Think Big: How Australia ranks in the post-COVID policy transition to clean energy

Europe, the UK and Canada are leading the way on clean energy in the post-COVID recovery. (Pic: Getty)

When the global economy was ground a complete halt by COVID-19, it wasn’t a bad thing for the planet (at least for a few months).

With international travel ruled out (and lots of domestic travel too), global carbon emissions fell by the highest level since 1990.

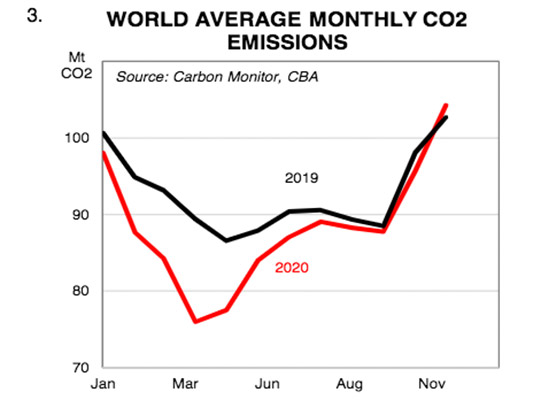

This chart from Commonwealth Bank, using data from Carbon Monitor, shows the extent of the decline:

The equally striking thing about that chart though is that as soon as July last year, global CO2 emissions were back at 2019 levels.

CBA analyst Carol Kong said a similar thing happened after the 2008 financial crisis, when the slowdown in economic activity reduced emissions before picking up again – aided by plenty of policy stimulus.

Kong said a key feature of the post-GFC recovery was that stimulus measures were deployed in support of carbon intensive industries.

“For example, fossil fuel subsidies were 15 times higher than the amount spent on clean energy in the post-GFC period,” Kong said.

But this time, governments globally have an opportunity to deploy stimulus measures that help to further advance the progress of clean energy solutions.

Kong said the historic levels of government stimulus deployed globally now tops $US13tn.

Plenty of that has still been allocated towards carbon-intensive industries, most notably the aviation sector which required plenty of help to stay afloat.

According to data from Energy Policy Tracker, stimulus commitments to fossil fuel sectors still made up around 50 per cent of support measures in the energy industry.

But it’s better than 15x (in the wake of the GFC). And in addition, “we are seeing some countries also using the post-COVID rebuild period as a opportunity to enhance green priorities”, Kong said.

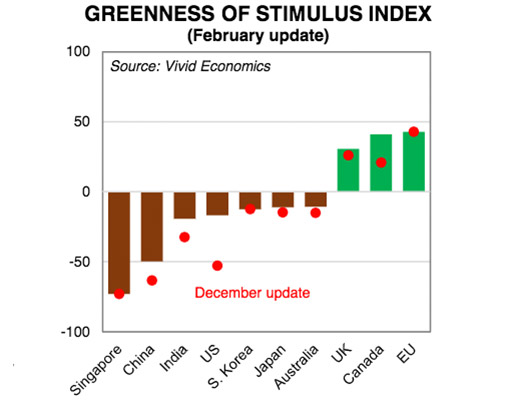

On that front, London-based consultancy firm Vivid Economics put together the Greenness of Stimulus Index (GSI) – a scorecard ranking the extent to which the policy indicatives across major economies have been allocated towards green energy solutions.

Europe tops the list, with Canada and the UK also putting a priority on clean energy in their policy response.

Here’s where Australia sits:

While its initial response was carbon heavy, the US has been climbing fast and could reach a similar level to Europe if the Biden administration’s $US1.7tn Climate Plan is signed into law, Kong said.

China rebounded the fastest out of the pandemic and is likely to be the only major economy that expanded in 2020.

And while most countries saw their carbon emissions fall by between 5-10 per cent, China’s actually increased.

But on a global level, the response indicates that “green is the new black” in the post-COVID world, Kong said.

That’s reflected by survey data that the number of people in major advanced economies who think climate change is a genuine threat has steadily climbed to new record highs over the past eight years.

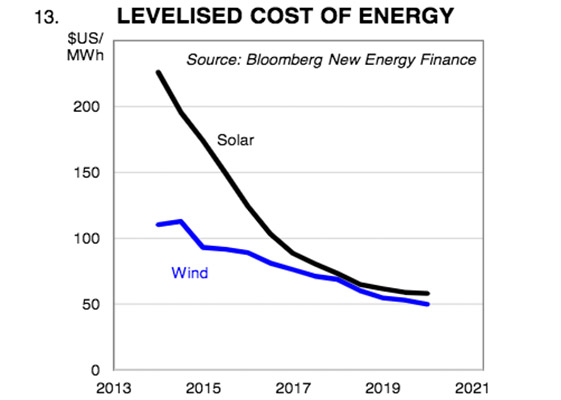

In addition, the economics of green energy projects are increasingly starting to stack up.

“As a production input, cheaper renewables can in turn drive down costs of other emerging technologies such as green hydrogen,” Kong said.

Over the long-term, the framework to assess execution on the clean energy transition has broadly been laid out, with most major economies setting a target for net-zero emissions by 2050.

Kong said the transition to a sustainable future will require more structural changes than just policy stimulus.

But the types of industries targeted by policymakers in the post-COVID recovery phase will serve as a useful guide to the world’s commitment to long-term carbon reduction.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.