Breaking down bracket creep and other tax torments I have known

News

The Albanese Government’s decision to revamp the Stage 3 tax cuts has stirred up a hornet’s nest.

And since nothing really concentrates the mind like pain, we can thank the Australian Government’s changes for refocussing attention on the urgent need for tax reform.

They said the wouldn’t – but Albo et al’s move to cut benefits for higher income earners (with those on $200,000 or more getting $4546 a year less) and redistribute them to lower and middle-income earners (with those earning between $50,000 and $130,000 now getting $804 a year more) in order to provide cost of living relief – is something that’s at least easy to understand.

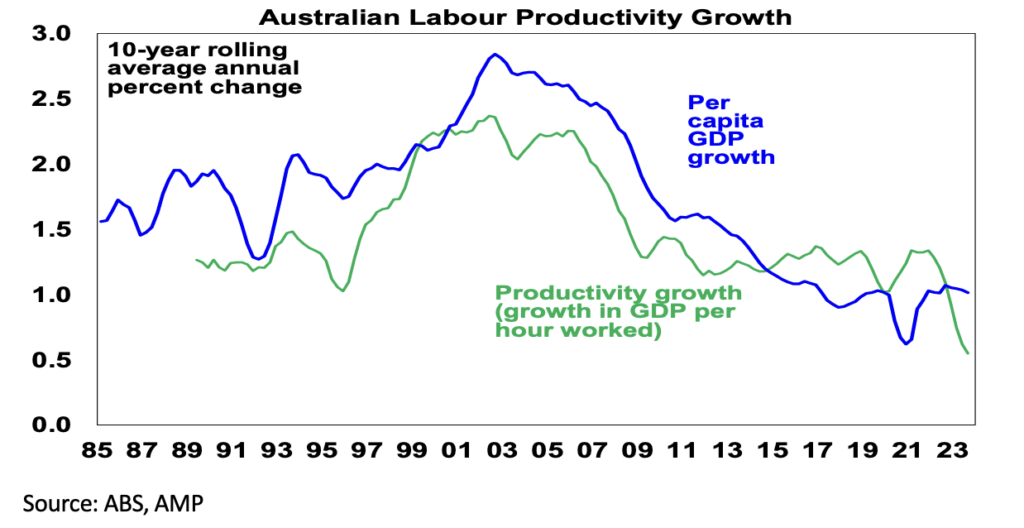

Failure to reform the archaic Aussie tax system – according to Dr Shane Oliver, head of investment strategy and chief economist at AMP – is not just a risk to further damaging essential productivity growth but a threat to the haughty living standards on which we live.

The other problem is tax reform effects everyone, but grasping it by the husk isn’t for everyone.

The arguments for change are a bit more esoteric, Dr Oliver says. But they come down to a local tax system with basically five key problems: it’s heavily reliant on income tax; it’s complicated by numerous tax concessions; it’s highly progressive; it has ongoing “bracket creep”; and it suffers from some good old Aussie anachronisms.

• First, he says, is the politics around committing in the last election and until recently to proceed with the tax cuts as legislated (despite cost of living issues long being well known) only to then break the commitment.

• Second, is the concern that the move treats the symptoms and not the causes of high inflation and risks backfiring. This is because by skewing them to low- and middle-income earners who consume a higher proportion of their income runs the risk that it will add to demand and hence inflation. This risks delaying interest rate cuts.

• And finally, is the argument that it’s yet another backward step in terms of tax reform. This is critical as in recent years Australia’s productivity performance has deteriorated.

“This has driven a slump in growth in per capita GDP which means lower than otherwise living standards.”

“To boost productivity growth we need to do a bunch of things … but a key thing is to reform our tax system.

“The Stage 3 tax cuts were a step in that direction because they reduced the issue of bracket creep (where taxpayers jump into higher tax brackets never intended for them just by seeing average wages growth).

“It did this by having one flat 30% tax rate for earnings between $45,000 & $200,000.

“They were also part of a three-stage process with the first two focussed on low and middle income earners.. The Stage 3 tax changes unravel this modest reform.”

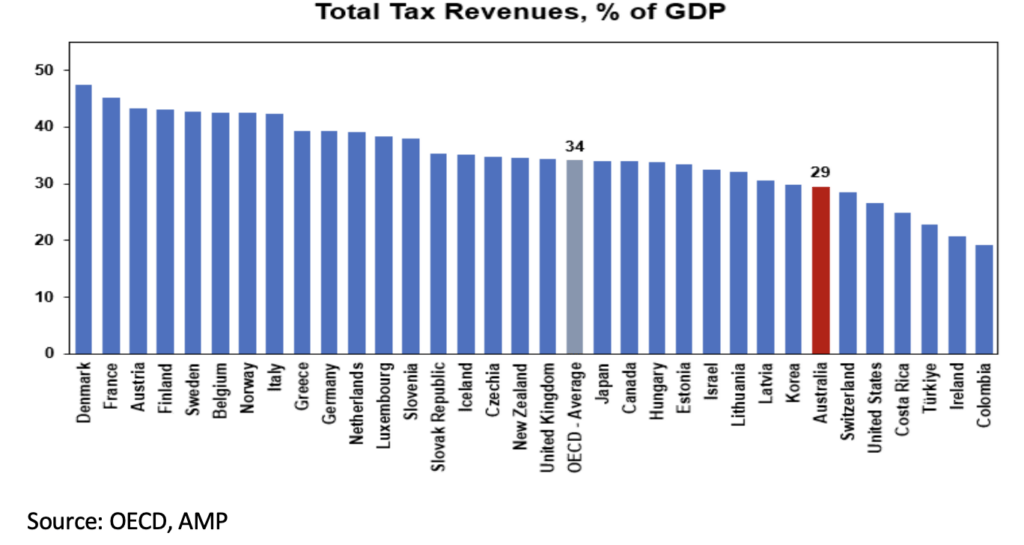

The good news is Australia is a relatively low-tax country.

As per Shane’s table below, our total tax revenue as a share of GDP at 29% in 2022 was at the low end of OECD countries.

“The complication is that this does not tell the whole picture because it doesn’t include superannuation contributions. If adjustment is made for this then we are likely more in the middle of the pack.”

More fundamentally, Shane told Stockhead, there are five key issues with our tax system, and here they are with conveniently identifiable hashtags…

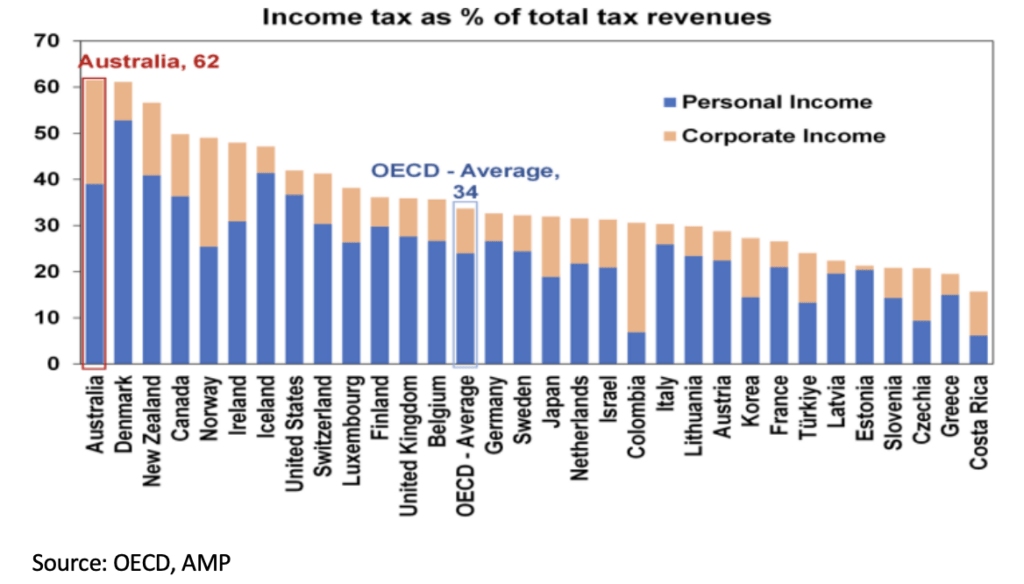

Income tax is 62% of tax collections vs the OECD average of 34%, according to AMP research.

The problem with this is that income tax is highly distortionary – ‘cos it impacts decisions to work and invest – whereas a GST levied at the same rate on all items is far less distortionary.

“So a GST is a far more efficient tax than income tax and a greater reliance on it versus income tax will likely lead to more productivity.

“The high reliance on income tax will also create equity issues as the aging population will see an increasing burden placed on younger workers to foot rising health and aged care bills.”

Of course, Dr Oliver says, the GST is also more regressive – hitting lower income earners harder, but this can be addressed by the setting of the tax scales and compensation.

Several “tax concessions” are often in the headlines: enter Messrs Negative Gearing, the Capital Gains tax discount, Franking Credits, Superannuation and Trusts.

“The arguments put up for curtailing them are that they cost the government revenue, create distortions in the tax system and that the benefits fall mainly to high earners,” Shane says.

But the good doctor adds it’s actually a little more complicated:

Negative gearing

“Negative gearing arises due to the way the tax system works in allowing deductions for expenses incurred in earning income.

“Removing or curtailing it for property investment as some want will create a distortion as it will still be available for investment in other assets,” he says.

“What’s more, negative gearing is not the reason housing affordability is poor and removing or curtailing it could make the situation worse by reducing the supply of rental property.

“Finally, while the dollar value of negative gearing rises with income the majority of taxpayers that negatively gear property are middle-income earners. That said there may be a case for curtailing excessive use of this tax concession.”

Capital gains discount

The capital gains tax discount allows Aussie investors to halve their taxable capital gain on an asset if they hold it for more than a year. It’s not onerous (that’s my observation, not the actual economist in this story.)

“The discount does appear excessive though and it provides an inducement to earn income as a capital gain as it’s taxed at half the rate. So there is a case to consider removing the capital gains tax discount and return to the pre-1999 approach of adjusting capital gains for price inflation,” Oliver says.

Franking credits

“Dividend imputation is a sensible concession that removes a bias against equities by removing the double taxation of earnings – once in the hands of companies and in the hands of investors as dividends.”

Therefore, Shane says, it puts shares onto a level footing with corporate debt.

“It reduces the incentive of firms to excessively rely on debt and encourages firms to pay decent dividends as opposed to hoarding earnings.”

In short, Australia: Curtailing dividend imputation would be “a big mistake.”

Super

Shane says the case for super tax concessions to remain is strong in terms of boosting savings, supporting a large pool of patient capital, providing for self-funding in retirement and reducing reliance on the pension.

Take from this what you will – but the message is that all these calls to end or curtail the various tax concessions need to be assessed in the context of the whole tax system in Australia.

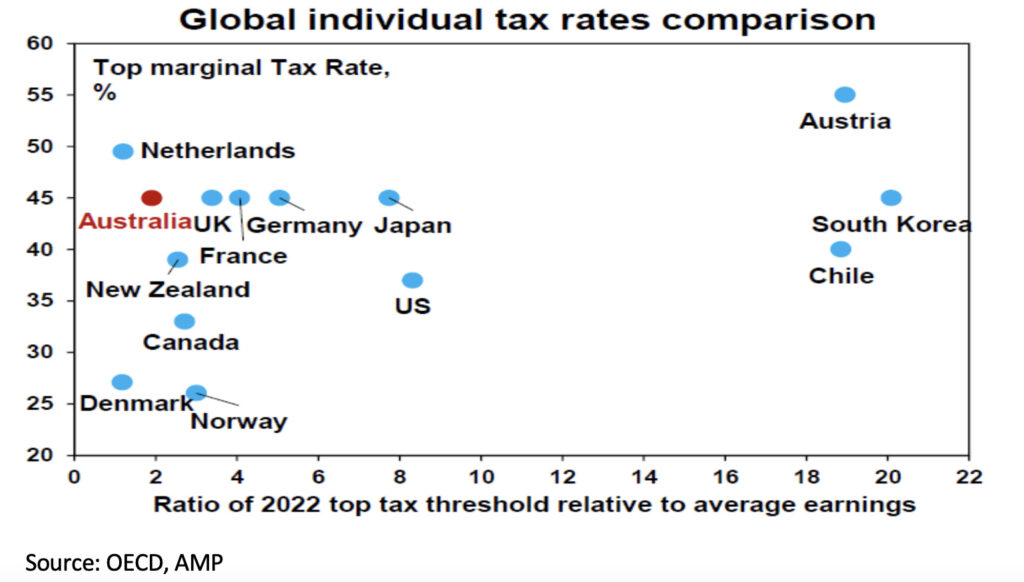

“In this regard, not only does the Australian tax system have a high reliance on income tax but it is highly progressive.”

The current top marginal tax rate at 47% (including Medicare) is above the median of comparable countries and kicks in at a relatively low multiple of average weekly earnings.

So what is this progressiveness?

“Australia’s individual tax system is highly progressive and this is reflected in the fact that the top 3.6% of taxpayers earning more than $180,000 pay around 32% of income tax and the top 10% pay nearly 50% of income tax.”

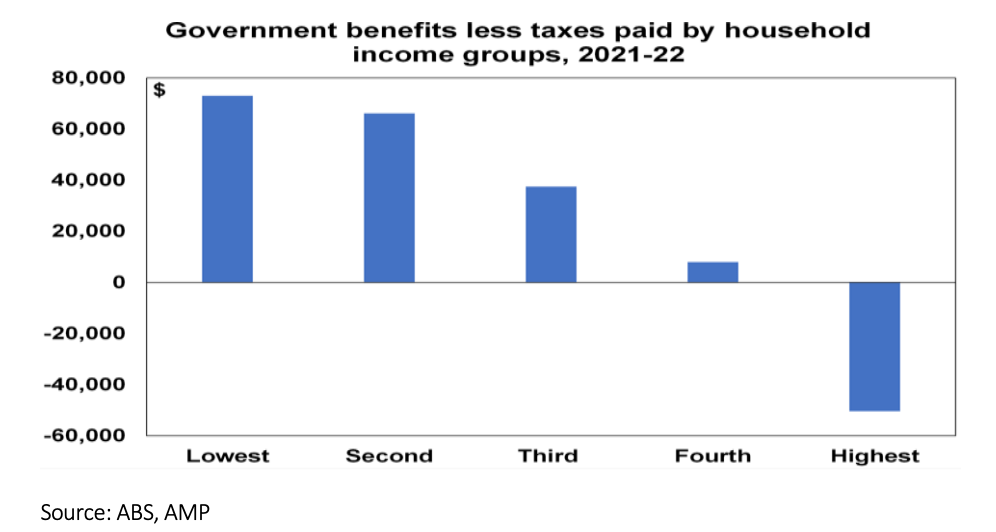

ABS data also indicates that only the top 20% of income earners pay more tax than they receive in government transfers.

“This is likely working against Australia’s long-term interest to the extent that it discourages work effort and hence productivity.”

“Curtailing access to any or all of the “tax concessions” will only add to the burden on this relatively small group and act as a disincentive for work effort at a time when we should be doing the opposite.

“Ideally, we should be looking to reduce the reliance on income tax,” Shane says. “If we did this the interest in strategies like negative gearing would likely decline.”

Just keeping up with inflation can see a worker pushed into a tax bracket that was never intended for them, Dr Oliver says.

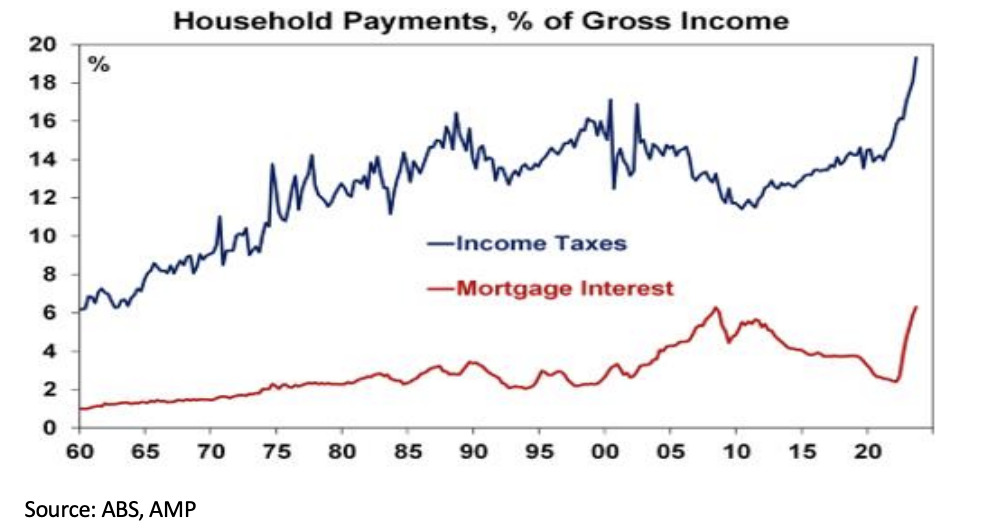

“Bracket creep has been a major contributor to the rise in income tax payments as a share of household income to a record level.

“Over the last two years increasing tax payments have been more of a drag on income than higher mortgage payments.”

The ideal solution he says is to index the tax brackets to inflation.

“This would keep the Government accountable by denying them the ability to give back bracket creep and claim it’s a tax cut and force them to pass higher tax rates through Parliament if they want more tax revenue.”

Key issues is short are that: the GST applies to a diminishing share of consumer spending; states’ stamp duties grossly distort property decisions and worsen housing affordability and should be replaced with land tax; state payroll taxes discourage employment; car tariffs are still levied when there is no car industry to protect; and road user charges need to replace fuel excise to avoid a diminishing share of road users paying for roads.

“What is needed by way of tax reform is simple: lower personal tax rates with higher thresholds; a lower corporate tax rate; a higher and more comprehensive GST; compensation of low income earners and welfare recipients for increasing the GST; the indexation of tax brackets to inflation; and the removal of stamp duty & its replacement with land tax.

“This would take political courage as seen a generation ago.

“But failure to do so will only hamper productivity and living standards for all Australians.”