The Ethical Investor: Transition Bond – why it could be key to net zero… and can ASX investors trade it?

What is transition bond, and how is it different from a green bond? Picture Getty

- Japan’s issuance of the world’s first ‘transition bond’ could trigger sea of change

- What is transition bond, and how is it different from a green bond?

- How ASX investors can get in on the action

Earlier this week, Japan announced that it will issue the world’s first sovereign Climate Transition Bond aimed at helping the Japanese government fund the country’s shift toward net zero carbon by 2050.

Priced at a yield of 0.74% with a maturity of 10 years, the 800 billion yen (US$5.3 billion) issuance was part of a wider ¥1.6 trillion (US$11 billion) program announced previously by the Japan’s Ministry of Finance.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s office has stated that half of the proceeds will be earmarked for R&D (research and development) on emission reduction technologies, while the other half will be used for green subsidies.

So what is a transition bond, and how does it differ from the green bond?

Transition bonds are often considered as a hybrid between green bonds and sustainability-linked bonds.

As we know, green bonds are linked to pre-identified environmentally friendly projects, such as solar power farms or sustainable waste facilities.

Sustainability-linked bonds, on the other hand, can be linked to any project as long as certain sustainability goals are met during the period in question.

Transition bonds meanwhile are like green bonds in that they are linked to a specific project, but the biggest difference is that issuers of transition bonds do not have to already be operating sustainably.

In other words, issuers can be companies (or a government in this case) that are in the process of transitioning to a lower carbon existence.

This means that, theoretically, any company operating in any industry could issue a transition bond.

“Transition bonds have the potential to provide access to the sustainable bond market for issuers in sectors that do not generally qualify for green bonds, but still want to reach climate and other environmental goals,” said a report released by the S&P.

Not for any company

At the moment, major lenders including the Asian Development Bank (ADB) are refusing to fund projects like coal mining or natural gas exploration.

However, the ADB has said that it will give financial support to companies that are transitioning to cleaner solutions, essentially giving their blessing to transitional bonds.

“We think transition bonds can be the next evolution in helping allocate capital towards a low carbon economy,” said a note from BNP Paribas.

But some questions remain; for example, can any company actually issue transitional bonds regardless of the nature of their business?

“We note that some darker brown companies, such as coal mining, will never be able to transition successfully to a greener business, and as such are likely to be excluded from issuing transition bonds,” added BNP.

The biggest challenge of all in establishing a solid transition bond market, according to BNP, is whether issuers are capable of gaining investor trust.

“Part of the challenge faced by the sustainable bond market has been the lack of globally-accepted definitions or verification, and transition bonds potentially face the same issues,” BNP concluded.

Confusion on definitions

While Japan’s issuance could potentially trigger a sea change, it’s worth acknowledging that the transition bond label has struggled to secure widespread adoption.

The reasons for this are manifold, and like BNP said, the biggest problem is that there is no universally accepted definition of what transition finance is.

“There is a multitude of definitions of transition out there, but none has been internationally agreed upon,” said Jarek Olszowka, head of sustainable finance IBD at Nomura.

“This, in turn, has led to a lot of confusion among international investors as to what is meant by a transition bond. The lack of agreement on the definition is preventing market growth.”

Related to this is a fear of being accused of ‘transition washing’ — which is when companies provide so-called green finance to bankroll carbon-intensive firms that do not actually use the money to pivot their business away from fossil fuels.

But there’s no doubt the sector is changing rapidly – Australia and Canada for example are working on their own transition finance definitions.

Urgency in Australia

Australia aspires not only to transition its economy to net zero, but also to become a green energy superpower.

That will involve constructing a host of solar and wind farms, batteries, and electric vehicle charging stations, not to mention upgrades to the grid and investments in new technology.

All this needs funding, lots of it, to the tune of some $755 billion in power generation alone.

The scale means that superannuation funds and other big institutional investors must be involved to support the government’s effort.

The government has issued its first green sovereign bond in June last year, but more needs to be done to fill the funding gap – and that may involve the use of transitional bonds.

“Australia’s financial system must urgently transform itself to meet the climate challenge,” market experts Alison Atherton and Gordon Noble wrote in The Conversation.

“If the financing of the transition were a bicycle race, Australia has now caught up to the global peloton. The next step is to take the lead.”

How ASX investors can get some action

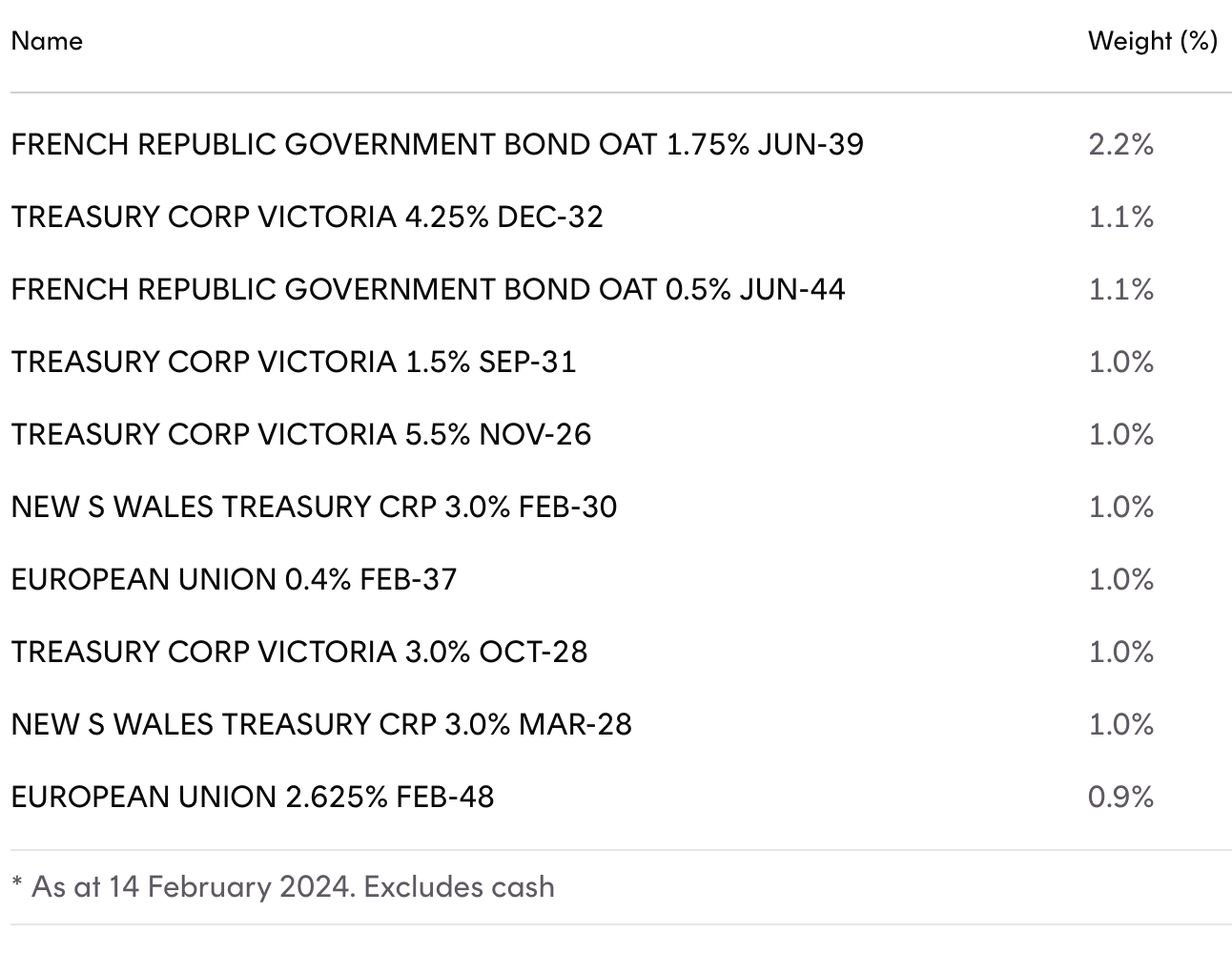

While an ETF focusing on transition bonds isn’t available just yet, ASX investors can still invest in a green-bond themed ETF through the Betashares Sustainability Leaders Diversified Bond ETF – Currency Hedged (ASX:GBND).

Betashares says that at least 50% of GBND’s portfolio is made up of “green bonds” (using the definition applied by the Climate Bonds Initiative), issued specifically to finance environmentally friendly projects.

The fund’s objective, as per the term sheet is:

“To track the performance of an index that comprises a portfolio of global and Australian bonds screened to exclude issuers with material exposure to fossil fuels, or engaged in activities deemed inconsistent with responsible investment considerations (other than sovereign bond issuers).”

The fund’s country allocation includes: Australia (37%), Germany (11%), and the US (3%).

In the past year, the ETF has returned 4.03% after fees of 0.49%.

The composition of the portfolio as of February 14th, is as follows:

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.