Bond yields: It’s lift, Jim… but not as we know it

Don't beam me up. Pic via Getty Images

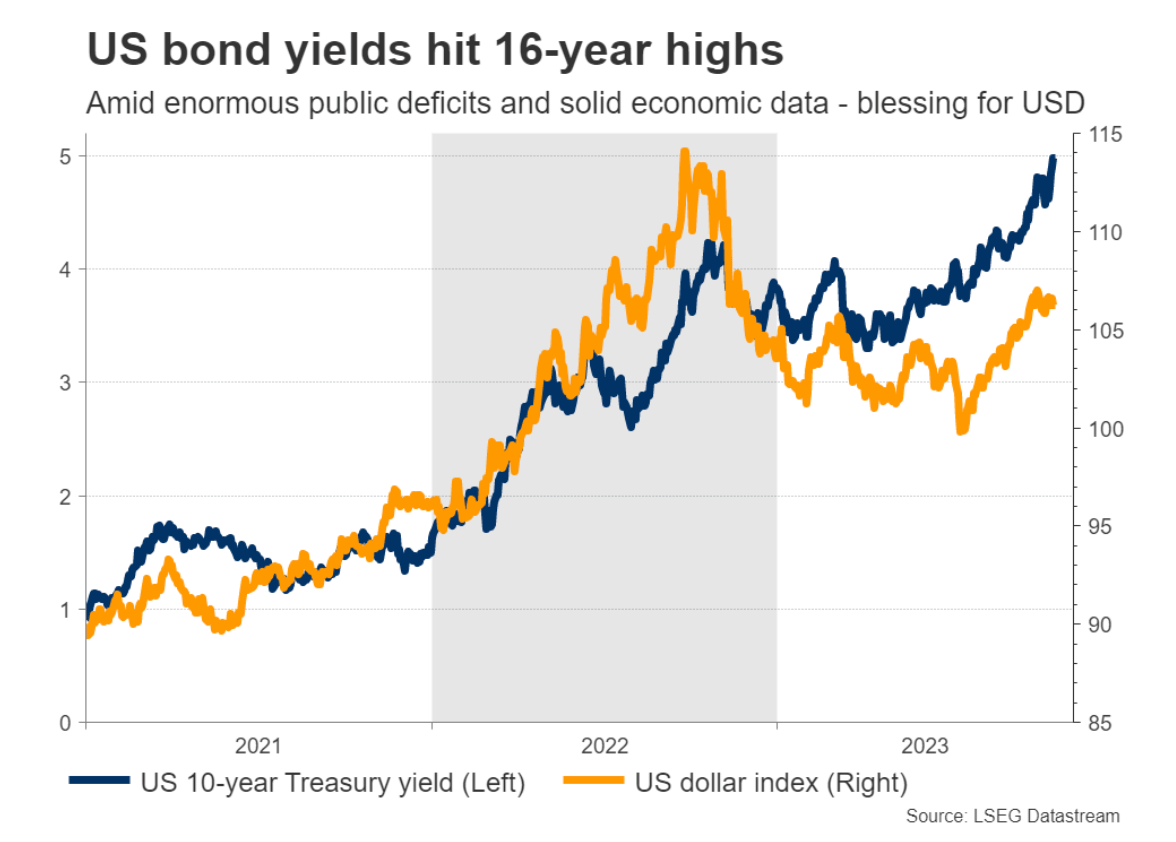

Last week was a momentous one for global markets with US bond yields again making the a spirited ascent – this time jumping 30 points in the space of a week.

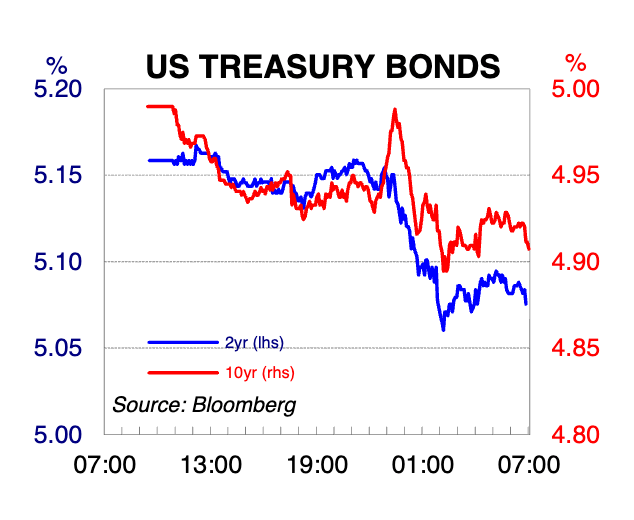

We even saw the US government bond yield take a step back on Friday, when the 10-year Treasury yield gave back 7 points (to 4.91%) after nudging 5.001% late on Thursday in New York for the first time since July 2007.

US Government bond yields have literally soared like a bold, bald eagle since September as a party bag of fears coalesce around worries that the US Federal Reserve (da Fed), the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the European Central Bank (ECB) will all decide to maintain the rage on their hiking cycle and current record high ‘higher for longer’ interest rates.

The US 10-year has now surpassed 5%, something that’s not happened for many, many years – certainly not since the Cambrian explosion, when marine life began to diversify into the seafood buffets’ of today.

That’s changing a lot of things across financial markets.

An example – one might’ve noted the US dollar’s recent return to muscularity – according to XM Australia’s CEO Peter McGuire, that’s been fuelled by a combo of resilient US economic fundamentals, the vacuum of any viable options FX traders and the catapulting rise in US bond yields. These are factors all making the US dollar a reliably attractive investment destination and upending the calculations of central banks and investors everywhere.

So… What’s a bond yield?

Since we’re getting a little scientific it’s worth going through the evolutionary theory behind bonds and such.

First up – a bond is a loan made by an investor to a borrower for a set period of time in return for regular interest payments.

The time from when the bond is issued to when the borrower has agreed to pay back the loan is called the ‘term to maturity’.

There are government bonds (where a government is the borrower) and corporate bonds (where a business or a bank is the borrower).

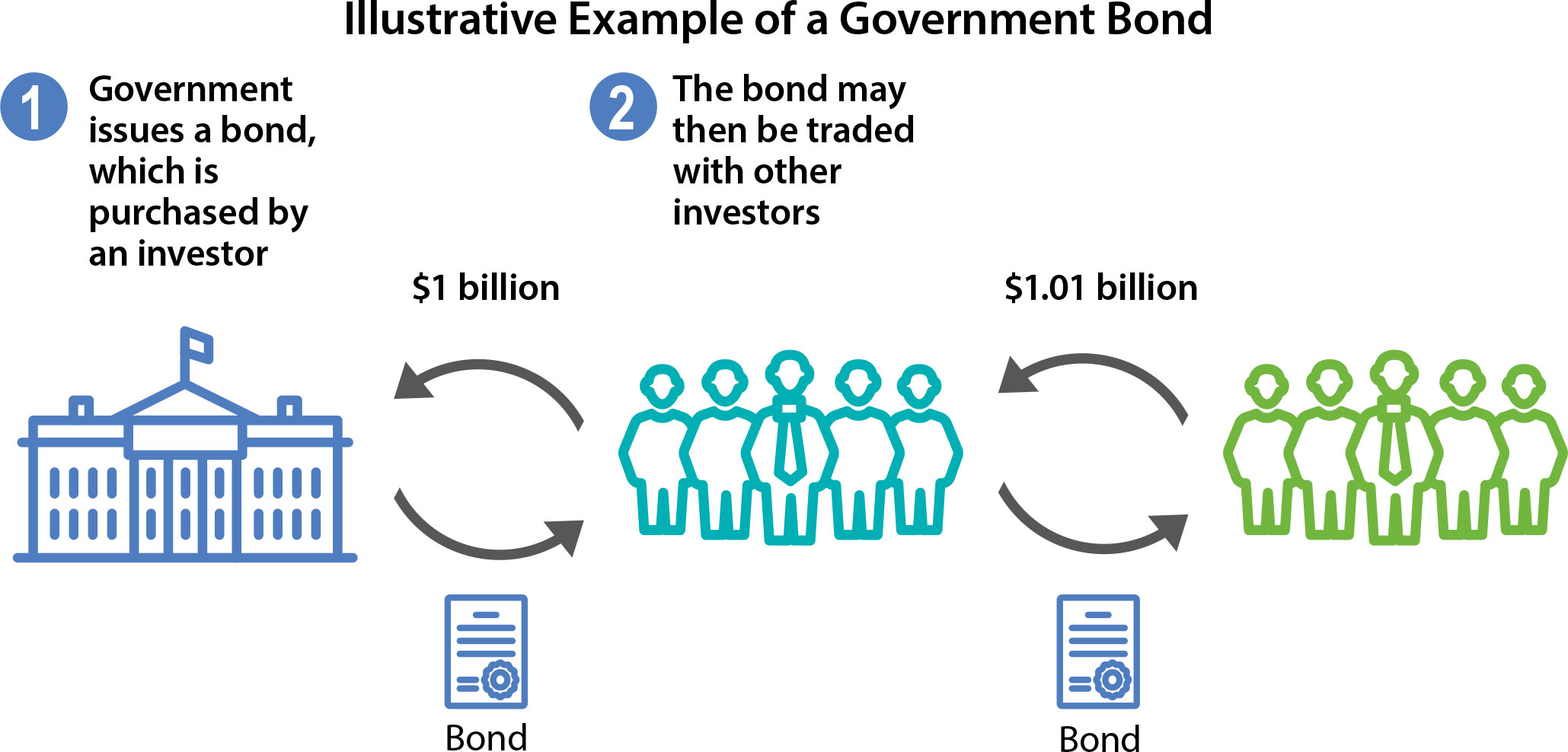

The main diff between a bond and a regular loan is that, once issued, a bond can be traded with other investors and – as a result – a bond at any time also has a market price.

For example, in the RBA’s most excellent pic (below) here’s a fictional Aussie government that has issued a bond to the value of A$1 billion, snapped up by a patriotic investor.

The bond can now be traded with other investors in financial markets, at which point its market price can change (in this instance, it has become $1.01 billion).

A bond’s yield is the return an investor expects to receive each year over its term to maturity.

For the investor who has purchased the bond, the bond yield is a summary of the overall return that accounts for the remaining interest payments and principal they will receive, relative to the price of the bond.

For an issuer of a bond, the bond yield reflects the annual cost of borrowing by issuing a new bond. For example, if the yield on three-year Australian government bonds is 0.25%, this means that it would cost the Australian government 0.25% each year for the next three years to borrow in the bond market by issuing a new three-year bond.

“When a bond is issued, an investor has purchased the bond for the first time in a marketplace called the ‘primary market’.

The initial price the investor pays for the bond depends on a number of factors, including the size of the interest payments promised, the term of the bond and the price of similar bonds already issued into the market.

This information (including the price paid) is used to calculate the initial yield on the bond.

Once a bond is issued, the investor is then able to trade that bond with other investors in the ‘secondary market’ and its price and yield may change with market conditions.”

– The Reserve Bank of Australia

What is the relationship between the price of a bond and its yield?

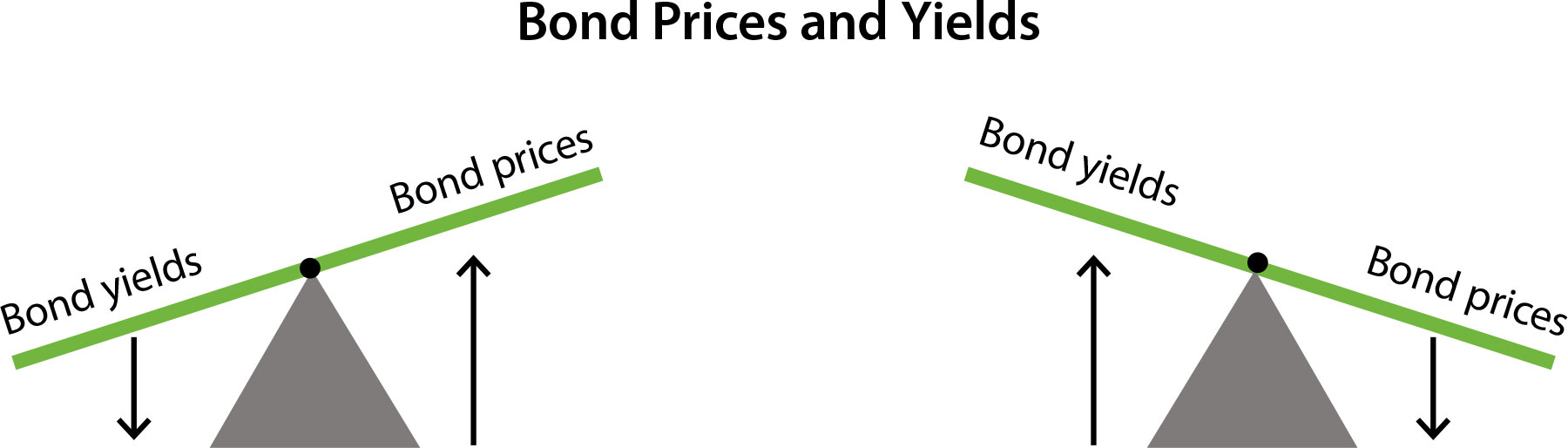

The prices at which investors buy and sell bonds in the secondary market move in the opposite direction to the yields they expect to receive because once a bond is issued, it offers fixed interest payments to its owner over its term to maturity, which doesn’t change.

However, as we’ve been reminded, interest rates in financial markets change (up or down, but mainly up in this instance) and, as a result, newly issued bonds will offer different interest payments to investors than existing bonds.

For example, it’s not easy – but let’s imagine interest rates were to… fall.

New bonds issued would, in this case, offer lower interest payments. This makes existing bonds issued before the fall in interest rates more valuable to investors, because they offer higher interest payments compared to new bonds.

As a result, the price of existing bonds will increase.

However, if a bond’s price increases it is now more expensive for a potential new investor to buy. The bond’s yield will then fall because the return an investor expects from purchasing this bond is now lower. Or should be.

The aggressive sell off in US bonds has prompted speculation that interest rates have adjusted upwards on a structural basis, according to Ninety One investment strategist Russell Silbertson.

Higher forever

During the tempestuous Q3 the yield to maturity on the benchmark 10-year US Treasury Bond exploded upwards – by 0.73% to 4.57% – resulting in a 3.42% loss in the Bloomberg Float Adjusted UST.

The Bloomberg UST Index is a broad-based benchmark, which measures the investment grade, US dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market.

Long-term government bond yields – the risk-free discount rate – have risen at pace perhaps because investors are finally understanding what higher-for-longer actually means. The light at the end of the tunnel is not the end of the tunnel, it’s just a light in the tunnel – and the end of the interest rate cycle is not in the post and may not even have a stamp on it.

Central bankers have done all they can to show that the war on inflation is a no-casualty shock and awe incursion but a long, drawn out war of attrition, where awaiting the outcome is not going to work if markets don’t adjust to the current cash rate levels.

And that’s why yields have continued to agitate in October, too.

Stockhead asked Ninety One investment strategist Russell Silbertson what’s driving the sell-off and where it all might end?

Russell says it’s important to wrap the head around the underlying bits n’ bobs of a bond’s yield.

He says for most major economies with government bonds bearing little or no credit risk, there are just x2 moving parts: the real rate and implied inflation.

Over the September quarter, the implied 10-year inflation rate was little changed, rising from 2.24% to 2.34%.

“Real rates, on the other hand, rose from 1.60% to 2.04% – so bond yields have therefore been rising principally because markets are repricing real yields.”

Russell says look closer and the real rates can be further broken down into global real rates, (a domestic valuation), and a local policy rate.

“The first two factors reflect slow moving factors such as demographics, productivity, and savings on an international and domestic scale respectively. The local policy rate reflects the difference between current policy rates and neutral policy rates, the latter being the so-called r-star.

“The latter is the easiest to understand and the Federal Reserve helpfully provides guidance to both expected official rates and r-star. Over the third quarter, official rate expectations sourced from the Federal Reserve’s Summary of Economic Expectations certainly moved higher, with the median expectation for 2025 standing at 3.9% from 3.4% in June.

Market pricing for the same point in time also moved higher, rising from 3.95% to 4.28%. The Federal Reserve’s assessment of r-star remained unchanged at 2.5%, however.

Given the slow-moving nature of global real rates and the local valuation, Silbertson is ‘sceptical the market can seriously be repricing these based on three months’ worth of economic data.’

The US 2-year Treasury yield dipped 10 points to 5.07%.

The 30 points that the 10-year yield rose by for the week is the highest and fastest climb since April 2022.

“It’s certainly possible these may have changed post-Covid, but we will not know this with any certainty for several years. Rather, it appears that markets have raised their assessment of the local policy rate necessary over the medium term to ensure inflation stays at target.”

Russell says there are two possible explanations for this change of view.

– No. 1: the US’s lax fiscal policy is crowding out other borrowing by huge debt issuance, thus forcing interest rates higher.

– No. 2: Markets are extrapolating the recent resilience of the US economy into medium-term interest rate expectations.

“The paradox here is that, were the US economy to be much firmer than we expect, then tax receipts will be boosted, improving the US’s budget situation.”

More realistically, he says, with monetary policy having only turned tight 6-9 months ago (and now notably so), and given the normal lags involved…

“We would expect the economy to begin to display meaningful signs of economic weakness in the coming quarters, proof that monetary policy is working and so dispel the view the US is in a new paradigm and able to operate at much higher interest rates than it was able to do pre-Covid.”

Cheap, if not cheerful

“We therefore believe government bonds are cheap, and especially so against our medium-term structural valuations, continued the Ninety One investment strategist, adding:

“If the economy begins to weaken, as we fully expect in the months ahead, this valuation gap will begin to close and bonds will rally meaningfully, driven by expectations for the local policy rate.”

ASX Bond ETFs

Yes, there’s an ETF for that.

While one can buy individual bonds directly in the market, Betashares chief economist David Bassannese suggests investors consider what they’re making in the Betashares bond-focused exchange traded funds (ETF) shop.

According to Bassanese, the BetaShares Australian Government Bond ETF (ASX:AGVT) is for those worried about credit risk and the economy falling into a recession.

“The safest duration play would be long duration government bonds, where you take no credit risk. If the economy does slow, credit spreads could widen and that would hurt corporate bonds.

“So if you’re worried about that, you know, AGVT is the standout global Australian bond exposure,” he said.

But if you’re prepared to take on some credit risk, Bassanese recommends the BetaShares Australian Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (ASX:CRED).

“At the moment, credit spreads are still relatively high. But if we have a soft landing, Australian credit spreads could narrow, and you’d benefit from holding the CRED ETF.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.