Private school education or $900k cash? What’s better for your child’s future?

News

News

“If you give a man a fish you feed him for a day. If you teach a man to fish you feed him for a lifetime.” The old proverb is compelling, but does it apply in a world where someone will spend the bulk of the next 30 years paying for their fishing rod and lessons first?

Yes, this is a story about housing affordability. Mostly.

In fact, even the days of 30-year mortgages are under threat. Banks are now mulling 50-year loans just so young people can cope with the high costs of keeping a roof over their head.

This is also a story about how we try to give our kids the best start in life and the true cost of debt. Both of which are key factors in Australia right now as more and more parents sacrifice quality family time to put in more hours at the office, to pay for a private education for their children. The underlying assumption being that a “quality” education – or educational experience – will give those kids a headstart as they jockey for places at university and the job market.

(The bigger question of course is ultimately, is it all about money anyway? But this is not the place to be looking for answers to those type of questions.)

Private school enrolments have grown at their fastest pace in more than a decade. Student debt has risen faster. Housing prices have outstripped both by a soul-destroying margin.

Let’s cut to the chase – is it worth sacrificing that time, energy and money to put your child through an expensive private school, in the hope it will somehow get them ahead of the game?

Or will they be better off with 12 years of public school education, then starting university or their working lives with a chunk of cash? Say, $900,000?

Or more. And yes, we’re well aware this is the kind of angsty dilemma the #FirstWorldProblems hashtag was made for.

Let’s just roll with the charts to start with, then we’ll go into what kind of a monetary advantage buying a purportedly better education can get your kid.

With help from Vanguard Australia we’re looking at how much money can be saved through the value of compounding and annual investment.

The price of school fees varies substantially in Australia and can be a sliding scale from prep to Year 12. Fortunately we have a table to refer to:

It’s only fair to acknowledge that public schooling costs money too. So if you take that away from private costs, the cheapest rate you’ll find is a national average of an extra $4615 a year to send your child to a Catholic metro school ($59,995 for 13 years), an extra $20,425 for an Independent metro school ($265,535 total) and, just for fun, an extra $28,220 for an Independent school in Sydney ($366,860).

So, we wanted to know how much can be earned through an initial investment of each of those sums plus additionally investing them each year for 13 years. We looked at returns across Australian listed property, Australian equities, and US equities based on annual rates of return for each between FY2012 and FY2022.

Our research followed findings by Vanguard that cash was the only equity class to generate a positive return in FY22.

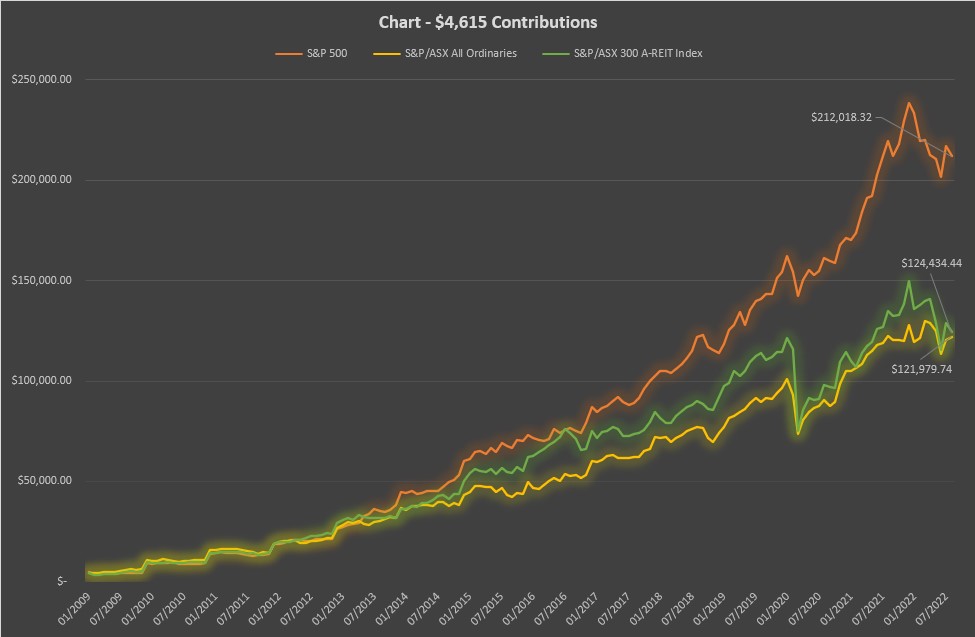

Let’s start with the cheapest rate – $4615 a year to send your child to a Catholic metro school. Let’s see what you get investing that per year for 13 years in the S&P500, S&P/ASX All Ords and the S&PASX300 A-REIT Index:

So your $59,995 investment between 2009 and 2022 got your child either a Catholic school education, or anywhere between $121,979.74 and $212,018.32 cash/shares.

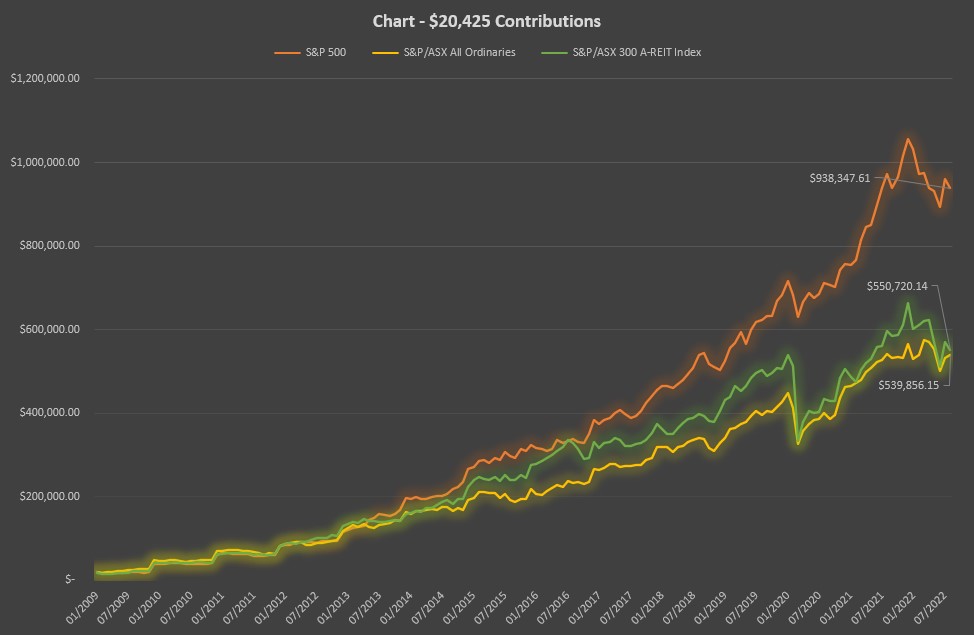

Let’s try it with the national average Independent Metro rate of $20,425 per year ($265,535 total):

Crivens. We’re talking some serious house depositry here. Look at that sweet, sweet S&P500 return of nigh on a million.

You know where this is heading but let’s go with the average Sydney Independent Metro rate of $28,220 ($366,860 total):

Even the All Ords is returning a $750,000 headstart for your precious double-barrel named darling. There’s probably a school for sale somewhere in Australia for the S&P500 return.

And because it’s Australia’s favourite stock, we looked at what investing the same money for a year in CBA stock since 2009 would have returned. But we didn’t go past back of the envelope level, because it was nowhere near as exciting:

And there’s another point to be made about diversification, because we are, after all, a site about investing. So let’s give Vanguard’s Head of Personal Investor Balaji Gopal a quick minute to explain how these kind of returns are not isolated.

“The data from the last decade tells us two things, the first is that diversification is an investor’s best defence,” he said.

“Each of the three asset classes has had a turn at being the best performing, as well as the worst over the 10-year period, which is why we continue to encourage investors to mitigate risk by maintaining a well-balanced, diversified portfolio rather than regularly trying to pick winners. In other words, buy the haystack rather than looking for that elusive needle.

Gopal also would like to note the significance that regular contributions has in on overall investing goals.

“Starting your investing journey is important but adding to your investments at regular intervals and continuing to increase them is equally important, if not more.”

Thank you, Balaji.

Now, to push our point further, what would the kids rather roll the dice on? It’s only fair we break down the other side of the equation – what’s a university degree worth?

And before we go on, a reminder again to save your angry, tearstained tweets. This is purely a financial exercise.

There are no happiness guarantees here, we are not licensed for that.

As an Australian citizen in a Commonwealth Supported Place (CSP) university program a uni student will be left with a hefty Higher Education Loan Program (HELP, formerly HECS) debt for a graduation present.

The costs can set you back anywhere from around $20k for three-year undergraduate degrees to well above $50k for a five-year degree like law, medicine, or engineering.

According to ATO figures in 2021, the average student debt was $23,685. The number of people with debts above $50k has continued to grow, reaching 278,069 (9.6% of all debtors) in 2020–21, up from 256,053 (9.0% of all debtors) in 2019–20. A quarter of people with debts above $50k owe more than $100,001.

So what does that extra few years out of the workforce and debt get you?

In 2019, 52% of 25-34-year-olds in Australia had a tertiary degree, above the OECD average of 45%. Of those, 86% were employed. The rate for those who went to the workforce in their upper secondary years, or post-secondary non-tertiary, was 81%.

So not a huge difference there. Either way, you’ll get a job if you really want one.

However, according to figures, having a degree also carries a considerable earnings advantage in most OECD and partner countries. In Australia, in 2018, 25-64 year-olds with a tertiary degree with income from full-time, full-year employment earned 25% more than full-time, full-year workers with upper secondary education compared to 54% on average across OECD countries.

The ABS estimates average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time adults in Australia increased by 1.9% to $1,769.80 annually to May 2022.

So 25% on top of that $92,029.60 is a tidy $23,000 a year. Suddenly, over a 40-year working life, it’s looking a bit like that debt and extra years out of the workforce for uni might be worth chasing.

Okay. Now for the controversial bit. Does sending your kid to a private school give them a better chance at getting to – and through – university?

According to ABS stats private school enrolments have grown at their fastest pace in more than a decade. Schools data reveal a 2.6% growth in full time equivalent enrolments being the sector’s highest since 2008.

But going a step further, does a private education necessarily buy your child a higher ATAR? It’s hard to get a proper finger on that pulse and private versus public schooling is an emotional issue. So much so that a lot, almost all, in fact, of reporting on research is in some ways clouded by ideological positioning.

There’s always talk about taking into consideration socioeconomic backgrounds, and lots of “adjustments” being made for various factors.

But the fact is the numbers, hard stats, say yes, private school education generally results in higher ATAR scores.

Sorry if that offends you. We can’t change it.

So let’s try to put this into a little perspective. Paying for private school provides your child a better chance to get to uni, which gives them a slightly higher chance of getting employment and that employment will pay 25% more. Over 40 years, somewhere nudging $1 million at today’s dollarbucks-worth.

Now, the reason we’re here. Is that 25% more in your child’s pay packet for the next 40 years a better option – financially – than starting their working life with anywhere between $121,000 and more than $1.296 million in their hand?

Remember the average Australian full-time worker is earning $1,769.80 a week. The extra 25% is around $23,000 per annum. And the average HELP debt to pay back is $23,685.

Now, keep in mind they’ll be out of the fulltime workforce for at least three years while getting that degree.

In a 2019-20 Pre-Budget white paper, the National Union of Students put the average annual earnings of Australian students at $18,300. Over three years, that equates to $54,900. But in that time, they’re now $276,120 behind in terms of average national wages.

It’s going to take your child another 12 years of fulltime work before the extra money they earn from their degree pulls back that $276,120. After giving away a three-year head start.

House prices don’t discriminate. You can guarantee that in the meantime, they’ll be galloping off into the distance.

This is not financial advice. There’s also the thing about past performance does not guarantee future results. And none of it is certainly of any use to parents who can’t afford private school fees, aside from the fact that it’s ridiculous to even imagine a public school education in any way hinders the ability to gain a place at university.

But for those who can afford private school fees, there’s no denying that all Australia’s children – even the “well off” ones – are facing a wildly different home ownership reality upon leaving secondary school than any generation that has gone before it.

It’s important to have a place of one’s own. Or if not a home, a very healthy seed with which to germinate a business, or rack up several years of travel, or volunteering, or… just not having to worry about money for a couple of years while you sort things out.

Obviously you can’t have this conversation with a child starting prep, but it could be worth having with one who’s heading out of secondary school and fully understands how it feels to be launching into what looks like a lifetime of paying off debt.

What will they choose for their child? Private school – or public and $900,000 to start their adult life?

This story does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.