Power Up: We need to have a talk about nuclear energy

Getting serious about why nuclear it isn't viable in Australia. Pic: Getty Images

There is little doubt that nuclear energy powered by good old uranium will play a key role in the ongoing global transition towards net zero emissions.

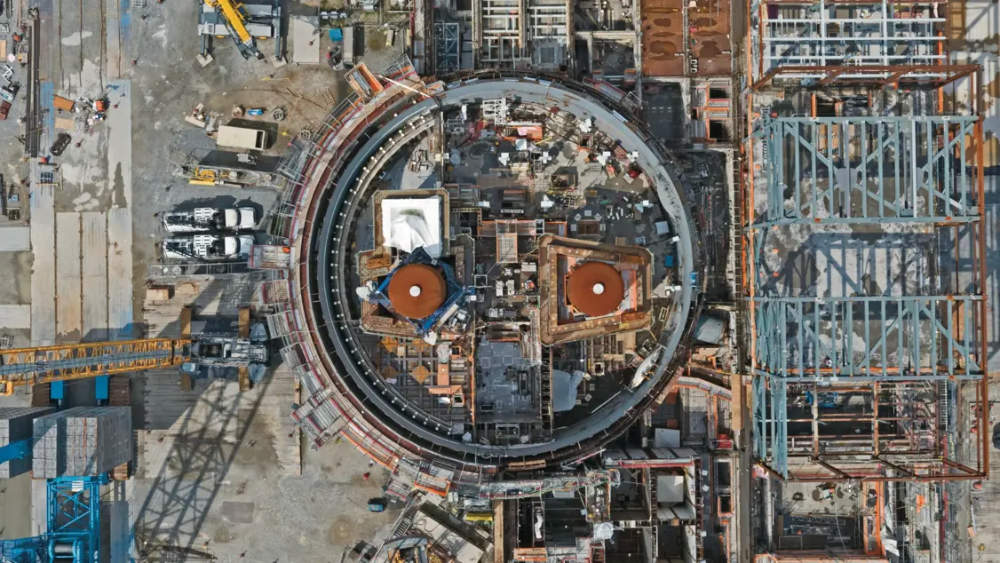

Nuclear power already accounts for about 10% of all electricity generated globally and is likely to make up a bigger percentage in the years to come with the World Nuclear Association flagging in April that ~60 reactors are currently under construction with another 110 planned.

While this is partly offset by old plants being retired, it does provide the world with a significant base of clean, reliable baseload power to back up renewables and take us into the zero emissions future.

Unsurprisingly, this makes nuclear an attractive option for certain ideologies who simply cannot even consider renewables backed by storage as an option.

Coalition hedges its bet on nuclear

The Liberal-National Coalition is one such supporter, naming seven locations that it will pick from to build an initial two nuclear power plants if they are elected to government.

In its media release, opposition leader Peter Dutton claimed that each of the locations – the site of existing coal-fired plants that have closed or are scheduled to close – was selected due to having important technical attributes needed for a nuclear plant.

These include cooling water capacity, existing transmission infrastructure, which eliminates the need for building new poles and wires, and a local community with a skilled workforce.

As for how they will be funded, he said that the Australian government would own the assets but will form partnerships with experienced nuclear companies to build and operate them.

The Coalition is leaving open the decision to use either small modular reactors or modern larger plants such as the AP1000 or APR1400 and flagged that they could start producing electricity by 2035 (with small modular reactors) or 2037 (if modern larger plants are found to be the best option).

Reaction circus

Rather predictably, the announcement sparked off a round of reactions that ranged from bouquets to brickbats.

The Minerals Council of Australia was one of the supporters, saying that the policy provided a critical pathway for Australia’s industries to reduce emissions cost effectively while maintaining access to reliable baseload power.

Support also came from the South Australian Chamber of Mines & Energy, which said that nuclear should be included by decision makers and regulators as a reliable, efficient, small-footprint and net-zero power source.

This enthusiasm might stem from a combination of having presumably cheap power and a domestic market for uranium.

However, these voices were few and far in between, especially when compared to the those opposed.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described the Coalition’s policy as a “fantasy” that was a recipe for higher energy prices, for less energy security and less job creation while Energy Minister Chris Bowen said it was aimed at boosting the life of fossil fuels.

This theme was taken up the various climate groups with the Climate Council saying the opposition’s move was “a smokescreen for its commitment to coal and gas” that would delay the shift towards clean energy.

Meanwhile, the Australian Conservation Foundation said the announcement offered no clarity on technology, cost, timing or waste.

“The Opposition leader has named seven places where he wants nuclear reactors to be built, but he hasn’t been clear about the technology he wants to use, the cost to taxpayers, the timing, or what would happen to the radioactive waste that stays toxic for thousands of years,” the ACF’s nuclear analyst Dave Sweeney said.

Does nuclear have a place in Australia?

So does nuclear energy have a place in Australia’s energy mix?

Much as its advantages would make it welcome, there are many points that mean that it simply won’t be a proper fit.

At the end of May, Power Up highlighted several points why nuclear isn’t feasible in Australia that we will sum up here.

First of course is the CSIRO’s modelling showing that it would cost at least 50% more than solar and wind while contributing nothing to our energy or emissions reduction until 2040.

Second is the overwhelming tendency for mega projects of any type to attract cost overruns.

You can read more about these points here.

The Coalition’s proposal has done nothing to address these concerns. No details were released about costings and within costings, we are not going to know if there has been any provision for cost overruns.

Its plan to own the plants also had Monash University associate professor Roger Dargaville pointing out that it was interesting that the party that “worships the free market is proposing that the new infrastructure be paid for and owned by government.”

He also rubbished Dutton’s claims that the plants would reduce energy costs, saying that nuclear had been clearly shown to be more expensive than renewables plus storage and that choosing to go this route would result in higher energy prices.

There are other factors as well.

While it is all very well that the Coalition has selected sites with “skilled labour forces”, we have to question exactly what it means by a skilled labour force.

As far as we are aware, they are no labour forces with any skill in building nuclear reactors anywhere in Australia. If we are talking about operations, workers used to coal plants will need to be retrained – sometimes extensively – in order to be able to work at nuclear plants.

There’s also the question of capacity.

While Dutton has committed to the first two plants, nothing was said about how many reactors each will have or what kind of total production capacity.

More reactors will mean higher costs and longer lead times to producing electricity.

And if we assume the absolutely bare minimum of one reactor per plant, using Dutton’s example of the AP-1000 reactor, we are looking at just 2.2GW of power.

That is a fraction of the 32GW of renewable power – or half the current National Electricity Market capacity – that the Labor government is looking to add to the grid by 2030.

As for those expecting a domestic market for uranium, on average a 1GW reactor will use about 27t of uranium each year, meaning that the minimum capacity noted above would require 59.4t per annum, hardly a dent to the 4820t of U3O8 that Australia produced in 2022.

We are going to be building submarines aren’t we?

But wait, you say. What about Dutton’s comment that we are already going to build nuclear submarines and how that means Labor has already signed off on its safety and disposal of waste?

It might sound similar, after all they are both nuclear power plants right?

Well, it’s yes and no.

While the principles of nuclear power generation are broadly the same in that they both generate heat that boils water off into steam that in turn drives steam turbines – making nuclear plants essentially high-tech steam engines, they are different in other areas.

Any future nuclear submarine operated by Australia will likely be akin to the Virginia-class attack submarines that we will acquire from the US, which have plants that generate 210MWth to power a 30MW pump jet propulsion system – ie they won’t actually have 210MW of usable power.

That’s at least an order of magnitude (closer to two really) less than the 1.1 gigawatts (GW) pumped out of the much larger AP-1000 reactor quoted by Dutton in his press release. Here’s some reading material on this very topic.

Submarine reactors also use a far more highly enriched type of uranium fuel to generate power compared to their land-based counterparts.

Submarines, being surrounded by water at all times, have no issue with cooling while land-based power plants need a ready supply of cool water, something that can be a fair bit harder to get in Australia despite Dutton’s claims that the selected sites have sufficient cooling water capacity.

There’s also the niggling point about when they will be built. Australia will initially receive second-hand nuclear submarines and will only get around to building its own submarines in the early 2040s.

Needless to say, this is significantly more realistic than the Coalition’s plans that call for the first plants to start producing electricity by 2035 or 2037, which would include the lengthy process of environmental clearance, community engagement, design work and securing long-lead items.

All this is before we consider that most of the arguments against nuclear in Australia is about the cost and timeframes, so we have to question what relevance the comparison actually has.

The conclusion is simple. The Coalition’s nuclear policy, based on what has been released to date, doesn’t add up and can be chalked up to more political hot air.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.