ACCUs: What are they and why are they in desperate need of reform?

Pic: Vertigo3d / E+ via Getty Images

A series of events over the last few weeks have cast doubt over Australia’s carbon market, putting into question the integrity of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) and the projects that generate them.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s hash-out the nitty gritty.

What are ACCUS and how are they created?

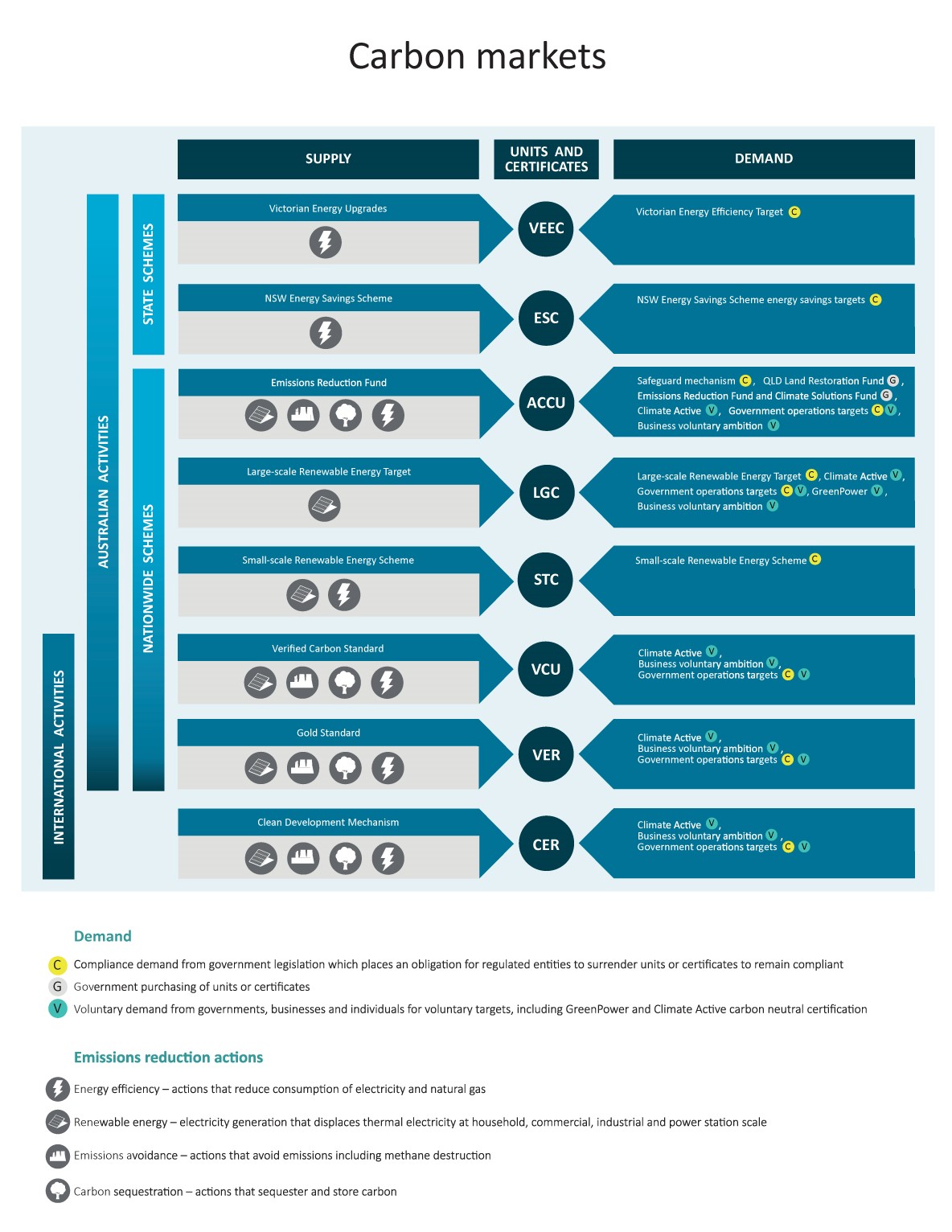

ACCUs are generated by landholders and businesses who carry out various activities across the economy that reduce, store, or avoid emissions.

In exchange for carrying out these carbon abatement activities and in exchange for every tonne of CO2 or CO2 equivalent that is stored or reduced, landholders and businesses are issued with a carbon credit.

These credits can either be sold back to the government through a contract (currently the government is the biggest buyer of ACCUs) or into the secondary, voluntary market with surging demand from big companies looking to offset their own emissions.

As well as having to be ‘real’ and resulting in actual abatement, these credits must also be additional, meaning incentivising abatement that would not have happened unless the project was implemented.

Who administers ACCUs and what is the ERF?

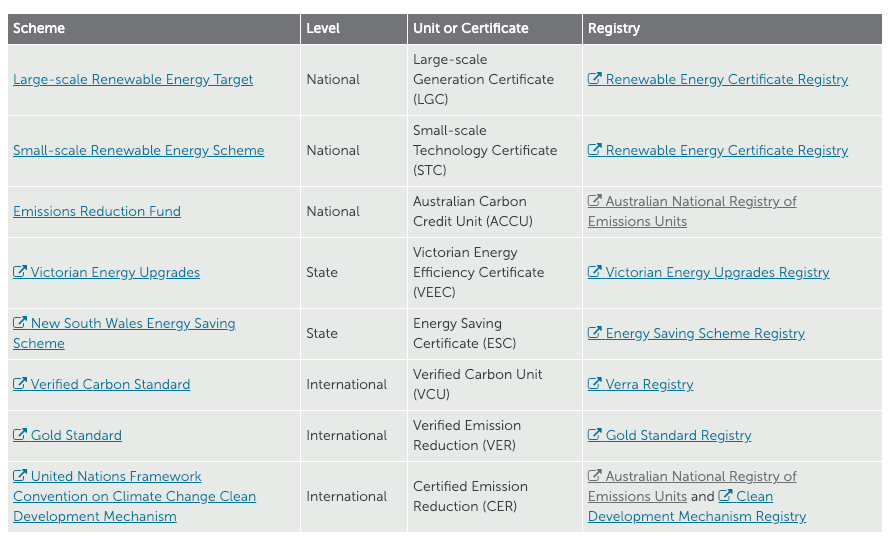

ACCUs are issued by the Clean Energy Regulator – an independent statutory authority responsible for administering legislation to reduce carbon emissions and increase the use of clean energy – under the Emission Reduction Fund (ERF).

The ERF is a voluntary scheme with three key components – crediting emissions reductions, enabling the purchase of emissions reductions, and the ‘safeguard mechanism’ which ensures emissions reductions purchased through the ERF are not displaced by increases in emissions elsewhere.

This safeguard mechanism is important because it is meant to control emissions in certain areas of the economy by placing baselines on the amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) big businesses and industrial facilities emit.

If companies emit more GHGs than they are allowed to, they must buy ACCUs to offset excess emissions.

About 215 companies fall under the safeguard mechanism in industries ranging from mining, oil and gas production, electricity, and manufacturing.

Instead of setting a baseline based on historical emissions as a point of reference with businesses having to keep emissions under that threshold, these baselines are negotiated and are based on emission intensity and forecast production.

Role of the ERF under fire

In principle, the ERF has an important role to play in climate policy given it’s the only legislated climate policy under the Morrison Government.

Both major parties are claiming offset carbon credits represent a key pillar in their pathway to net zero, and it is central to meeting the goals agreed to at the COP26 UN climate summit in Glasgow last year.

At a project level and at a system level, the way the ERF is used should see emissions reductions across our economy.

But for fans of The Office out there, one can draw the analogy to the ‘Schrute Buck’ – the basic unit of currency used for motivation at Dunder Miffin Scranton created by Dwight Schrute.

Dwight incentivises not by paying people directly but by giving them Schrute Bucks, which can be exchanged for things like an extra five-minute lunch break.

Essentially that is what the ERF is, an incentive scheme tokenising buying back abatement.

Most of the ACCUs issued are ‘low integrity’

Last month Professor Andrew Macintosh, the former head of the Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee – whose primary purpose revolves around vetting the integrity of carbon offset schemes under the ERF – labelled the Australian carbon credit system a ‘fraud’, stating most of the credits represent no real or new cuts in greenhouse gas emissions.

This is pretty significant considering Australia has relied on carbon credits to reduce its emissions since 2005.

In four academic papers, Macintosh outlined major implications for the credibility of the ERF, calling essentially for the ‘breaking up’ of the Clean Energy Regulator as well as an independent investigation.

There are roughly about 38 different methods in the ERF, however between 70-80% of the carbon credits issued to offset Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions come from a select three.

These three methods include human induced regeneration, avoided deforestations which rewards landholders for not clearing trees, and landfill gas which pays businesses operating waste dumps for curbing emissions.

In his research, Macintosh claims the issuance of ACCUS under these methods are ‘low integrity’, meaning these projects have effectively done nothing to reduce emissions – in fact, more emissions are getting released into the atmosphere because the credits aren’t real or additional.

Who’s to blame?

Polly Hemming, climate and energy advisor at The Australia Institute, says these issues have been raised for several years and have never been thoroughly investigated.

“Responsibility lies solely with the government and the clean energy regulator,” she says.

“There was an opportunity to carry out a full independent review but the government more broadly, has been negligent here.

“We have no policy or effective regulations to reduce emissions in Australia because the gas industry runs the country.

“If we had adequate climate policy and the government wasn’t actively trying to increase the available supply of offsets to the gas industry then we wouldn’t be faced with a lot of these integrity issues.”

Daryl Killin is a director at The Carbon Hub and a savannah burning specialist with more than 25 years’ experience in all aspects of tropical forestry operations and fire management.

He says the Australian climate change policy framework is not sufficiently advanced to develop economy wide action and that is on purpose.

“The LNP is obviously captured by the fossil fuel sector – I can remember going to Sydney in 1999, we were going to be the first carbon trading scheme in the world – but that got cancelled because of a small delegation of fossil fuel executives who went to see John Howard six weeks from hitting the button.

“That was 23 years ago, we have had over two decades of the fossil fuel sector dominating climate policy and that has got to change.”

Offsets are being used as a licence to pollute

Hemming says integrity needs to be restored in the system but beyond that, parameters need to be put in place around how carbon credits can be used.

“They are only ever meant to be used in generally hard to abate sectors, and only meant to be used as a tool for last resort,” she says.

“The price should be prohibitive enough that it encourages businesses to make reductions instead of being able to buy cheap carbon credits.”

Until we have policies that address the phase out of fossil fuels, as well as a review of the ERF that aims to ensure:

- a) every carbon credit method or project was resulting in actual emissions reductions and avoidance; and

- b) there were limits on which industries could rely on offsets (and how heavily) in their net zero plans

Then we might see some actual climate outcomes.

“Currently, offsets are being used in Australia as a licence to pollute more often than not,” Hemming says.

“When it was just the government buying carbon credits, arguably nothing was happening in terms of abatement, and a lot of public money was being wasted.

“But when those carbon credits are used by big emitters to ‘offset’ greenhouses gases and the credits have no integrity, then nothing is being offset and in fact emissions are increasing.”

The Australian Carbon Exchange

As it stands, the CER is still in the process of setting up a web-based carbon exchange which would remove barriers to entry to the carbon market as business demand for emissions reductions increases.

Brad Kerin, general manager, and company secretary at the Carbon Market Institute, says there are two steps to setting up the exchange. The first is undertaking a GAP analysis to understand what it needs do and what it needs to function and the second involves engaging someone to go out and build it.

The CER has stated on its website proposals will be evaluated in the first quarter of 2022 with the platform to then be launched in 2023.

“We don’t really know what the carbon exchange will look like, but we do know it will show what the credits are, how many credits are available, the price, and possibly other attributes like what type of project it comes from,” Kerrin said.

Killin reckons an exchange is exactly what Australia needs.

“We need to democratise the market, we need it to be more rigorous, more transparent and with a higher degree of integrity so that consumers can understand it and participate directly,” he says.

“Only people with an Australian financial services licence can trade in carbon – the carbon market is opaque and secretive, with about seven different traders who dominate.

“When they buy and sell ACCUs they don’t have to disclose what they buy and sell and there’s no central register where you can see the price of carbon – it’s all over the counter trade.

“We need a transparent carbon exchange – the regulator has proposed that, but my concern is in the meantime, the policy has been made to benefit those over-the-counter carbon traders disproportionately to the rest of the value chain.”

Last thoughts

But for others, like Hemming, the fact that these three methods have been left unchecked for so long asks the question – what else has gone wrong?

“Just because Macintosh has shown these three methods have no integrity, that doesn’t automatically mean that the leftovers do,” she said.

“It has undermined the confidence in the whole scheme and all the exchange does is one thing – cuts out the need for consultants and brokers, so probably makes it cheaper because it cuts out that service fee, but it’s not fixing the fundamental problem.

“It is still allowing the buying and selling of credits that may not have integrity and still allowing big emitters who aren’t reducing their emissions in the first place to have easy access to them.”

Related Topics

UNLOCK INSIGHTS

Discover the untold stories of emerging ASX stocks.

Daily news and expert analysis, it's free to subscribe.

By proceeding, you confirm you understand that we handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.