Can BlinkLab’s autism diagnosis tool replicate the huge success of ResApp?

BlinkLab's app diagnoses autism early through blink reflex analysis. Picture Getty

- BlinkLab’s app diagnoses autism early through blink reflex analysis

- The company is co-founded and chaired by Resapp founder, Brian Leedman

- Stockhead reached out to Leedman to ask him why BlinkLab could be a game changer

Autism is a huge market, affecting 1 in 54 children in the US, with an estimated value of around US$700 billion. Healthcare expenses associated with autism are also on a sharp, steep rise globally.

However, current methods for diagnosing autism often occur late, typically around ages 5-6, missing the crucial early intervention window that is known to significantly improve outcomes for children.

The process is also complicated, and involves input from different experts like psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists. It’s costly, time-consuming, and the diagnostic tools often rely on subjective judgments rather than objective measures.

Enter BlinkLab (ASX:BB1), an exciting new entrant on the ASX, which has emerged as one of the pioneers that could revolutionise these traditional approaches.

BlinkLab was co-founded by current chair Brian Leedman, a serial tech entrepreneur who has carved out a reputation as a visionary in digital health solutions.

His notable ventures include ResApp Health, the former ASX-listed company known for its diagnostic respiratory app which was acquired by Pfizer in 2022 for around $200m.

Leedman explained that autism, as well ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), often present unique challenges in early detection, which can lead to delayed intervention and poorer outcomes.

BlinkLab’s solution? Exploit the power of facial reflexes — specifically blinks — as biomarkers for early detection.

“Imagine using your smartphone’s camera to capture subtle facial responses that indicate neurological conditions,” Leedman told Stockhead.

“It’s a paradigm shift in how we approach diagnosis and intervention.”

How BlinkLab’s technology works

BlinkLab’s smartphone application utilises facial reflexes, specifically how individuals react with blinks to auditory stimuli.

The app captures facial reactions using the phone’s front-facing camera while playing specific sounds or beeps.

By analysing the timing and frequency of blinks and other facial responses, BlinkLab’s technology can provide insights into potential neuro-developmental conditions like autism.

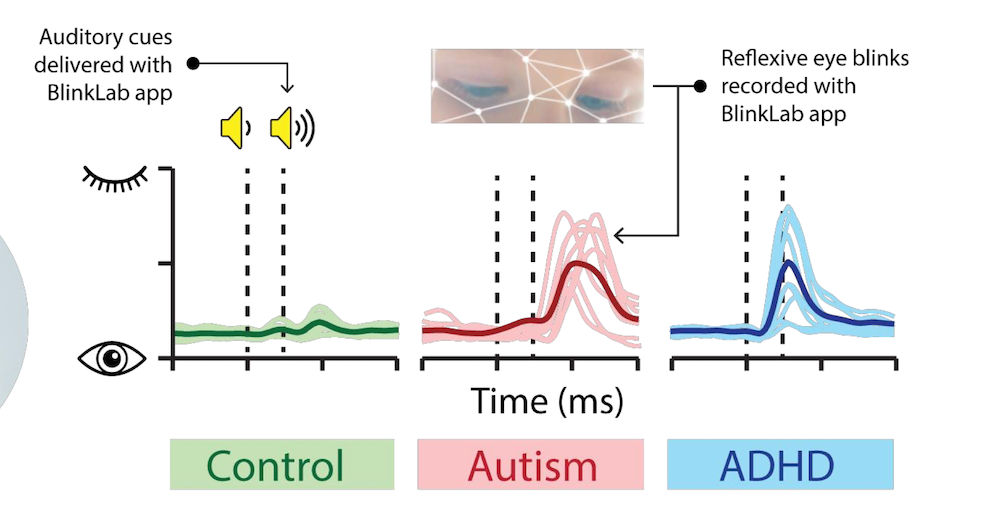

Leedman explained that this method capitalises on the known phenomenon that individuals with autism and ADHD often exhibit different responses to unexpected sounds – such as blinking more frequently or differently compared to neuro-typical individuals.

Research has found that non-autistic individuals often get used to repeated sounds, leading to less blinking over time. In contrast, autistic individuals may continue to blink in response to these sounds, reflecting differences in how they process sensory information.

To assess this theory, researchers had conducted tests using single beep sounds followed by double beep sounds separated only by milliseconds.

The study found that non-autistic individuals generally did not exhibit a blink response to the double beep sounds, indicating their ability to filter out unexpected auditory stimuli.

“But the autistic person, who has a background noise filtering issue and that’s what makes them autistic, can’t filter their environment the way a neurotypical person can, and for whatever reason, they do blink in response this stimuli,” said Leedman.

“This inherent difference was discovered more than 50 years ago, and forms the basis of BlinkLab’s diagnostic technology that was developed and patented by Princeton University.”

According to Leedman, this patent is crucial for attracting investment through licensing agreements or acquisition by larger companies such as major pharmaceutical or tech firms.

“Companies like Apple Health or Google Health are not going to buy or license a technology if it’s not completely patented or protected,” said Leedman.

“And universities are very good at doing that, which is why BlinkLab has a global licence on this research conducted at Princeton for 25 plus years.”

Blinklab also tackles ADHD and potentially, autism spectrum

Blinklab’s platform shows promise not only in autism but also in addressing ADHD, a significantly larger market opportunity due to its broader patient base.

Leedman explained that similar principles of blink response analysis can be applied to differentiate ADHD from autism and neurotypical behaviours.

The app’s ability to measure blink reflex times with high precision, down to a thousandth of a second, is pivotal in distinguishing between these two conditions.

“The time between the stimulus and the blink determines whether the person is autistic or has ADHD. We’re talking about milliseconds here,” said Leedman.

“An autistic person would generally blink first after hearing the stimuli, before the ADHD person does.”

Leedman’s explanation can be seen clearly on the graph below:

In the future, the BlinkLab app could also potentially categorise individuals on the autism spectrum.

“I’m not going to lay claim to this yet. But the research conducted at Princeton indicated that we could not only diagnose autism, but also place the person on the spectrum,” said Leedman.

“That hasn’t been proven yet, but it is clearly something that we would like to focus more funds into because that would be phenomenal,” said Leedman.

Why health devices could be better than drugs for investors

Drawing from his success with ResApp, Leedman highlights the advantages of developing and commercialising digital health applications over traditional drugs.

He explains that traditional drug development is a lengthy, costly, and risky process. It involves several phases of clinical trials, starting with preclinical tests in vitro (test tubes) and in vivo (animal testing), followed by multiple phases of human trials.

These trials, aimed at ensuring safety and efficacy, can take over a decade and cost tens of millions of dollars. The risk is high, as any adverse effects in animals or humans can halt the development process.

In contrast, digital health apps like those developed by BlinkLab and ResApp bypass many of these hurdles.

For instance, ResApp’s technology, which uses a smartphone to diagnose respiratory diseases from the sound of a cough, eliminated the need for extensive safety trials.

“A clinical trial of drugs on humans is all about safety,” Leedman noted.

“But the primary concern for digital health apps is efficacy rather than safety, significantly reducing the time and cost required to reach the market.”

Moreover, digital health apps can quickly generate revenue and gain hospital approval for trials without the stringent safety concerns associated with drugs.

This rapid development cycle allows for a faster commercial outcome, making digital health an appealing sector for investors.

Leedman says the success of ResApp and the promising technology of BlinkLab, which also utilises AI and machine learning, illustrate this enormous potential of digital health apps.

Crucial trials happening in the near term

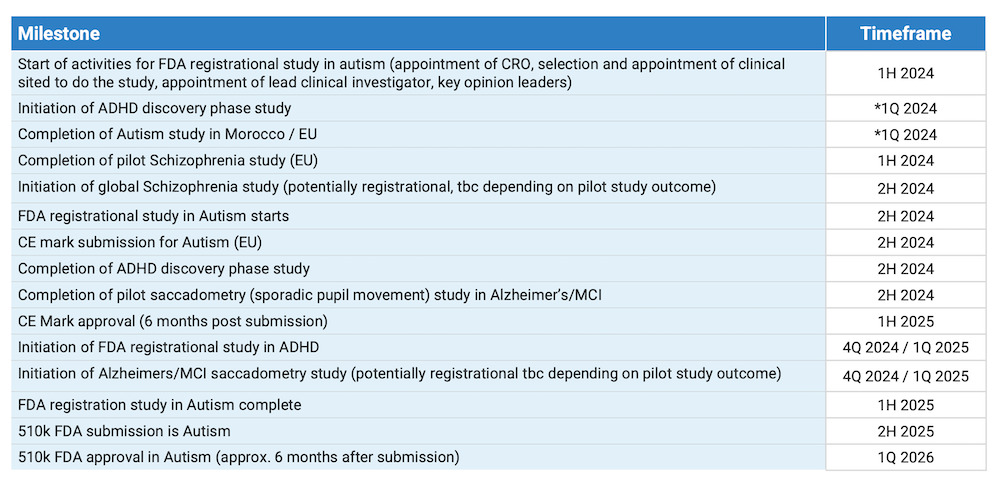

BlinkLab has several near-term catalysts lined up for the latter half of this year.

One of the major upcoming catalysts is the initiation of the FDA registrational study for autism.

Scheduled for commencement in the second half of 2024, this large-scale study will be conducted in partnership with prestigious university hospitals in the United States.

Although the specific institutions have not yet been disclosed, the trial is scheduled to run for a period of 12 months. Results from the trial are then expected in the first quarter of the following year and will be crucial for investors.

Positive outcomes here could pave the way for regulatory approval, making BlinkLab’s technology a frontrunner in the autism diagnostic space.

In addition to the autism trial, BlinkLab is also gearing up for the FDA clinical trial for ADHD, either in Q4 of this year or Q1 of next year.

This trial addresses a significantly larger market than autism, given the higher prevalence of ADHD diagnoses.

The ADHD trial however will follow a similar path to the autism trial, leveraging lessons learned from previous experiences to streamline the process.

Leedman believes BlinkLab’s potential could appeal to both societal needs and investor interests.

“In Australia, the NDIS spends 35% of its funds, its single biggest expenditure, specifically on autism and children. So we’re talking about a huge issue here in this country,” says Leedman.

“Also, investors love to hear about a technology or concept that’s easy to understand.

“I find that that’s certainly what appealed with Resapp, it wasn’t difficult to get your head around the idea of an app that could analyse the sounds of a cough to detect a respiratory disease. Which is why Pfizer ended up buying the company.

“So the value proposition for BlinkLab is pretty similar. We have an app here that can diagnose an autistic or ADHD individual at a very young age.

“Because of that, we can get the best clinical outcome for these children and that’s of massive interest to Big Pharma, because Big Pharma are the ones who develop the drugs to treat these children.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.