The real numbers behind what hydrogen can do – and what it can’t

Pic: Matthias Kulka / The Image Bank via Getty Images

Hydrogen is well on the hype train but two studies suggest that it’s not going to be the green power money maker everyone expects.

A study out of consultancy McKinsey says Japan electricity will need to cost $60 a megawatt hour (MWh) for Australian exports to breakeven.

And a report from Jacobs says it’s cheaper to fuel the Perth-Melbourne train with diesel than with hydrogen.

Hydrogen can be used in fuel cells for long distance transport, exported as ammonia to be converted back into hydrogen in Japan and South Korea for an electricity source, or as a replacement for natural gas as either an industry feedstock, such as to make fertiliser, or a source of heat.

It’s made either by electrolysis from water, a highly energy intensive process that politicians and industry are eyeing renewables for, or from natural gas or coal.

The Japan option

Japan is the main possible export market named by Australian hydrogen fans, alongside South Korea, China and Singapore.

Japan’s government is being particularly aggressive in slashing the emissions of its energy imports, and in March Queensland University of Technology’s (QUT) solar cell facility shipped 3 litres of hydrogen as part of a pilot to Japan.

Mckinsey senior export Godart van Gendt said at the Australian Energy Week yesterday he expects the cost of building electrolysers — the technology that separates the oxygen and hydrogen molecules in water — to come down by 70 per cent over the next decade.

- Subscribe to our daily newsletter

- Join our small cap Facebook group

- Follow us on Facebook or Twitter

But it may not be enough to create the export market people are saying will backstop an industry.

He says it’ll be 2040 by the time Australia has a large enough industry to export sizeable quantities of hydrogen.

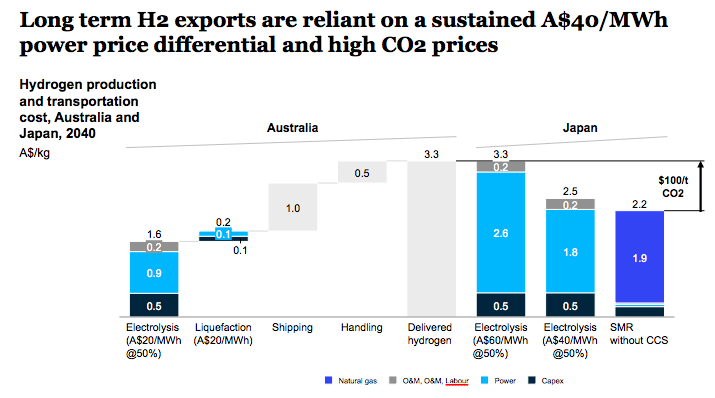

Using an energy price of $20/MWh in Australia, plus shipping, handling and liquefaction, making and getting hydrogen to Japan will cost $3.30/kg — or $25 a gigajoule (GJ). That’s three times the current price of LNG in Australia and Japan.

Japan power prices would need to remain at or above $60/MWh by 2040 to make Aussie hydrogen imports financially viable, or a $100/tonne carbon price.

CSIRO in its report last year said Australia should ship hydrogen as ammonia, but van Gendt says no one knows yet how much it will cost to transport and reconvert hydrogen from ammonia, nor what the losses might be.

It’s also a bet that floating offshore wind and tethered offshore wind technologies don’t work to bring Japan’s power prices down.

The Aussie case

At consultancy Jacobs, Henry Swisher was riding the Perth to Melbourne train, which would need 23 tonnes of hydrogen a day.

“Neither of the hydrogen scenarios were as economically viable as using diesel,” he said during a presentation of his hydrogen white paper yesterday.

“But even though the result was negative… we’re not that far off making it economically viable.”

Diesel prices would need to rise just 18 per cent to around $1.10/litre to make the base hydrogen case feasible.

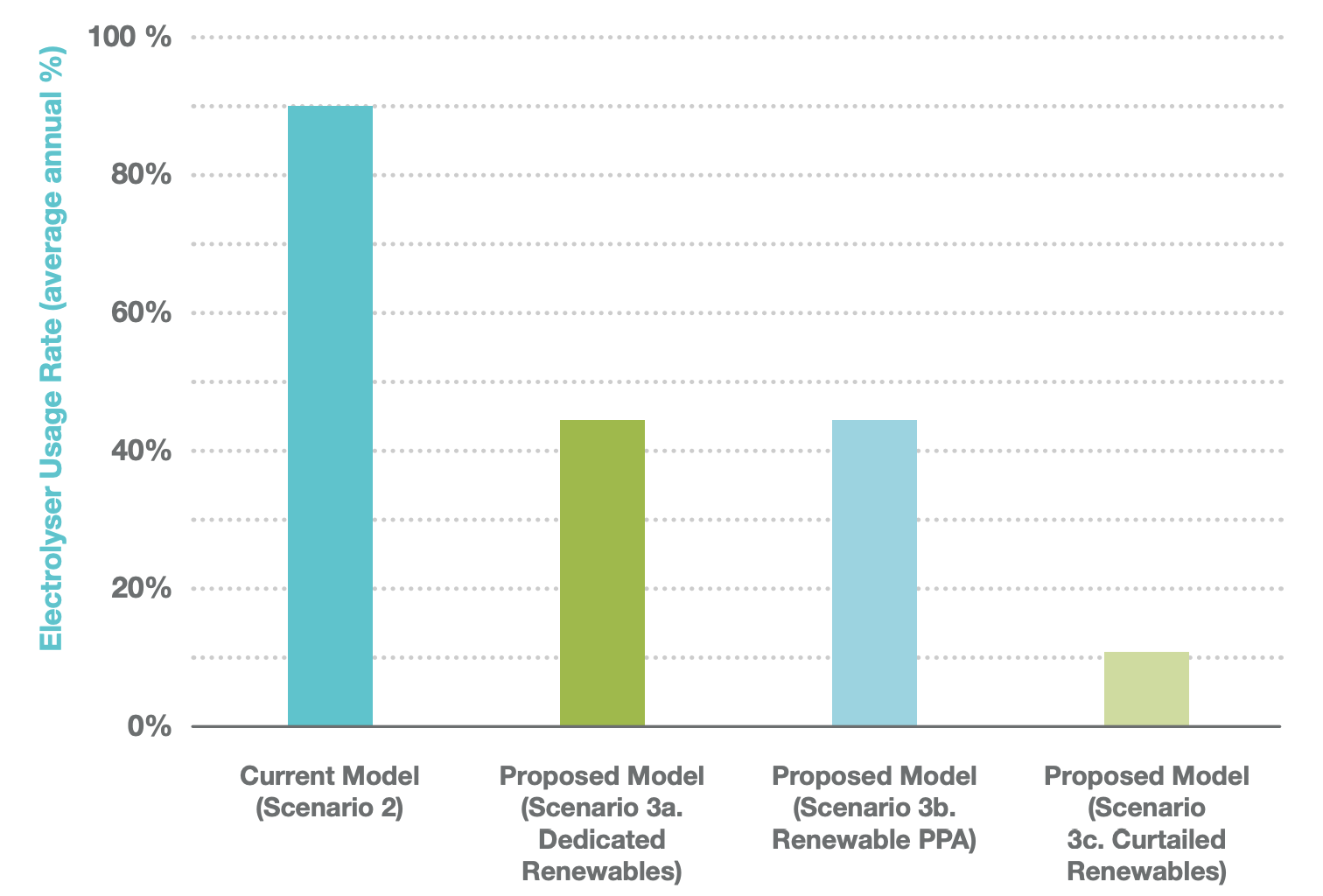

The ‘current model’ is to use drinking water — at times a scarce resource in Australia — and any energy sourced from the grid.

The proposed model looked at building bespoke renewable energy farms for exclusive hydrogen-making use, buying power from the grid and offsetting emissions, and using renewable energy that has been preventing from entering the grid for stability reasons.

Using waste energy might make it more viable but the main takeaway was whether the energy source needs to be ‘green’, now.

“Does hydrogen need to be zero emissions today or can it be low emissions with a trajectory to zero emissions in the future?” Swisher said.

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.