Here’s how Queensland can help solve the East Coast gas crisis

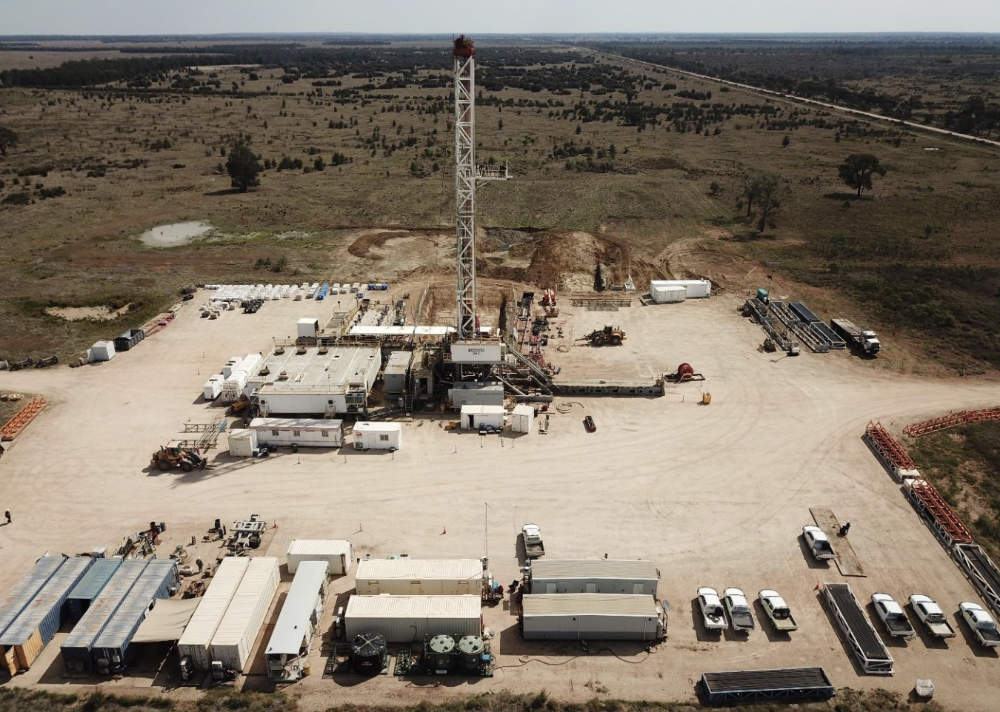

Queensland's gas could be at least part of the answer to solving Australia's forecast gas supply crunch. Pic: Getty Images

- Queensland’s gas basins have both scale and proximity to infrastructure to help meet East Coast demand

- Taroom Trough edges out NT’s Beetaloo Basin with the latter facing the “tyranny of distance”

- Untapped coal seam gas fields can also play a role thanks to their access to pipelines

Queensland might hold the key to addressing the looming gas supply crunch on Australia’s east coast but much needs to be done to overcome the multitude of challenges that will enable this future.

While concerns about supply only really filtered into the collective consciousness earlier this year when the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) blared a strident warning in its 2024 Gas Statement of Opportunities, the truth is it has been flagging its concerns for several years now.

And it is not a lone ranger.

Self-interest aside, the gas industry has also voiced its concerns with major gas producer and electricity generator AGL Energy (ASX:AGL) warning about shortages in a research paper released way back in the mid-2010s.

A key point AGL raised was that while households and small businesses were unlikely to experience any risk to their gas supply, any gas shortages will affect large manufacturing customers.

How we got here

This sorry state of affairs is the result of a combination of factors.

First off is the decline in Bass Strait gas production, which has been a mainstay of gas supply in the east coast for nearly 60 years.

The focus on producing the rich Bass Strait oil bounty meant that gas was either left behind to maintain reservoir pressures or produced as a byproduct, which allowed New South Wales and Victoria to enjoy relatively cheap gas for decades.

Those oil production days are largely over and the fields are mostly in the last phase of production, which involves what the industry terms as “blowing down the gas cap”, essentially deflating the reservoir pressure that had driven liquids recovery.

Notably, this has also led to production declines with the AEMO flagging a nearly 50% drop in output by 2028.

Speaking to Stockhead, Omega Oil & Gas (ASX:OMA) CEO Trevor Brown said the Melbourne and Sydney markets have taken the Bass Strait for granted.

Meanwhile, global warming has led to all fossil fuels being thrown into one basket.

“Coal, gas and oil have been demonised in the eyes of the general public and the politicians have reacted to that by advocating strongly for renewables and subsidising renewables, and providing all kinds of market incentives to disincentivise the use of natural gas along with coal,” Brown noted.

“Market based mechanisms giving preferential entry into the market for renewable production and direct subsidies of renewables have undermined the economic case for the development of new sources of gas.”

This has been exacerbated by direct disincentives such as gas caps and interventions.

Comet Ridge (ASX:COI) managing director Tor McCaul concurred, saying the $12 per gigajoule gas cap had made bigger companies wary of investment in Australia.

Ironically, the cap is now the unofficial floor price as it was essentially the Federal Government declaring that $12/GJ is a fair price for gas.

“It really did slow investment and now there’s a worry (about) what other interventions they could come up with over the next few years and how do we keep Victoria and New South Wales supplied,” McCaul noted.

Along with factors such as the big drop in oil prices in 2014, the oil and gas sector has seen a large reduction in exploration and appraisal spending across Australia and the world.

“We are down to about 10-20% of the previous level, and that’s about a decade of neglect in exploring for new sources of gas,” OMA’s Brown noted.

“The fundamental issue in the short term is that we haven’t invested enough in exploration and appraisal. That means there are no big gas fields in the pipeline that can be developed in the timeframe and scale that we need.”

LNG imports filling gap?

This raises the possibility that Australia’s east coast might be forced to lean on LNG imports to meet its needs.

“If you look at the AEMO Gas Statement of Opportunities, there is a big gap emerging as early as next year and we cannot possibly supply the volumes that are required,” Brown said.

“It is going to lead to shortages during peak usage times in the south where you get weeks of cold weather and don’t get much input from renewables, meaning you need a lot of heating on top of all the industrial base usage.

“That’s when the crunch will come and the southern markets will be undersupplied.

“They are drawing as strongly as they can on the supplies from the Bowen Basin, and they are storing what they can in the available storage in the southern markets, but those storage facilities are relatively small and cannot sustain more than a few days of peak demand.

“Then they will have to resort to what is euphemistically known as demand management, which means shutting down large-scale industrial users and I don’t think many of them will tolerate that for very long.

“So the only short term solution is importing LNG for the East Coast.”

Andrew Forrest’s Squadron Energy is betting on this with its Port Kembla import terminal near Wollongong nearing completion.

Imported LNG is not cheap, with McCaul suggesting buyers would balk at prices that could hit as high as $20-21/GJ. Squadron could seek government guarantees through a take-or-pay agreement.

“The only problem with imported LNG is the pricing and I don’t see it as a threat to any of us. I think if anything it will actually lift the east coast gas price because it is pitched above what’s currently in the market,” he said.

Brown says importing gas at parity pricing to the international market is not sustainable.

“We need new, indigenous sources of gas on the East Coast.”

New basins to the rescue

While there are existing smaller, peripheral fields in the Gippsland and Otway basins that are commercially attractive due to their proximity to the major demand centres, they don’t have the scale to satisfy long-term.

Brown believes there are only two basins with the potential scale, flow rates and ability to supply the market in a reasonable timeframe.

These are the much touted Beetaloo Sub-Basin in the Northern Territory and the Taroom Trough on the southern edge of the Bowen Basin – a well-established petroleum province.

While the Beetaloo is further along the appraisal curve, it has a big commercial disadvantage due its distance to market.

“It is a big capital cost that will always be built in,” Brown said.

“Secondly, it is a new producing basin and has not had any existing infrastructure or supply chains and it is a long way from anywhere.

“So operators will have the cost of getting rigs, crews, fracking materials and equipment, all of the necessary infrastructure to do a continuous drilling program, they have got wet seasons to contend with and they have all of the environmental issues that need to be sorted through.”

McCaul says while the new Country Liberal NT Government is supportive of the industry, it could cost $5-6/GJ to transport gas east.

In Brown’s mind, its natural market will be north through the LNG plant in Darwin.

The emergence of the Taroom Trough

It is why Brown believes the Taroom Trough has the edge.

Located close to infrastructure and in a mature energy producing basin, it boasts access to services and expertise built around the coal seam gas sector.

“You have rigs, fracking equipment and expertise as well as short supply chains for getting the materials,” he noted.

“It is an existing producing province with landowners, local government areas, etc that are comfortable and welcoming of oil and gas developments.

“Existing baseline environmental studies, understanding all the aquifers, monitoring all the environmental requirements, are all in place, operating and well documented.

“It is a very big head start.”

Now Taroom Trough operators such OMA need flow rates out of wells that prove its long-term commerciality.

While Elixir Energy (ASX:EXR) achieved lower than previously measured stabilised gas flow rates from its Daydream-2 vertical well, Brown noted they appeared to have experienced a few issues while the company itself has claimed that the flow rates could be remedied in future.

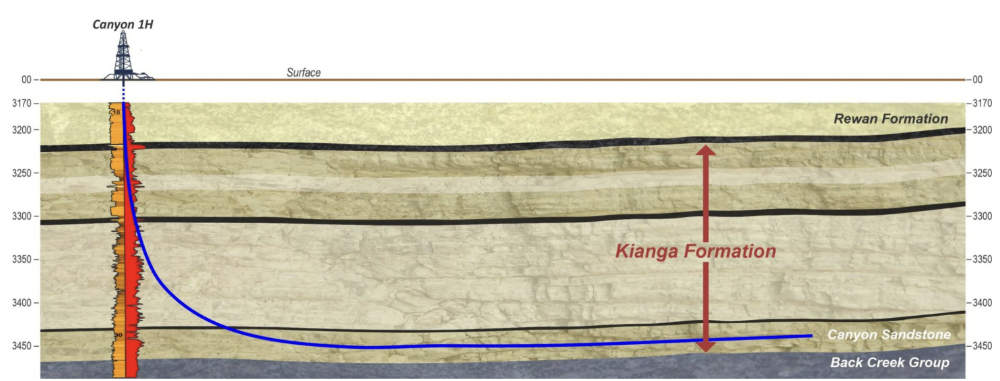

More pertinent to OMA’s plans, which currently involve drilling the Canyon-1H horizontal well, is Shell reportedly achieving good results from a horizontal well.

“We are greatly encouraged by the fact that we are seeing things in the same way as Shell, who have an international portfolio and will only allocate capital to projects with both technical and commercial appeal,” Brown said.

The Taroom Trough has two other key features: CO2 content in the region of 1-2%, which is basically pipeline quality, and significant amounts of liquids (condensates) that will improve economics.

“It is one of the things that we have to find out in our appraisal program, what that ratio (of condensates to gas) is and that will help us size the facilities,” Brown noted.

“Condensate production is very valuable.”

Many of the technologies used in the Taroom Trough – like horizontal drilling and fracture stimulation (fracking) – have been used over the last 20 years by the US to turn itself from an energy importer to an energy exporter.

They are now commonly applied and well understood.

This is demonstrated by CSG developers drilling 4km lateral sections in 4m thick coal seams.

“The only difference is that we have deeper reservoirs and higher pressures but it’s the same technology,” Brown said.

He added that the 300m interval intersected by the company had several different layers within it, some of which will be more attractive than others.

“We are only appraising one layer within our first well and it will be ideal to have a big success, but if we don’t there are still other potential layers and it will be a long-term appraisal of this basin,” he said.

“I suspect we will find a way to understand how we can get commercial production of this well.

“It is just too attractive and well placed. It has all the underpinnings of scale and timing we need.”

Queensland’s Good to Go

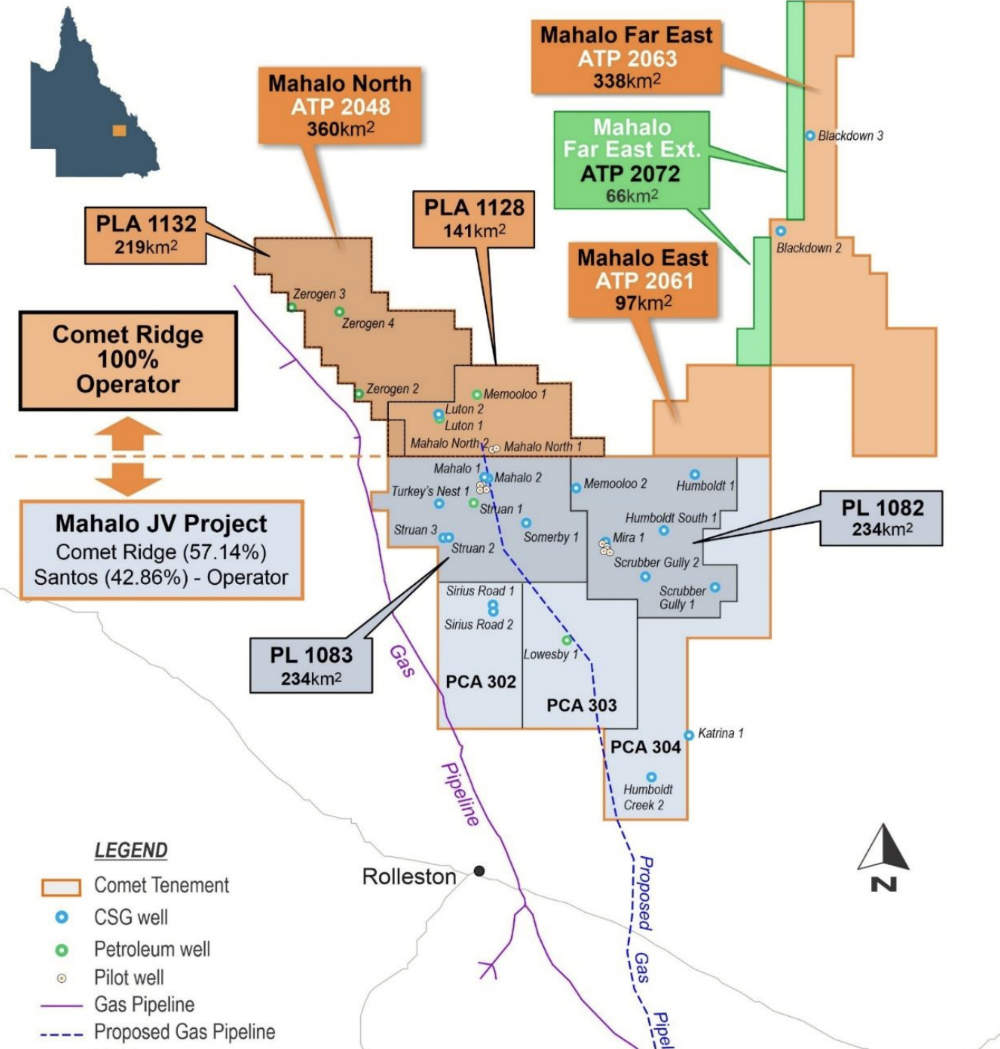

Outside the Taroom Trough, McCaul believes COI and its much shallower 250m deep coals near existing infrastructure at its Mahalo Gas Hub in the Bowen Basin can answer the call.

“We have contingent resources on the east side and so have started drilling the vertical Mahalo East-1 vertical well, which is the evaluation well that we will get all the log and core data from,” he said.

“Then we will move the rig about 370m (and) start the lateral (Mahalo East-2) and turn the corner on the lateral to intersect the vertical and go out the other side and keep drilling coal while we can.

“It looks a little bit like the Mahalo North wells we drilled a couple of years ago. If you drill a vertical well, you get about 8m of coal.

“But if you drill a horizontal or lateral well, you can get lots of coal, it just economically makes sense to drill them.

“Santos to the south of us have drilled 4000m of coal out there.”

While COI is currently focused on getting Mahalo up and running, McCaul believes the larger, more frontier Galilee Basin in central Queensland will have its day in the sun.

“I’m always a bit surprised the Galilee hasn’t garnered more attention, I think it is because only the little guys focused up there,” he said.

“It still has distance to infrastructure as a concern, but it is in central Queensland, so it is much closer to the market (compared to the Beetaloo).”

Remaining challenges

While Queensland appears to have the resources needed to meet East Coast gas demand, pipeline capacity remains a critical issue that needs to be solved.

While APA has already expanded pipelines from the north by 25% to 512 terajoules per day (TJ/d), a planned Phase 3 expansion to add another 128TJ/d is currently pending resolution of some issues with the Australian Energy Regulator on tariffs.

EnergyQuest’s September Quarterly said even this addition would not be enough to solve the capacity issue during peak times. More storage is needed in the southern states.

McCaul agreed, adding that because of pipeline capacity, there is only a finite amount that the Sunshine State could do to help the southern states.

“They have to help themselves beyond that.”

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Comet Ridge and Omega Oil & Gas are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.