‘UNPRECEDENTED’: The global shipping crisis could take years to unwind… and here’s why Australia could be hardest hit

The grounding of the Ever Given was just an entree to the global shipping crisis. Picture: Getty Images

‘Unprecedented’, ‘abnormal’ and ‘astronomical’. Those are some of the phrases that have been used to describe the post-Covid global shipping crisis, which has seen container shipping rates quadruple since the start of the year.

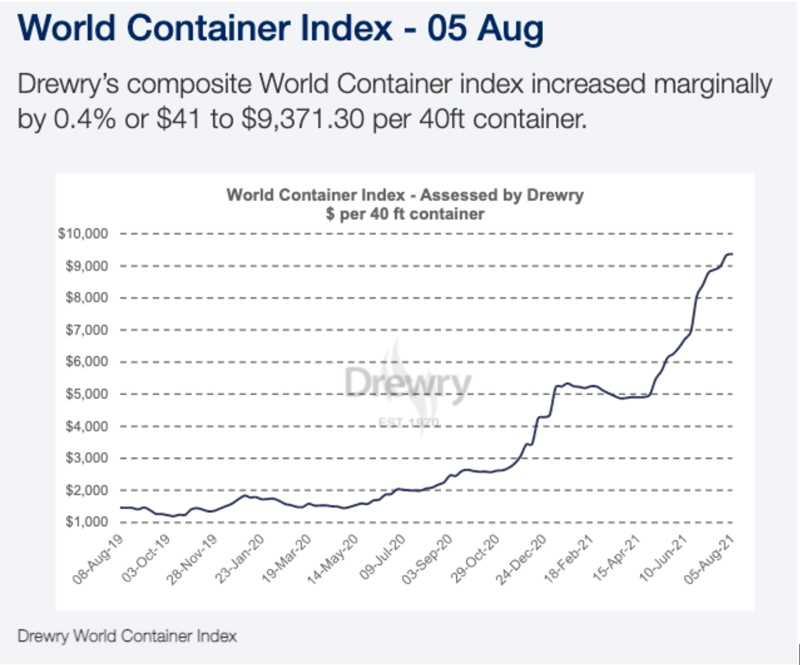

Take any freight index and it will show you just how expensive it has gotten to send a 40ft container from one end of the world to the other.

The Drewry World Container Index for instance has seen prices climb 370% to US$9371.30 a day per 40 foot container. And that’s an average.

Freight rates from Shanghai to Rotterdam and Shanghai to New York on the spot market are up around US$13,500 a day, and anecdotally rates can be as high as US$25,000 on those trade lanes.

A day.

And experts say it could be 2023 before we start to see the fundamental causes of 2021’s maritime trade bubble unwind.

Prices like these could cause inflation and more but rising freight rates are not just about cost pressures for importers and higher prices at your local Red Dot store. They are distorting the very nature of the global container shipping trade, and Australian importers and exporters could be among the losers in the wash up.

So how did we get here, and what does it mean for the Australian economy?

The roots of the global shipping crisis

In 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic began, shipping lines were not great investments.

Take Danish shipper Maersk for instance, which in 2019 reported a US$44 million loss. But in Q2 of 2021 alone, Maersk generated a profit of US$3.7 billion, up an incredible 10.4 times on the US$359 million profit it booked in the second quarter of 2020.

Two years ago skint shippers and pure tonnage providers – companies that lease ships to the shipping lines – did not order new ship builds as they looked to conserve cash.

Covid shut down economies, hammered consumer spending and idled ship fleets, but the massive stimulus packages that followed – mainly from the debt-spiralling USA – had a sudden and marked effect as trade lanes reopened amid a shortage of vessels.

“We foresee the current crunch to need perhaps 12 months to unwind, simply due to those many factors that are now close to the limit,” Copenhagen-based analyst Peter Sand from BIMCO told Stockhead.

“Whatever index you go by, whether it be the Drewry index, be it Shanghai shipping exchange or Xeneta, or Freightos, they are all extraordinarily elevated at the moment.

“You can see it going back to 2019 and even the early days of 2020, that rates not only on the spot market but also on the contract market have risen substantially.”

In America demand for containerised goods has risen as much as 40%.

Sand said that’s “due to the fiscal stimulus provided to American consumers”.

“And they have just not stopped buying containerised goods from far east Asia since they got money on their hands,” he said.

“That crunch in particular is on the Trans-Pacific trade lane where we have seen demand grow almost 40% compared to pre-pandemic levels.”

While European demand has only risen 3%, Sand said, the demand rush in America has seen the cost of freight on the major Asia to Europe lane from Shanghai to Rotterdam soar as well.

That route was impacted also by the delays caused earlier in the year when the Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal.

Freight rates from China to Australia have soared as well, but are cheaper than levels being paid by importers in North America and Europe. And that is a big problem.

Back of the line

As container rates run hot on the world’s most popular trade lanes, increasingly ships which previously ran the routes from Shanghai to places like Australia, Africa, New Zealand and South America are being placed on more favourable routes.

“Some liner companies have actually opened up an extra trade on the Trans-Pacific, and if need be they have closed down another lane where those ships simply do not call to port anymore,” Sand said.

“Even though we see high freight rates across the board at the moment, demand growth is very located in the Trans-Pacific.”

According to Brett Charlton, Tasmanian general manager for logistics firm Agility, that puts ports like Australia’s at the back of the line.

Charlton, chairman of the Tasmanian Logistics Committee and a member of the reference panel for the National Supply Chain and Freight Strategy, said it was getting harder to get imported goods to Australia.

“It’s not uncommon to hear of a 40-foot container from Shanghai to Los Angeles to be around US$25,000 freight. Even then you’re still struggling to get that space and people are paying for it, they need to get it,” he said.

“In Australia at the moment prices are around US$8000-9000 to the east coast of Australia. That’s where they’ve landed but they’re probably going up, in fact they were going up US$1000 per container on the 1st of August.

“At the moment shipping lines are increasing rates at a quantum of US$300-500 for a 20ft container – double that for a 40ft container – every 14 days.

“If you put yourself in the minds of the shipping lines you have another issue and this is not just the price, this is the capacity to be able to service the market.

“If you’re a shipping company executive in Australia and you’re speaking to your contemporary over in Shanghai and say ‘I need 1000 containers for the next two weeks’, the person in Shanghai, from the same shipping line, is saying ‘how much revenue are you getting for each of those containers?’”

That is where it gets tricky for the Australian executives.

“The guy down here is saying $8000 a container,” Charlton said. “This guy in China is saying ‘why would I release my containers to you when I can get $25,000 a container to America or to Europe?’

“So there’s a real struggle internally with the shipping lines to justify an equipment request and there’s a real equipment deficit at the moment in China.

“We’ve got some cargo that’s been waiting there since May to get a ship because we can’t get a container or a spot.”

Shippers under pressure to push the bottom line

Remember those pure tonnage providers we mentioned earlier?

They are another reason shippers are going to prioritise higher routes. According to Sand and Charlton virtually every ship that can be deployed is deployed at the moment.

It is still not enough.

“I think of course in terms of profitability certainly the container ship liners (are the winners) and also who we call pure tonnage providers, those who own the ships,” Sand said.

“They went from hell to heaven from one year ago to right now. One year ago those tonnage providers issued statements where they would run out of cash.

“Today they are re-letting their ships at record high charter rates. Even old skints, ships that burn an enormous amount of fuel when compared to an efficient modern ship.”

Charlton said this will put pressure on major shipping lines like Denmark’s Maersk, Switzerland’s MSC, France’s CMA ACM, Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd and China’s Cosco to chase higher value trade lanes like the Trans-Pacific and Europe.

“We’re seeing massive delays and massive costs coming down the line. But there’s more risk because the shipping lines themselves are getting increased costs,” he said. “The shipping lines only own a portion of their fleets and the rest are chartered by shipowners predominantly based in Europe.

“I heard of a story where one of the ships, I won’t name the line because it was given to me in confidence. I think it was about a 9000TEU ship, so it carries 9000 (20ft) containers and it was on the run from China to Australia.

“That charter agreement between the shipping line and charter owner runs out (in August) and the charter owner has said … that ship was in 2019 chartered for around $10,000 a day for a period of 12 months.

“Now the people that own the business are saying $50,000/day and you have to commit for three years.

“So it’s not difficult to understand basic economics: If you’re a shipping company and you say it’s going to cost me $50000 a day to have that ship and the freight rates are only $8000/day, that ship will be lost to the Australian market.

“It will go and be redeployed back up to the Asia-US and Asia-Europe trades where they’re getting $25,000/day.”

Running on empties

Because some routes are so much more profitable than others at the moment, shippers are ferrying more air around the world than ever before.

As Charlton explains, this is an issue for exporters. Under normal rate conditions, containers imported into Australia are filled with Aussie exports on the return leg, which in turn helps the shipper cover their costs.

But when prices and demand are so biased towards other routes, getting the empties back to Yantian or another Chinese port as quickly as possible is the number one priority.

“The flipside of this is it affects exporters as well, because containers for here are used for export back out,” Charlton said.

“So at the moment where I am in Tasmania it’s hand to mouth. We are constantly trying to find containers for our exporters to export out.

“And the bizarre thing is demand is high. People want our agriculture, they want our aluminium, they want our zinc, they want our Mondelez milks and cheeses.

“I’m just talking about Tasmania.”

While a ship’s capacity is measured in container units, the reality is it can only carry so much weight.

“A ship may be able to carry 8000 containers, but if 5000 of those containers are really heavy that’s all you can carry because it’s a ship on water,” Charlton said.

“At the moment a 20ft freight rate from here to Shanghai is only around US$650, it’s not that expensive.

“But if that container weighs 27t, they can get effectively 13 empty containers on that ship.

“So rather than have that container full of export going back to China, they’d rather say we won’t carry any full cargo, we’ll just get our empty containers back because as soon as we get those back they can be redeployed into the Asia-US, Asia Europe trade.”

Door shutting on some export destinations

According to Charlton, some shipping lines have cancelled routes to less profitable or more logistically challenging destinations like the Middle East and India so they can service the priority Europe and US trade lanes.

“We’ve got a container to go to New Delhi that’s ready next week and not one shipping line can tell me when they can take it,” Charlton said. “They’ve got no interest in having that container going from here to India.

“So when you hear AUSTRADE or someone else saying we need to diversify our exports away from China, that’s lovely, but the shipping lines don’t want those containers anywhere near those places.

“They want it back in China so they can get their containers back there and out to ports. So if we’ve got trade issues with China, which we have, it’s a double whammy.”

The container situation has been exacerbated by cost cutting that saw shippers order less containers to service new build ships before Covid hit.

“Even though container manufacturers have been building rapidly over the past year or so, the vacuum is still there,” Sand said.

“We used to go by a multiplier of three, when a shipowner ordered a new ship, say a 5000TEU ship, he ordered 15,000TEUs (15,000 20ft or 7500 40ft containers) of empties to go with that ship.

“But cutting costs and seeing some economies of scale moving into this, when you buy a new ship today you only buy twice as many empties. So that extra number of containers that was always around a decade ago or even five years ago, was not there anymore.

“Container manufacturers are producing whatever they can, there are only a few around so they are busy, but there’s a massive gap between a multiplier of say two boxes per shipping capacity and three as it once was.”

Congestion and blockages

With just about every container ship in the world out on the high seas, shipping lanes and ports are facing unprecedented levels of delays and congestion, which is adding to issues for importers.

That is even before bottlenecks from the Ever Given incident, Covid outbreaks at major ports including Yiantan and industrial action between Australian wharfies and port terminal operators are taken into account.

Many ports too are being impacted by labour shortages or are not set up to deal with the volume of trade demand currently being driven by international stimulus spending.

“Down here for instance in the business I run, we manage all the logistics for the fishery manufacturers for the salmon farms,” Charlton said.

“Two large multinationals have got $55-65 million plants that make fish feed for the salmon industry here and also export to New Zealand.

“You can’t get protein sources from Australia to equal what they currently get from overseas, so they have to bring them in. Sometimes it’s 20 or 30 containers at a time depending on the formula.”

That product, Charlton said, comes primarily from Peru.

“In Peru there’s no equipment,” he said. “There’s more empties in different places rather than where they need to be.

“The trans-shipment port from South America to here is so congested that the shipping line, being MSC, has redirected those containers via Europe.

“So what’s traditionally a 55 day transit time is now 90 days, so they need to account into their supply chain an additional 40 days.

“There’s a piece of 40 days where that hasn’t been accounted for because it’s happened so suddenly, so there’s a real situation where some of these raw materials just aren’t going to be available to make those sorts of products.

“You hear those stories quite regularly.”

Port issues in Australia during periods of industrial action could also see shippers redirect ships to less lucrative but logistically faster lanes.

“There’s no shortage of disruptions that if you’re a shipping executive in Geneva, sipping on a wee dram on a Chesterfield in front of the fire, and you go ‘OK where am I going to deploy my assets’, Australia is at the bottom of the list,” Charlton said.

“We’re not ticking many boxes at the moment.

“We haven’t got the freight rates to rival Asia-Europe, Asia-America. We have a longer type transit, 17 days, so the equipment is being utilised for a longer period of time than the inter-Asia trade.

“So the freight rates may be cheaper between China and Malaysia, but that ship can do three voyages compared to one voyage down to here, so they get triple the revenue.”

Further headwinds could be faced with sources in the logistics industry saying international airliners are looking to pull out of commercial air routes which double as freight lines for produce like salmon, prawns and lobster.

That situation has emerged as stricter arrival caps, imposed by Canberra following Covid outbreaks out of hotel quarantine, have obliterated the financial viability of international passenger flights.

While some perishable goods are exported on charter planes under the government’s IFAM program, most exports are too bulky to be exported via plane, and passenger flights are the main carriers of air freight.

How long will the global shipping crisis take to unwind?

According to Sand, BIMCO does not see any easing in the supply-demand crunch until the latter half of next year.

When exactly the 12 months unwinding period predicted by BIMCO will start is unclear.

“We already for a couple of months have said that 12 months from now we may see somewhat of a normalised market,” Sand said. “I think that 12 months is still ahead of us to the extent that what we have seen in those previous two months has been still an escalation of those supply chain dynamics.

“That’s not working towards an easing of the crunches, it has simply made the supply chain crunches tougher to deal with and that to us explains the most recent hike in freight rates.

“For the shippers it will still be quite costly, at least compared to pre-pandemic levels to ship goods around the world, but for the liner shipping companies it’s certainly windfall profits.”

According to Sand, new-build ship orders are coming in at record levels which could see capacity increase 5-6% in 2023.

“We have seen a record high number of ships being ordered and they will be fed into the global network two years from now predominantly, so we could see 2022 as being lower fleet growth,” he told Stockhead.

“But then we see 2023 arriving at a fleet growth of around 5-6% and that is eventually turning around the crisis right now with the shortage of capacity.

“Eventually that will of course weigh down on freight rates … when shipping capacity again exceeds demand by 2023.”

That is also contingent, however, on slowing consumer demand from America – where Democratic lawmakers are pushing for continued Keynesian-style stimulus measures – and Europe.

That volume of demand is why Charlton is cautious on putting a date on when shipping availability will return to ‘normal’ in Australia.

“We’re really in a difficult spot and as I said before back in 2019 there were no ships being built. It takes about three years for a ship to be built so we’re not seeing the end of this any time soon,” he said.

“Three or four years until those assets become available on the market, and even then those assets are not going to be deployed to our ports, they’re going to be deployed to Europe and America.

“A couple trillion dollars stimulus package in America compared to a couple billion here. It’s amazing we’re actually talking those numbers but you only have to look at the economies of scale.”

Before that? At least two years of Christmas shopping.

“The commentary from the shipping lines is they don’t see any improvement… they don’t even use the word improvement, they don’t see any stabilisation yet,” Charlton said.

“We’ll never see the freight rates go back to those levels is what they’re saying, but they don’t see anything stabilising until mid to maybe Q3 next year at this stage.

“We’re not even in our peak season yet … people are only starting to put their order in for Christmas stock now.

“So there’s going to be lots of sad kids not having red bicycles and Xboxes. If you want to buy your kids’ Christmas presents, get it now.”

NEXT WEEK: Josh Chiat looks at who’s going to be hit hardest – retail or resources?

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.