Chinese cannabis? It’s complicated…but it’s coming

Pic: Charnchai / iStock / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

In the 19th century, ambitious Brits mused about pushing pianos to one of every five Chinese families, and selling knives and forks to 500 million customers.

In the 20th century, Americans aspired to sell aspirin for a billion headaches and deodorant for two billion armpits.

Today, Chinese cannabis investors are falling prey to similar over-enthusiasm and foreign consultants — if not companies just yet — are wide-eyed at the prospect of selling a little bit of hemp into a huge market.

It’s because while marijuana, the THC-spiked cousin of hemp, is still very illegal, many people are realising that hemp is coming into the light.

How legal? Difficult to say…

Hemp was re-legalised in Yunnan in 2010, followed by Heilongjiang province in 2017. A further five provinces are expected to open up for hemp cultivation by 2020.

China has a long history with marijuana and hemp and the former was a widespread crop in Yunnan. But national authorities intervened and banned the lot after the province became known by backpackers in the 1980s and 90s as a prime spot to get high.

But what is legal and where is still complicated.

Hemp growers require licences, and only a very limited number have as yet been handed out — the latest number Stockhead could find is four in Yunnan, of which one is associated with ASX company Stemcell United (ASX:SCU).

Most hemp is used in textiles or for industrial uses like rope.

Unlike Australia, which has effectively banned CBD or THC nutraceuticals and cosmetics, the China Food and Drug Administration has approved hemp leaf and seeds for cosmetics and for oils, creams, beauty products, and in traditional herbal medicines.

But they aren’t approved as foods or for use in medication, although the Chinese government has started investing in clinical applications around Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis and cancer.

According to cannabis researcher Prohibition Partners, a licence to import products containing hemp-derived CBD is not necessary.

That could open a possible avenue to US hemp growers like Elixinol Global (ASX:EXL), which is facing heavy competition after that market was legalised in December.

Prohibition Partners data shows hemp sales in China were worth $US1.1 billion ($1.6 billion) in 2017 and could be worth as much as $US4.4 billion by 2024.

The country accounts for nearly a third of the global hemp market, according to consultancy New Frontier Data, and hemp-derived CBD accounted for $US53m of sales in 2017 but is forecast to more than quadruple to $US228m by 2020, boosted by demand in China, Japan and South Korea.

Of course there are some ASX companies in there

There are three ASX pot stocks that have relationships with China, and one that thought about it.

Creso Pharma (ASX:CPH) was first, signing a deal in 2017 with Zhejiang Kingdom Creative to import and market its human and animal products in China. At the time Creso said it had opened offices in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

As of this year it doesn’t appear that any sales have been made, as the company said in its annual report in March that its regional operations were in South East Asia and its first full year Asia-Pacific revenue came in at $2,290.

THC Global (ASX:THC) was the next to think about China: the company appointed to the board in January 2018 Steven Xu, a man with connections to China. He promised at the time to put THC in touch with a Yunnan company that produced CBD products and exported to North America.

Then-CEO David Radford said THC didn’t have a China strategy but would consider it in future.

A bruising board fight soon after saw Radford out and Xu elevated to chairman, but medical cannabis-focused THC has so far not made a move on the China connection.

- Subscribe to our daily newsletter

- Join our small cap Facebook group

- Follow us on Facebook or Twitter

Stemcell United is in the business of selling traditional Chinese medicine and has been looking at medical cannabis since early 2017 — even appointing the late industry bad boy, aka “king of cannabis’, Nevil Schoenmakers as an advisor.

But it only zeroed in on China in April 2018, when it did a deal to buy 51 per cent of Yunnan Hua Fang Industrial Hemp (HFIH), conditional on the target getting a hemp licence.

After some scrutiny from the ASX and a long wait for a Chinese hemp licence to plant, sell and process industrial hemp, Stemcell completed the acquisition for RMB3.8m ($794,952) in May this year.

Stemcell says the deal and licence gives it a cannabinoid plant source to use as a stem cell base to research and make cosmetic cannabis products, which can be sold into China via HFIH’s distribution network.

The last ASX pot stock with a China connection is MGC Pharma (ASX:MXC).

The company went via a more “traditional” route for Australian goods in April this year, by partnering with an ecommerce retailer to sell its CBD and hemp nutraceuticals into the Chinese health products market.

Elixinol boss Paul Benhaim told Stockhead in May that people were often approaching the company with opportunities in China, but the challenges meant they weren’t looking at that market yet. Elixinol is operating in Japan.

Investors getting the mania

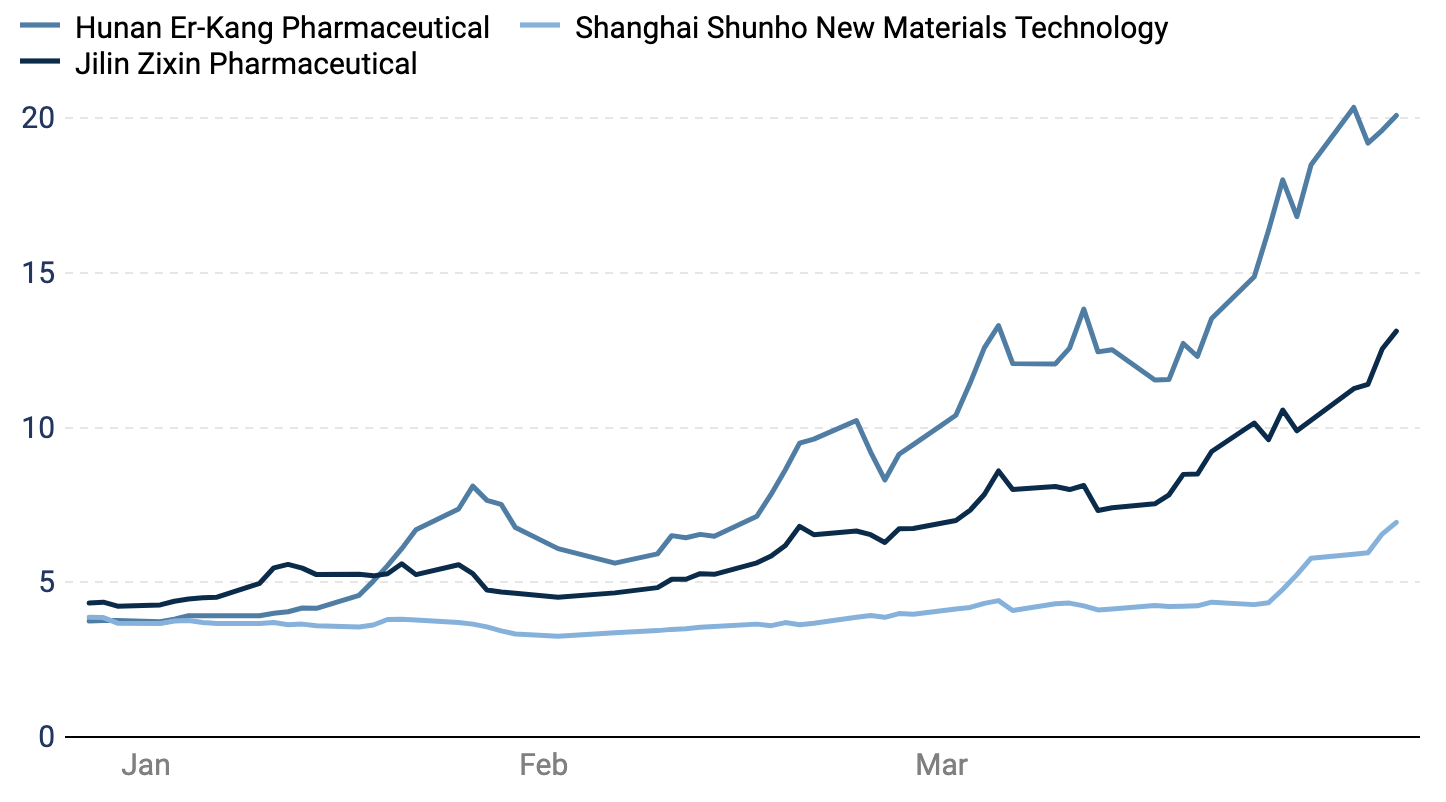

If foreign companies haven’t yet got a sense of the Chinese market, investor mania is booming among Chinese pot stocks.

In March, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange stepped in to halt trading of 20 pot stocks after an exuberant rally this year in any company even tangentially related to cannabis led to a rapid one-day 10 per cent drop.

Chinese markets have circuit breakers, introduced in 2016, that stop trading if stocks or markets drop by a certain amount in order to prevent crashes.

The SSE asked companies including Shanghai Shunho New Materials Technology Co. and Jilin Zixin Pharmaceutical Industrial Co. to update investors on the full nature of their industrial operations and issue a warning on the uncertainties around the sector.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While MGC Pharmaceuticals and Creso Pharma are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.