Think Big: Chicken or the egg? How asset prices interact with the economic growth cycle

(Getty Images)

Picking winners as a small-cap stock investor isn’t a one-dimensional exercise.

Company-specific research is essential to finding stocks with a competitive advantage that can form the basis of 5x or 10x returns.

But as part of an investment framework, it’s also useful to take a step back and look at broader themes that affect the market as a whole. In other words, “Think Big”.

For this piece — the first in a new Stockhead series — we’ve taken a look at the complex set of forces that shape the direction of global interest rates, and how the rates environment also interacts with stock prices.

Almost any experienced investor will tell you that the outlook for interest rates has at least some bearing on how capital flows move into stocks — even for niche small caps which might be a step or two removed from the macro environment.

Why? The reason is that listed companies are valued as a function of the future cashflows they will generate. An investor who buys a given stock doesn’t have the immediate right to all of those future cashflows, so the present value of a stock assumes an implied discount rate.

The discount rate calculation is subjective, and takes into account various factors such as business risk. Another component is the benchmark rate of interest. When rates are low (like right now) the applied discount rate is also lower, which in turns raises the present value of stocks.

While they aren’t the only driver of stock prices, it’s pretty clear that interest rates — and perhaps more importantly the outlook for future rates — are important investment indicators. As an example, we can assess the impact of recent policy shifts by the US Federal Reserve.

In December 2018, the Fed was in a “hiking” cycle; US interest rates stood at 2.25-2.50 per cent, and the expectation was for two more rate hikes in 2019.

But at that point, markets got jumpy. The S&P500 slumped into a bear market — defined as a fall of more 20 per cent or more from 12-month highs.

By March 2019, the Fed had cut its forecast from two rates hikes in 2019 to none at all. Then in June it began cutting rates, followed by two more cuts in September and October. Fast forward to 2020, and US stocks have not only recouped their losses — the S&P500 sits at an all-time high above 3,300 after surging more than 10 per cent in the new year.

Of course, the Fed doesn’t make its decisions based purely on stock prices. In fact, the US Fed has a sole mandate to keep inflation growth between 2-3 per cent (here’s why that’s important for equity markets).

Other inputs such as employment, wage increases and GDP growth are also important. But it’s still useful to assess how changes in interest rates affect capital flows.

Too much of a good thing?

Closer to home, the Reserve Bank of Australia followed suit — cutting rates three times in the second half of the year to a new record low of 0.75 per cent.

In its latest policy announcement, the RBA kept rates on hold and stuck to its optimistic view about the economy, although markets are priced for the central bank to cut rates again later this year.

And RBA Governor Philip Lowe followed up with an interesting speech called “The Year Ahead”, summarising his 2020 outlook for both the domestic and global economy.

Lowe discussed some of the reasons behind stubbornly low inflation in advanced economies, which are contributing to market expectations that rates will stay lower for longer. But he also highlighted the connection between rates and asset prices — with a word of warning.

“One consequence of interest rates being lower for longer is that asset prices have increased as investors discount future returns by less,” Lowe said.

“We do, though, need to remember that it is possible to have too much of a good thing.”

When it comes to how central bank policy settings interact with asset prices, another interesting point to consider is what factors act as a catalyst for the economic cycle.

Back in the 1970s, it was an economic factor — unexpected inflation — that dragged on stock price and economic growth. As a result, the main focus of central bank policy was bringing inflation back under control.

But since then the process has often gone in reverse — unexpected changes in asset prices are the catalyst for economic shocks.

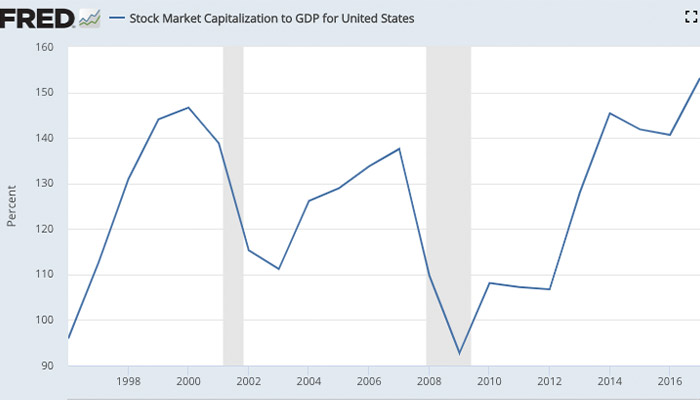

This chart from the St Louis branch of the US Federal Reserve helps illustrate the point:

The blue line accounts for the total market capitalisation of US stocks as a percentage of US GDP, while the two shaded areas represent US recessions.

Since 1996, the line has fallen sharply on two occasions; the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000 followed by the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008.

The GFC was particularly severe, when a slump in some US housing markets sparked a chain reaction which froze up the global economy and sent stocks into free-fall.

What’s clear is that falls in the value of stocks (relative to GDP) preceded the last two economic downturns. In other words they were recession catalysts, rather than the by-product of a slowing economy.

Lowe said the effect of low rates on asset prices is something global policy makers are “keeping a close eye on”.

Those sentiments were a direct echo of Fed Chair Jerome Powell last week, who said the US central bank has been monitoring the run-up in stock prices and commercial debt for “more than a year”.

With the current bull market now the longest in history, policy makers are doing their best to monitor market structures for signs of distress.

But almost by definition, if and when the next economic shock arrives, there’s a good chance it will come from an unexpected downturn in asset prices that very few saw coming.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.