Helium is exploding onto the scene again. Here’s why Shortage 4.0 is different

It's high time we sorted out this helium supply shortage. Thankfully, there are ASX gas plays that are doing just that.

Helium has a chequered history. It’s lifted us up, made us laugh – and made us cry – yet crucially it’s intrinsic to our technological advancements.

Supply is tight at the moment. They’re calling it ‘Helium shortage 4.0’ – the fourth time since 2006 that the world has experienced supply shortages that have been largely due to external geopolitical forces, production faults, or planned maintenance shutdowns from major producers such as Russia, the US and Qatar.

These shortages have caused project delays for researchers and sectors who are reliant on the element as noted recently by scholars at Harvard University.

The culprits are varied. A ramp-up in production from Gazprom’s Amur plant in Eastern Siberia was stalled by two gas plant fires in late 2021 and early 2022, sending supply shockwaves across a range of sectors.

Other impacts last year were the shutdown of the US Bureau of Land Management’s crude helium production unit from January to June and Algeria was forced to shut down its Arzew plant to supply natural gas to Europe – a geopolitical consequence of the war in Ukraine.

Helium supply was already constrained before this whole shemozzle, because in 2017 Qatar had to shut down two of its helium plants due to an economic blockade imposed by Saudia Arabia. And get this: Qatar is also closing down its Ras Laffan facility for maintenance this year. Bonkers.

Because of this circus, the helium market is reported to register a conservative compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of greater than 4% across the period between 2017 and 2027 as these major producers eventually get their mojo back.

This is good news for startups in the helium biz, but it’s not new news either:

#Helium markets are now experiencing ‘Helium Shortage 4.0’ – but unlike previous sustained helium shortages, increased exploration for and production of helium is seen as the only solution this time.#HEV pic.twitter.com/H7kBjZtjVZ

— HeliumVentures (@HeliumVentures) May 10, 2022

Analysts forecast the global helium market size will grow from US$4.45 billion last year to US$6.48 billion by 2027 – but Kornbluth Helium Consulting founder and president Phil Kornbluth says it’s likely currently closer to a US$6-7 billion a year market right now because of the opaqueness of major producers not sharing material information at the macro level.

“I don’t believe prices will go up as much in 2023 (as they did in 2022), but when Amur begins to sustain material production, prices would be expected to moderate,” Kornbluth said.

“There’s quite a lot of uncertainty between now and 2027, a lot of activity aimed at developing new sources and it’s a great time for a start-up to be producing helium and earn a nice return, if they can get into production.”

When it comes to how quickly prices come down and by how much, he points to the fact that in the past when shortages are followed by oversupply, the industry typically held on to about half of the price increase they got on the way up.

Companies such as Blue Star Helium (ASX:BNL) are on a voyage to become one of the first ASX-listed pure-play helium producers, with advanced wells in Colorado.

There’s also Grand Gulf Energy (ASX:GGE) plugging away at its Red Helium project in Utah, while Noble Helium (ASX:NHE) is over in Africa planning its first drilling campaign at North Rukwa, Tanzania, this quarter.

We’ll get to them. But first, let’s raise some facts

The only element in the periodical table that physically leaves the planet, helium is paradoxically also used in our technological ability to travel into space.

That also means helium is finite – mined from trapped pockets deep under the surface through the chemical decay of radioactive bullies such as uranium and thorium.

And if you happen to remember your ’80s cartoons, Alvin and the Chipmunks once popularised helium to the point where rubber balloon costs had inflated to astronomical levels.

This time around, much of the demand has to do with helium’s ability to liquefy at just 4.2 degrees Kelvin (−452.1F), which is a huge benefit to scientific and laboratory processes that require super cold temperatures.

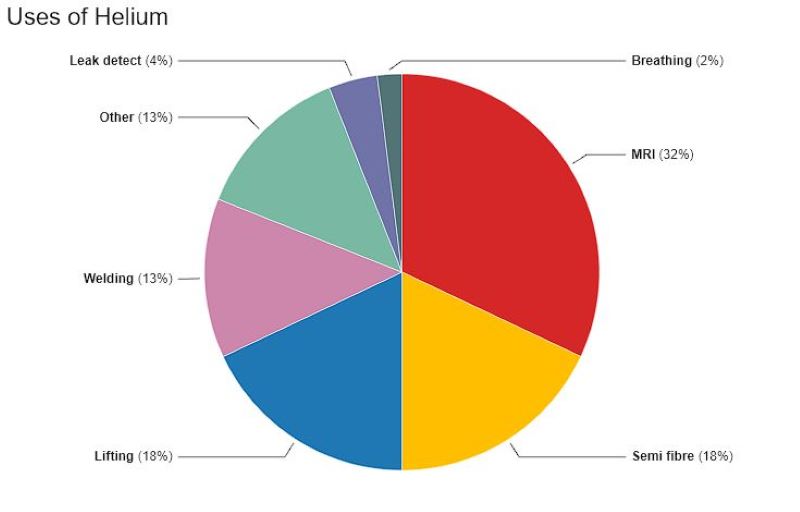

So, apart from the party balloon racket and The Chipmunks’ propensity to popularise their demand by sucking the life out of the party, helium also has historic and insanely relevant uses in nuclear energy production, solar panels, optic fibre and the cooling of superconducting magnets in MRI scanning machines and more – all vital tools for their respective sectors.

Laugh all you want, but helium is again scarce, and analysts for a while have seen that supply constraints are only pushing prices higher.

Let’s look at how it all began.

History

At the same time WWI was making its presence known, US scientists were discovering huge helium deposits in Kansas, then weaponising the element to float balloons packed with bombs in ‘dirigibles’ that caused carnage and often crashed soon after.

The US was adamant that helium would be vital to end the Great War, so it nationalised, extracted and stockpiled it for the war effort, only for the war itself to end before it could be utilised.

“If the war had lasted until next spring, the British and American Governments would have sent helium-filled rigid airships over strategic points in Germany, each capable of dropping a ‘total of 10 tonnes or more of high explosives.” – Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The Yanks had the supply chain in place, so they continued to control the world’s helium, searching for its uses but not finding much to do with it – which was pretty unfortunate for those aboard the hydrogen-filled Zeppelins the Germans built.

In early 20th-century balloon circles, hydrogen ended up being a teeny-tiny bit too combustible; as was found out when the British used incendiary bullets to shoot down the war-mongering Zeppelins.

Unfortunately for many, commercial operations across Europe kept using hydrogen-filled passenger aircraft to float from destination to destination, until…

“Oh, it’s crashing . . . oh, four or five hundred feet into the sky, and it’s a terrific crash, ladies and gentlemen. There’s smoke, and there’s flames, now, and the frame is crashing to the ground, not quite to the mooring mast. Oh, the humanity, and all the passengers screaming around here!” – Herb Morrison, Hindenburg disaster reporter, 1937.

Hydrogen-filled balloons had sung their swan song that year, but rather than disappearing into thin air like our guy helium does all the time, hydrogen’s destructive streak reared its ugly head once again in the Marshall Islands in 1952, exploding 500 times more powerfully than the atom bomb dropped on Nagasaki in WW2.

The celebrated aspects of hydrogen were tarnished.

With the US still holding its noble helium cache and trying to find ways to make it productive in the post-war era, it allowed the element to grow into the key ingredient it is today for a plethora of vital industrial and technological uses.

Who on the ASX is into helium?

Back onto the ASX and Grand Gulf Energy (ASX:GGE) has just assessed its McCracken prospect and generated a gross P50 helium resource of 1.8 billion cubic feet (BCF) (1.3 BCF net to incorporated JV company – Valence Resources), which complements the developments of its Jesse-1A, Jesse-2 and Jesse-3 wells in the Four Corners Area of its Red Helium project, Utah.

This brings the P50 total for Red Helium to 12.7 BCF.

“The Devonian McCracken sandstone is a proven producing helium formation in the region, and the P50 prospective resource booking of almost 2 BCF at a gross level and 5 BCF at a field level represents a highly prospective bonus formation with significant upside that Grand Gulf will target at the Red Helium project,” GGE MD Dane Lance said.

Then there’s Noble Helium (ASX:NHE) progressing its North Rukwa project, remaining on track to drill its first wells in Q3 2023.

The two wells will target structures with a combined mean Prospective Helium Resource of

16.5Bcf within the East African Rift System. Both wells are Basin Margin Fault Closure (BMFC) plays.

To date, BMFC plays have a proven 100% discovery rate from 14/14 oil and gas exploration wells in other basins of the East African Rift System in Uganda and Kenya.

Yet perhaps the nearest towards production is Blue Star Helium (ASX:BNL) which is fast-tracking the commercialisation of its Colorado helium asset Voyager and the bigger but less developed Galactica/Pegasus wells.

The company is eyeing first production sometime towards the end of this year and has will have access to a helium recovery unit (HRU).

It recently shook hands with US-based midstream gas provider IACX Energy at the end for the latter to provide helium recovery services, via the delivery and operation of an initial HRU at Voyager – with Blue Star to provide secure access to the facility and deliver the raw gas to the inlet in exchange for a monthly stipend.

Nameplate raw gas throughput is aimed at 2 MMcf/dau to produce a 98+% purity helium product gas. Nice numbers.

Targeted helium production based on an average of 8% helium in the raw gas is expected to be ~38 MMcf net to Blue Star in its first full-capacity year.

Forecast total field and plant operating costs also look highly attractive, coming in at ~US$100-120/Mcf of helium product gas (at full capacity).

“As well as delivering significant de-risking benefits in terms of upfront capital, time and operating profile, adopting this pathway has also eliminated any requirement for Blue Star to commit to price concession offtake agreements,” BNL MD and CEO Trent Spry says.

“Now we can target the premium pricing available in short-term US contract markets and spot sales, with current pricing estimates understood to be running at US$450–$3,000/Mcf for 98 to 99.999% purity helium.

“The plant to be supplied at Voyager can be readily expanded via the addition of a modular membrane unit or addition of a second PSA plant to increase helium output in the future, as well as to accommodate additional high He-concentration raw gas from surrounding discoveries.”

Up, up and away!

Voyager’s facility is planned to start up on site-generated power before eventually transitioning to grid power.

BNL has permitted two wells there for drilling and is currently seeking additional permits for a further four initial phase wells.

Production well drilling at Voyager is set to commence during August, with pressure and flow testing to be undertaken post-drilling.

IACX expects to install and commission the facility during Q4 CY2023, subject to receipt of all necessary permits, surface use and access agreements.

Blue Star’s planned Galactica/Pegasus development is a larger-scale and longer-dated project compared to Blue Star’s maiden Voyager project, with multiple potential product streams.

Well flow rate, production and ultimate recovery profiles have been completed for the project, and the near-term start up of Voyager will put the company in a pretty decent position to fund well development.

Further engineering and market work is underway to refine the initial and expanded planned development configuration and forecast helium and potential CO2 production and cost estimates.

The company has a range of development pathways under consideration for its Galactica/Pegasus plays; including an initial leased plant and third-party operated option, with a final development decision expected to potentially include a CO2 by-product stream.

At Stockhead we tell it like it is. While Blue Star Helium is a Stockhead advertiser, they did not sponsor this article.

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.