Interest rates: How high will they go, and what does it mean for mortgage costs and house prices?

Pic: Getty

- Interest rates in Australia will rise to 1.25% next year, CBA says.

- Markets are priced for this rate hike cycle to top out at 2.5%.

- CBA says house prices will fall ~8% in 2023, and left the door open for sharper rate hikes

Remember 2021? The good old days, when the RBA held firm to its mantra through thick and thin; interest rates won’t rise in Australia until 2024.

No longer, CBA says.

Rates are going up, most likely in June, said CBA’s chief Australian economist Gareth Aird.

Like the US central bank before it, one key question for investors is perhaps less when the RBA will start rising, and more, high how will they need to raise rates?

Last week, we flagged separate CBA research which presented a base case for US rates to top out at 2.5%.

Gazing into his crystal ball for the RBA, Aird reckons Aussie interest rates will start the hike toward 1.25% in June.

CBA’s base case is for the benchmark cash rate to stay there through to year-end, although Aird acknowledged the market is twice as bullish.

Currently, market pricing indicates that interest rates will finish 2023 at 2.50%.

What does it mean for the economy?

A benchmark rate of 1.25% is Aird’s assessment for a ‘neutral’ rate of interest, which is neither expansionary or contractionary to the broader economy.

Will the RBA need to go higher? Despite his base case scenario, Aird is “very open to the idea”.

In effect, the bank’s move to raise rates will be reactionary. Inflation is already above the target band, and the labour market is strong.

“As such, there is a genuine risk that the RBA’s patient approach to normalising the cash rate leads to stronger inflation that is harder to contain,” Aird said.

So it may need to raise rates faster to catch up. But such a scenario isn’t part of CBA’s base case, and the main reason for that is Australia’s housing market.

What does it mean for mortgage rates?

When it comes to the monetary policy lever, Aird said any increase to the cash rate will be “very powerful” in Australia, given the level of household indebtedness.

Before rates started falling again prior to the pandemic in 2019, Australia’s housing debt as a percentage of disposable income was edging lower.

That trend reversed sharply post-COVID as rates were slashed to zero, buyers piled into the market and house prices surged (led by an influx of first-home buyers and owner-occupiers).

“As a result, rate rises will be far more potent that other jurisdictions where households don’t carry as much debt,” Aird said.

From a base of almost zero, each rate rise also marks a much more significant change relative to the benchmark cash rate, he added.

For example, if rates rise by 25 basis points from 0.25% to 0.5%, that’s equivalent to a double-up of the benchmark cash rate.

Comparatively, a 25bp increase on, say, 5%, is a much more incremental difference.

What it means is that “the interest cost on debt goes up very quickly in percentage terms for a given increase in the cash rate”, Aird said.

What that means is the RBA is walking a fine line.

Aird says CBA analysis shows that if the cash rate does reach the market pricing forecast – 2.5% — it will take mortgage payments to “their highest level on record as a percentage of disposable income”.

As a result, the difference between a neutral rate of interest and a contractionary rate is “very, very narrow”, he said.

In addition, CBA’s rates team has flagged that mortgage rates may need to climb slightly faster than the benchmark rate hike cycle, due to an increase in bank funding costs.

For now, changes in lending rates show how banks are preparing for financial conditions to tighten.

Plenty of lenders in Australia are still offering variable mortgage rates at or below 2%.

However, three-year fixed rates are already on the rise. Through most of 2021, three-year fixed loans by the Big Four banks averaged around 2%.

Now, CBA’s website shows its fixed rate on three-year mortgages has jumped to 3.94%.

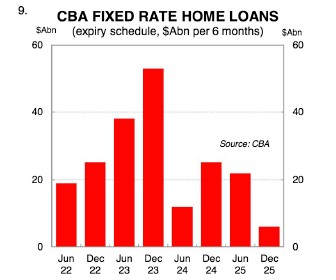

In addition, plenty of existing three-year fixed mortgages will roll over in 2023, following the explosion of new lending that kicked off in 2020.

This chart shows the spike in context, with around $90bn in fixed loans scheduled for refinancing next year:

On the plus side, RBA governor Phil Lowe noted last week that the median Aussie borrower is two years ahead on their mortgage repayments.

But Aird noted that the housing market and Australia’s broader economy are inextricably linked.

More than other advanced economies, a slowdown in Australia’s housing market has a bigger impact on general sentiment and household spending decisions.

Recent data shows a consistent wane in domestic consumer confidence.

“Rising consumer prices and talk of rate hikes will do that,” Aird said.

Following the pandemic boom, CBA expects house price gains to be broadly flat this year, before falling by 8% in 2023, in connection with its base-case for a 1.25% rise in interest rates.

Such a decline can be absorbed by the domestic economy’s broader strength, and isn’t much to worry about, Aird said.

However, an RBA which finds itself playing catch-up on inflation with steeper rate rises towards the 2.5% mark could spark larger house price falls and negatively affect the economy.

“Households are less likely to dig into savings buffers to fund discretionary consumption in an environment of sharply rising rates and falling house prices,” Aird said.

“Such a situation is unwanted and can be avoided.”

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.