house and unit values.

6. Moving to the country, gonna eat a lot of peaches / let’s get the hell out of Dodge

Yeah. Regional Australian house price gains totally outpaced the cities. The gains across regional Australian dwelling values has been almost 40% since March 2020, while capital city home values have increased around 21%.

Eliza says, “in lifestyle regions, which have become intensely popular in the past two years, new million-dollar markets have been created across areas such as the Sunshine Coast, the Illawarra and the Gold Coast, in those spots alone, median house values now sit above the million dollar mark”.

EXT. Daytime.

A tall, athletic gentleman with a leopard strides down Oxford Street, occasionally invading people’s body space to sign well-wishers on the forehead and to distribute high-fives, accept gifts and bump fists and such.

He speaks to the reader as he walks.

ME:

In conclusion…

Lots of people got very rich during this pandemic – the upswing in values has generated extraordinary, often obscene wealth for the people who could afford it. Likewise the barriers to entry for the rest of the nation grew beyond most hopes and many fears.

While data out of the ABS and CoreLogic show these massive monthly gains peaked around April last year, the softening monthly gains still stretched the gap further and further.

Now, Eliza says the game is changing again.

CUT TO:

INT. Night.

Eliza Owen, surrounded by whirring machines and complex data banks. Her hair is a mess and it looks like she hasn’t slept. A guard in a CoreLogic branded flak jacket and a concealed Uzi blocks the only exit.

Eliza: (hushed voice, looks around anxiously)

“Arguably, there are more headwinds than tailwinds now stacked against continued growth in the property market, with the potential for sooner than expected cash rate increases, affordability constraints, and weakening consumer sentiment slowing demand.

“While some structural shifts through the pandemic, such as remote work, may sustain demand in regional Australia long term, it’s likely housing values will start to decline – on a fairly broad basis – later this year.”

Fades to black.

Fin.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.