No, this is a ‘recession play’: Berkshire’s Q3 earnings jump more than 40pc

Picture: Getty Images

Warren Buffett’s business buffet, the conglomerate that is Berkshire Hathaway, dropped its Q3 report over the weekend.

And somehow, despite reporting a net loss of US$12.77 billion, the company’s operating income erupted – surging by 40.65% on the previous Q3 – from $7.65bn to $10.76bn.

So – a big jump in third quarter operating earnings and a record pile of cash-on-the-side is what happens when Warren Buffett just doesn’t see the right conditions for dealmaking opportunities.

Other than snapping up 6 million of US home builder D.R. Horton Inc. (DHI) shares worth some $725 million, Buffett has also built his stake in Occidental Petroleum to over 25%.

WTF, WB!?

I hear you scream into your pillows.

Just what world does WB inhabit where circa US$13bn in losses doesn’t touch the sides?

It’s Warren World. A grown-up world of sensible tempers and big numbers.

This quarter, The Oracle of Omaha didn’t send his usual earnings missive – but that full year letter is on its way for Christmas – and at somewhere around 100 years old, frankly, he doesn’t have to. Instead Berkshire just told investors what Berkshire investors already know – equity portfolio fluctuations are inevitable, meaningless and neccesary.

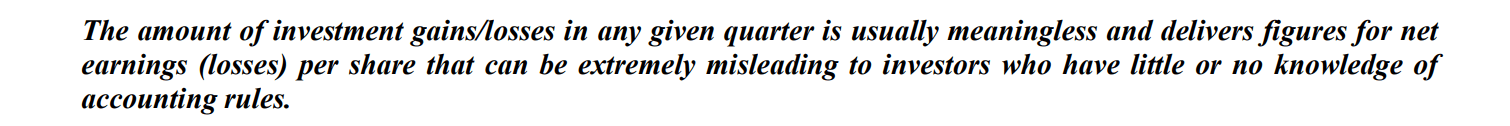

While that’s disappointing from a literary standpoint – they really are great – can you imagine even BHP putting this line (bold/italics) in just after dropping its 4E:

That’s a bit haughty and naughty for a company, but I guess, when your total Q3 investment loss of US$24.1bn is a very large number to the rest of the universe, yet a wee blip of an anomaly in Buffett’s Big Business Breakfast of Life, you can say things which sound stupid coming from the rest of the universe.

Like perhaps this: Buffett’s Two Rules of Investing: “Rule No. 1: Never lose money. Rule No. 2: Never forget rule No.1”.

However, for every glib remark, the Berkshire chair and chief tends to live and invest by the ideas that’ve made him the seventh-richest person in the universe today.

Like this: “Beware the investment activity that produces applause; the great moves are usually greeted by yawns.”

That better captures Buffett’s thinking around the Q3 loss which reflects not just the yank backwards global markets were given in the last quarter, but how tough it was even for Apple (AAPL) which still makes up nearly half the entire Berkshire equity portfolio.

In a rare rough run for the tech giant, Apple stock fell almost 12% during the quarter – hitting Berkshire’s top line.

Buffett did not address shareholders in a letter, but the company said the losses were caused by changes during the third quarter in the unrealised gains that existed in the company’s equity security investment holdings.

The Omaha-based conglomerate’s operating earnings, which are the profits which rain down into the delta that is Berkshire’s topographical map of wholly owned businesses – insurance, transport, infrastructure, railways, industry, utilities — hit a $10.761bn total net for the quarter. That’s a 40.6% increase on the same quarter a year ago.

Cash and Treasure

Berkshire held a record level of cash at the end of September, expanding its grotesque cash hoard to $157.2bn, up from $147.4bn in the second quarter and easily topping the $149.2bn high of Q3 2021.

And where’s the money stashed? Largely in Treasury bills, which recently surged past 5%.

Berkshire increased its Treasury bill holdings by 36% in the last year, which totalled $126bn in Q3.

Berkshire has been capitalising like crazy on the yields that just trounce the take on US consumer inflation (CPI) as record fast-rising interest rates have made the hgher ground of US Treasuries so much more attractive.

The “Oracle of Omaha” has been taking advantage of surging bond yields, buying up short-term Treasury bills yielding at least 5%. The conglomerate owned $126.4 billion worth of such investments at the end of the third quarter, compared to about $93 billion at the end of last year.

Taking back

Buyback activity continued to slow down as Berkshire shares roared to a record high during Q3.

Berkshire splashed some $1.1bn buying back its stock.

WB’s been buying back at leisure, a practice he strongly believes is beneficial to all shareholders.

Stock repurchases have drawn whiny complaints and weak criticism from US politicians who say Corporate America should find a more constructive use of their influence and cash.

They’ve been saying (tweeting mainly) something like – WB. Why give earnings per share a short sharp boost, when investing in the US of A or employees would be more beneficial??

Warren doesn’t buy it

“When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive),” the 92-year-old investor said in February.

Buffett believes buybacks are beneficial to shareholders as they provide a lift to per-share intrinsic value.

“The math isn’t complicated: When the share count goes down, your interest in our many businesses goes up. Every small bit helps if repurchases are made at value-accretive prices. Gains from value-accretive repurchases, it should be emphasised, benefit all owners – in every respect.”

In response to that, Buffett has spent about $7bn betting on himself so far this year; in the third quarter repurchasing more than 145,570 shares of its Class A and Class B stock.

And why not, when Berkshire’s Class A shares have climbed a lazy 13.6% in 2023, clocking an all-time high in September before falling away during the lean run of the last few months.

Berkshire – not entirely unaware of the troubles most ordinary businesses and investors face – did take a moment to acknowledge the tough economic conditions from geopolitical risk to inflationary pressures.

“To varying degrees, our operating businesses have been impacted by government and private sector actions to mitigate the adverse economic effects of the COVID-19 virus and its variants as well as by the development of geopolitical conflicts, supply chain disruptions and government actions to slow inflation.”

Big in Japan

The Oracle of Omaha bought a 5% stake in Japan’s top five trading companies.

This year, as Japan’s stock markets rocketed to 33-year highs, Berkshire disclosed it had in fact doubled down, taking its stakes in each company to an average of more than 8.5%. The US giant still has room to run, as it has previously stated it could eventually raise its stakes of each firm to 9.9%.

The “sogo shosha” trading co’s are specialists in sourcing the raw materials from around the world and shipping them to resources-poor Japan. They focus on diversified long-term investments that prioritise value and cash flow.

A remnant of post-war reconstruction, the sogo shosha business model is uniquely Japanese. Although there are ‘trading companies’ of all sorts about the world, there’s nothing like these sprawling can-do trading giants.

The companies are active across an extraordinary variety of commodities and materials from up and downstream products, foods and supply chain goods, wherein they work both as intermediaries, holding houses and logistical services.

The sogo shosha provide a credit management function and a financial facility, leaning on vast financial resources, while also investing in and taking part in the management of businesses as needed. In this regard they deal not only in hardware but also in software, they’re involved directly in developments from urban redevelopment and social infrastructure development, IT solution implementation services, and matching businesses such as licensing of fashion brands and commercialisation of high-tech patents.

The stocks are all up more than 30% this year.

Shares of Mitsubishi and Marubeni are up circa 50% year to date, with Mitsui up 45%, Itochu up 30% and Sumitomo 39% higher.

Marubeni’s business has more than tripled in market cap since Warren first turned up mid-2020. Shares of Mitsubishi have jumped more than 5x.

Japan’s key indices the Nikkei and Topix are both ahead more than 25%, year-to-date.

Elsewhere with Warren

Buffett’s big stake in Apple equates to around 50% of the Berkshire portfolio and the- 12% loss driven in part by Beijing’s opaque ban on iPhone during the quarter represents a near $20bn paper loss, reversing the near $27 billion win in Q2.

Berkshire’s other major stakes to take a quarterly hit alongside Wall Street’s benchmark index were blue chip names, like Bank of America (BoC) (BAC), and Vanilla Coca-Cola (KO).

In the black column, Berkshire’s US insurance giant (but truly awful podcast advertiser) Geico – often described as the crown jewel of Berkshire’s stupendously sized insurance arm – set the conglomerate’s pace for quarterly revenue, bringing in underwriting earnings of $1.1bn.

Warren’s insurer is already snatching back lost market share after the rise of the NKOTB and well-named Progressive – the new upstart US auto insurance hotshot.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.