BCG: The impact of COVID-19 means global fossil fuel demand may have peaked in 2019

(Getty Images)

One of the defining early features of the COVID-19 pandemic was a plummet in demand for oil.

And if global economic growth doesn’t return to pre-crisis levels until 2022, then 2019 may turn out to have represented the peak in the global consumption of fossil fuels, Boston Consulting Group (BCG) says.

Analysis from the firm’s Europe-based energy analysts says if growth is slower to rebound, the pace of industry consolidation around renewable energy technologies could result in a permanent shift.

“The growth in fossil fuels was always going to come to an end, but the COVID-19 crisis may have accelerated this by more than a decade: peak fossil fuel demand may have happened in 2019,” BCG said.

To reach their conclusion the group modelled the demand outlook for coal, oil, and natural gas, based on three separate growth scenarios for the global economy set out by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in April.

Should global growth bounce back — a prospect now looking increasingly unlikely, BCG calculated that fossil fuel demand could be expected to return to pre-crisis levels by 2022.

But here’s their prognosis in the event the recovery lags and takes on the so-called “U-shape”:

“With insufficient economic growth to offset other forces, demand for fossil fuels will not move back to 2019 levels until the second half of the decade. And if the energy transition accelerates, this may never occur,” BCG said.

In that scenario, the analysts noted that not all fossil fuels would be equally as hard hit. As a form of fuel that was already getting phased out before the crisis, coal would be first in the firing line.

Oil demand would also fall amid the broader decline in transport and travel, with the pace of that decline to be more heavily influenced by the economic recovery in China and India.

“Demand for gas, on the other hand, would probably nearly resume its previous growth trajectory,” BCG said.

However, energy companies should be mindful of repositioning their medium-term strategies amid what looks like an accelerated structural shift taking place as a result of the crisis.

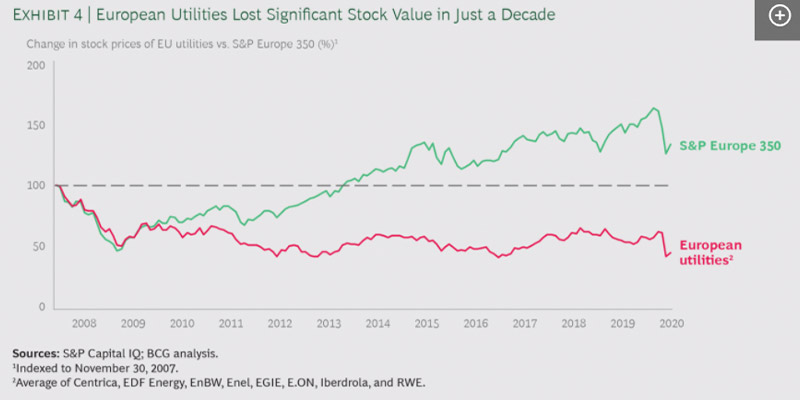

As an example of the negative consequences of inaction, the analysts cited the market performance of European utilities, compared to the S&P Europe350 index since 2009.

“Coal still burns in many European countries today and will likely continue to do so for at least another decade. But once financial markets realised the structural changes that were underway, utilities lost a significant share of their market value within just a few years,” the analysts said.

“By the time utilities accepted that they needed to transform their business models, their ability to fund such a transformation had severely diminished.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.