Australians are flipping their homes at twice the rate ever seen before. And they’re terrible at it

Via Getty

We’re flipping. Yes. Like the American TV shows.

We’re buying houses, we’re hanging around for a short bit and then we’re flipping.

And we’re not good at it.

Certainly that’s my considered and professional takeaway from a raft of new data produced by Eliza Owen and CoreLogic this week.

Eliza says that short-term resales is the new black in a twisted and perverse development in the twisted and perverse Australian property market.

Aside from burgeoning rents due to a structural housing shortage, a record rise in interest rates and a similar, consequent and slightly bizarre rise in most urban housing markets – short-term flipping is Eliza’s new major housing market trend in the back half of 2023.

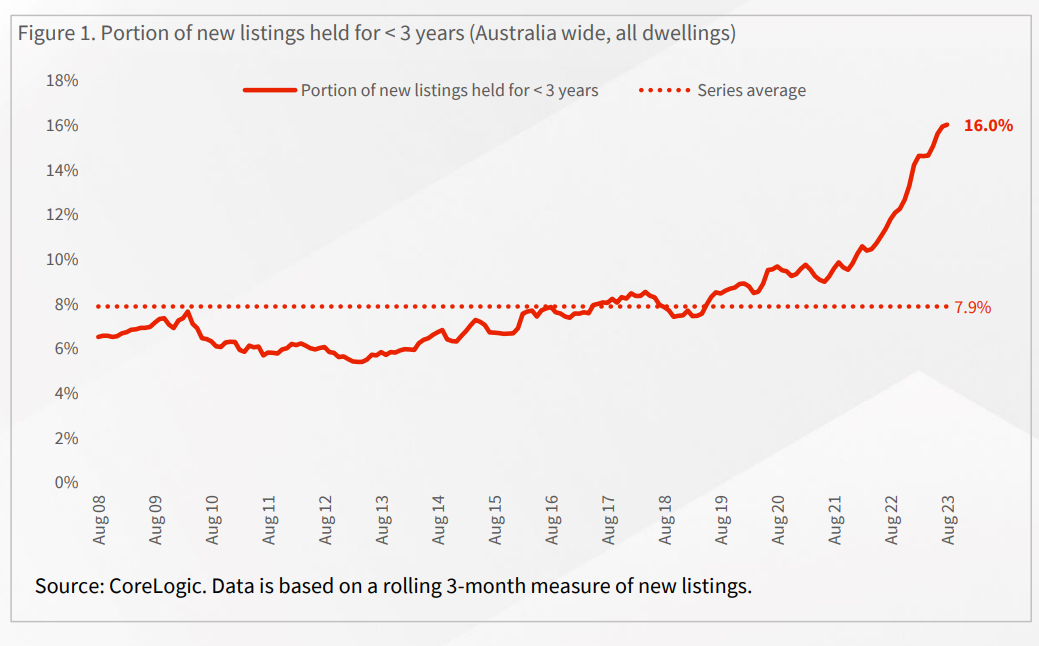

Eliza’s remorseless analysis of fresh data reveals that in the cold dark of Aussie winter, some 16% of total listings that went freshly on to the property market for sale… had been owned for < 3 years.

Eh. We’re not flipping burgers here. It’s not a TV show. So yes – three years is not a long time. That’s a short turnaround – and there’s good reason for why this volume of flipping is twice as much as anything Eliza or CoreLogic’s seen before.

So let’s continue.

Eliza says 16% marks a record high in the big book of Australian property sales, going all the way back to 2008, where the 15-year average of resales within a 3 year time frame is less than half that (7.9%).

The underlying number of new listings held for three years or less also reached a series high of 17,828.

Why are we flipping out, Eliza?

“Short-term resales happen for many reasons, including, yes, people ‘flipping’ homes, looking for large capital gains, or moving for work. Remember COVID?”

I do.

But, Eliza, I’m no good at being noble, but it doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little years don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world – where interest rates have risen with thus rapidity – so, aren’t we looking at an increase in forced sales?

Like, people who borrowed to the hilt and now that the cost of money is so much higher they’re finding themselves caught by the fiscal long-and-curlies.

Yes Christian. Once again you’re spot on.

“Cost of living pressures are high, so resales due to mortgage serviceability constraints may also be a contributor.”

“In fact, the accelerated rise of short-held listings (where the previous sale date was in the past three years), is distinctly noticeable from May 2022, when the underlying cash rate started to move higher from record lows.”

And is this trend same-same all over the country?

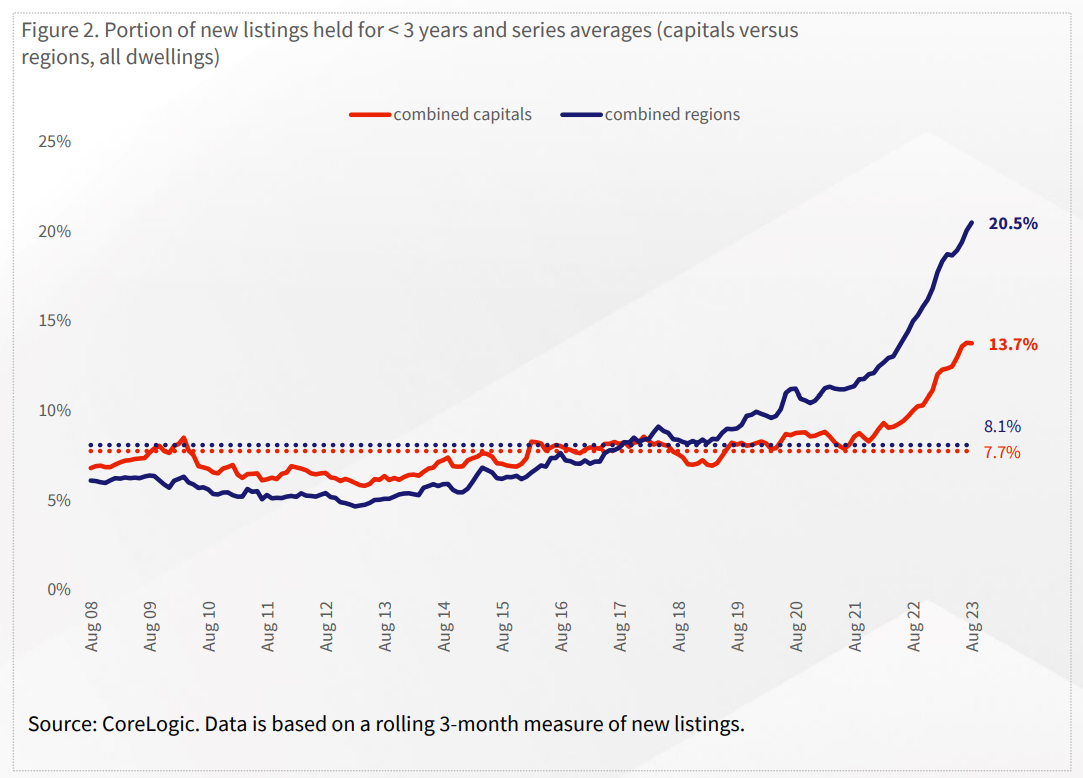

“No. Wrong, wrong – all wrong. I’m seeing a marked difference between the trend in regional Australia and the capital city markets.

“Proportionately, the rise in short-held listings is more pronounced in regional Aussie – where one out of five of every new listing added to the market through winter had only been bought within the past three years (or as early as September 2020),” Eliza says.

The pandemic that ate property trends

So. We’re back to this.

Global pandemic. Quantitive Easing. Walking Dead. Cats and dogs living together.

And fleeing the cities.

“This is an interesting trend to emerge in the context of COVID-19, which was associated with record levels of internal migration to regional Australia,” Eliza says.

From around March 2021, according to the Local Bureau of Numbers, we had a super-spreader event of our own in Aussie real estate.

The ABS data shows that as the virus spread, the volume of city-slickers making for the hills more than doubled.

The total migration to regional Australia from capital cities clocked in at almost 12,000 in the March quarter of that year, up from the previous decade average of circa 5300.

According to Eliza, who’s gone through the latest (provisional) ABS numbers – by March 2023, the tide had entirely turned as net regional migration clocked 5,645 in the same quarter just two years later.

“It is possible that some of the recent departures from regional Australia are some of those who moved to the regions through COVID-19, which may be associated with the sale of a property purchased through the pandemic.

“However, it is worth noting that the rise in short-held new listings was trending higher in regional Australia before the pandemic, from around mid-2019,” Eliza says.

“This was in an environment of falling interest rates and was near the trough of the downturn in regional Australia from 2019.”

Aussie cities flipping out too

Across the capital city markets, Eliza notes, the trend in short-held listings has been broad-based.

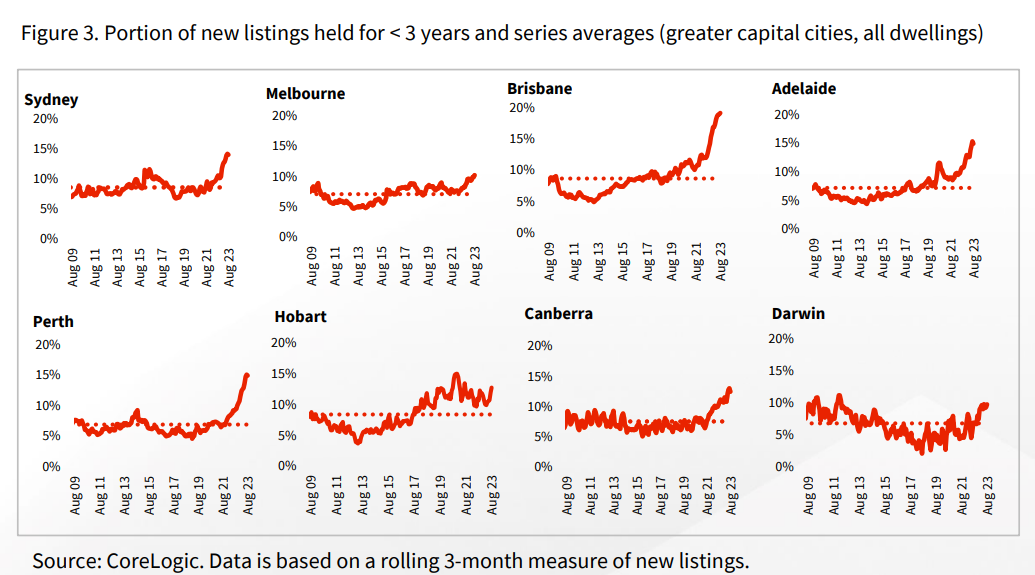

Bris Vegas had the highest concentration of short-held listings through winter, making up an absurd 19.2% of all listings added to the market.

“Interestingly, the rest of Queensland also had the highest portion of the combined regional markets at 23.8%,” Eliza says.

So one in four new homes in regional Queensland was back in the market in under three years.

“Like the broader regional market, southeast Queensland was an exceedingly popular internal migration location through the pandemic*.”

*See the charts below summarise the portion of short-held new listings added to the market on a rolling three-month basis.

“With the exception of Hobart and Darwin, each of the capital cities is showing near-record high proportions of short-held listings coming to market through winter.”

Let’s get granular:

A breakdown of the data at an SA4 level shows the highest concentrations of short-held listings were in:

- Wide Bay (29.6%)

- Cairns (26.2%)

- Gold Coast (25.8%)

I’m not commenting on the net total of disappointed Queensland sea-changing going on here, but in the case of Cairns and Wide Bay, these ridonkulous numbers represent a more than x3 increase on the ‘historic average concentration of new listings held for less than three years.’

It was around x2 for the Gold Coast as well.

Meanwhile, and this is particularly weird – the lowest concentrations were across Melbourne, including:

- Melbourne – Inner (7.0%),

- Melbourne – Outer East (9.6%)

- Melbourne – North East (9.6%)

People dig Melbourne. Bizarre.

Out of 10 how worried should we be about this?

“Housing is typically not an asset that is traded quickly or easily. This is because of high transaction costs (a cost of both time and money) associated with stamp duty, financing, moving and more,” Owen says.

“This can be an inconvenience for the seller, more so if they make a loss from the sale.

“However, the recent phenomenon of short-term reselling is unlikely to result in a loss of broader financial stability, especially while housing market values are rising.

“In fact, periods of strong capital gain can be associated with short-term reselling, because the seller can realise a strong profit which can offset high transactional costs or might be put towards buying a higher-quality property.”

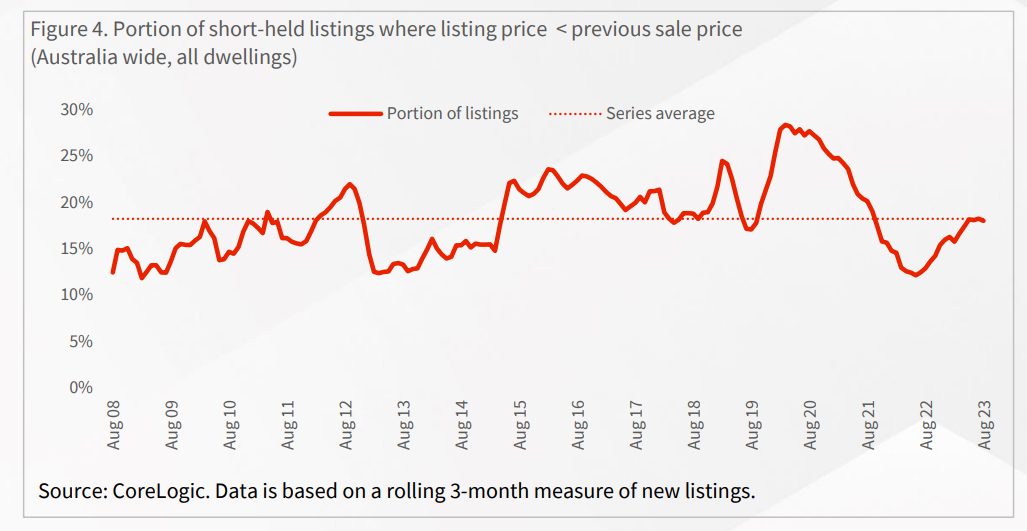

Eliza says Figure 4 – which I’ve dutifully computer-ed onto your screens below – is a useful indicator of whether vendors on short-held properties might expect to sell at a profit or a loss.

“It plots the portion of short-held listings where the advertised price is less than the previous sale price.”

Voila:

A rising phenomenon, but nothing you could bank on

Ms Owen says the portion of properties listed for less than the previous sale price has been rising through 2022, where 9.7% of properties held for two years or less actually sold for a loss.

“The latest listing data indicates that 18% of short-held properties listed were lower than the previous purchase price. But that is lower than the series average (which was 18.2%), and the rate has moved down slightly from the three months to July.”

This all comes back to COVID-19 and the momentary lapse of reason that a good viral pandemic can inspire.

“Interestingly, the recent pain around short-term resales was at the onset of COVID, when 28.3% of vendors who had recently bought listed their property for less in the March 2020 quarter. The underlying number was also higher during that period than through winter 2023.”

So Eliza believes that once you factor in these various extraneous variables – “there might be more to recent short-term sell-offs than high interest rates, and the possibility of falling behind on mortgage payments”.

It’s not entirely the central bank’s fault? That’s annoying.

“Part of this may be a reversal of COVID-related migration trends to the regions, or even the realisation of recent strong gains, particularly in markets across Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia where capital gains have been especially strong despite recent rate rises.”

For these states in particular, Eliza adds, a rise in short-term resales has done little to drive up total listing volumes, and selling conditions remain strong.

But the way out is clear – get the property price machine ticking back over – like it is showing signs of already this spring.

“The more home values rise, as they are expected to in the near term, the more short-term resales are de-risked in terms of servicing outstanding debt.”

Eliza out.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.