Here’s why housing bears can take a chill pill as property prices rise

Pic: d3sign / Moment via Getty Images

Housing bears can take a load off — a forthcoming debt crisis is unlikely, CBA says.

Data from CoreLogic showed prices in every capital city except Melbourne rose in October, with home values in Brisbane, Adelaide, Hobart and Canberra climbing to new record highs.

Like stocks, Aussie real estate has felt the tailwinds from macro policy response to COVID-19.

Interest rates have been slashed to almost zero, reducing mortgage costs and freeing up more people to take out a loan.

And the government has got on board, introducing $25,000 HomeBuilder grants and opening up 10,000 more places for the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme.

The RBA doesn’t expect these rate settings to change for another three years. And competition is heating up in the mortgage sector as lenders battle for market share.

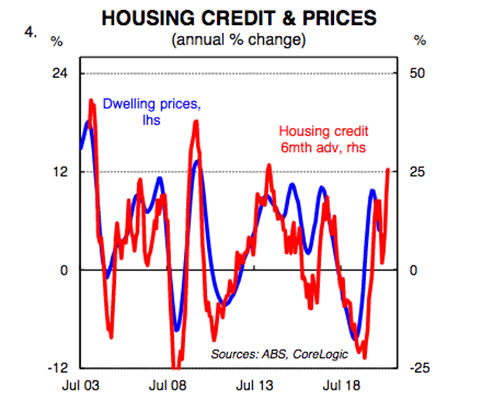

As a result, growth in housing credit is back on the rise.

And as this chart from CBA shows, credit growth has proven to be an accurate leading indicator of house prices:

Looking ahead, CBA’s head of Australian economics Gareth Aird expects house prices to rise faster than household income next year.

And it might not be long before FOMO (fear of missing out) rears its head and more borrowers charge into the market.

“It is a natural response to interest rates going so low,” Aird said.

Housing bears caught unawares

Mortgage risks have always been a talking point in Australia, given the country has one of the highest rates of household debt to disposable income in the world.

Taken in aggregate — record low rates, surging credit growth and rising prices — the current confluence of factors has again raised the spectre of a housing bubble in some circles.

But Aird said in the current environment, it’s not the flow of credit but the stock of credit which matters most.

“The stock of household debt is simply all of the outstanding credit to the household sector,” he explained.

And when it comes to financial stability, it’s the overall stock of debt that policy makers will be more focused on.

To illustrate the recent contrast in flow and stock, Aird said ABS data showed growth in new lending in September ripped higher by 25 per cent in annual terms.

However, the overall stock of credit only rose by 3.3pc for owner/occupiers, and fell by 0.4pc for housing investors.

Why? Debt repayments.

New loans to owner-occupiers aren’t giving rise to a surge in overall debt because “”many households are using lower interest rates to accelerate debt repayment”, Aird said.

Worthy of note for housing bears is that Australia’s rate of household debt to disposable income peaked in Q2 2019.

That’s also just before the RBA cut the benchmark cash rate last June, after leaving it at 1.5pc for almost three years.

And Aird says the trend should to continue into next year.

“Whilst we expect record low interest rates to drive new lending higher, we believe the majority of households will use the lower rates to accelerate debt repayment,” he said.

The view is backed up by CBA’s own data which showed that as at June 2020, 65pc of home loan customers were ahead on repayments, and around one third of borrowers had a two-year buffer.

At the same time, COVID-19 has given rise to some marked changes in Australia’s consumer outlook.

Westpac’s consumer confidence index is sitting at seven-year highs, while the household savings rate has surged amidst all the social mobility restrictions.

But while Aussie households have some cash to splash, Aird doesn’t reckon they’re itching to leverage up on mortgage debt.

“We still think that indebted households as a collective will retain the mindset to use lower rates as an opportunity to accelerate debt repayment,” he said.

In turn, Australia’s debt ratio will edger higher before settling below its previous peak at around 185-190 per cent of disposable income.

“As such, rising home prices and a lift in new lending do not pose a risk to financial stability in 2021.”

By extension, the RBA is unlikely to make any policy adjustments based on their housing market next year.

Rather, any changes will be based on the reflective strength of Australia’s broader economy.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.