For investors, this is why ‘prospect generators’ are more likely to deliver the big returns

Mining

Mining

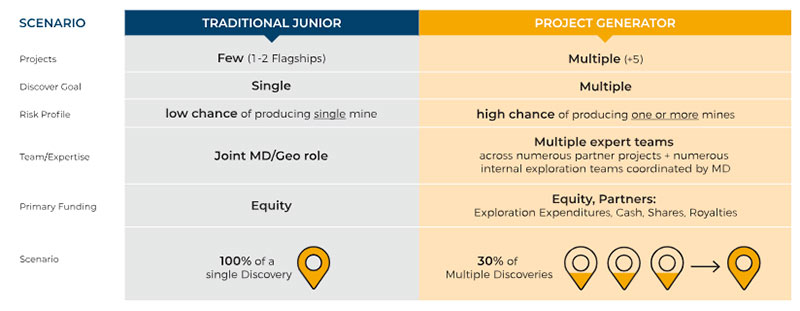

Renowned resources investor Rick Rule has passionately advocated for something called the ‘prospect generator’ model of exploration for years.

Prospect generators are mineral explorers that focus on finding numerous, very promising early stage prospects using very technical methods.

They do the initial inexpensive exploration work to prove up a project’s potential.

Then they attract a cashed-up joint venture partner to fund much of the expensive later stage exploration and development costs.

With a joint partner shouldering much of the exploration costs, a prospect generator can have numerous exciting projects on the go at the same time.

It’s a very rational business model that minimises risk for junior explorers – but for some reason it’s not a hugely popular concept in Australia.

There aren’t a whole lot of listed ASX companies that call themselves prospect generators, but Encounter Resources (ASX:ENR) and Predictive Discovery (ASX:PDI) are two that spring to mind.

Predictive is focused on acquiring ground in West Africa prospective for gold.

It has a pipeline of continuous and early stage exploration plays, and has partnered with experienced, cashed-up companies to fund ongoing exploration.

Predictive managing director Paul Roberts says the whole idea of the prospect generator model is to get many chances at the title.

“Normally a junior explorer can’t sustain more than one or two core projects,” he told Stockhead.

“They may have other projects, but basically, they have to be very highly focussed on one project.

“That’s great, and it makes for a simple, easy to understand story.

“The problem is that most projects don’t become mines.”

Prospect generators won’t ever own 100 per cent of a project, but they benefit from the increased likelihood that one will turn into a mine.

These companies run a tight ship – exploration is lean, technical, and highly efficient which means capital requirements are relatively low.

For shareholders, this means less dilution from capital raisings.

But finding gold deposits on greenfields projects is very hard.

For guys like Predictive, this means approaching exploration in a very technical way.

“We have a system which we call ‘Predictore’ and that system is built around doing a whole-of-country assessment,” Mr Roberts says.

“Typically, we will get hold of a countries entire GIS (geographic information system) database, and we will buy all the aeromagnetic data.

“We are looking for gold, so we are hunting for a particular class of deep structure that we think controls the location of gold deposits.”

Predictive is having success with its method, currently partnering with two companies including private miner Toro Gold.

Mr Roberts says it’s crucial to choose the right partner; partners that have the skills to take a project through to production.

“We want people with a history of building mines,” he says. “And for them to be focused on the project; you want the project to keep moving.

“You don’t want them to do a drilling program and then go back 18-months later and do another drilling program because you get nowhere, you get no traction in the market.

“You don’t have that consistent news flow.”

The joint venture agreements also give Predictive flexibility to make decisions as a project progresses.

For example, last year the company made the decision to conserve cash by reduce its equity in the Toro JV to 30 per cent (from 35 per cent) by not making any cash contributions in the December half.

It’s critical to be disciplined, and not to fall in love with your projects, Mr Roberts says.

“We have to make technical judgements all the way along.”

In 2016 when Predictive got its first high grade hits from the Boundiali project – part of the Toro JV — the share price ran up 10 times in the space of three or four months.

“We have fallen back significantly since then, but great results from anywhere in the portfolio can stimulate that kind of run again,” Mr Roberts says.

For day traders, there’s an opportunity to make money out of a company like Predictive, which have multiple projects on the go at once.

But the overall model is really for the patient investor, Mr Roberts says.

For the patient investors, there’s a few of ideal scenarios that could play out if a project reaches a development decision.

Firstly, the JV partner may decide the buy the prospect generator’s share of a project.

Most people who are building mines in West Africa don’t want the junior partner, Mr Roberts says.

“They want to maximise equity for themselves, so that gives us an opportunity to sell out of a project at a pretty good price and return that cash to our shareholders.

“That’s one scenario, and it’s repeatable.”

Alternatively, as is the case with the Toro deal, if Predictive get to the endpoint and don’t contribute there will be a royalty payment if a mine is built.

Royalties are wonderful things to have, Mr Roberts says.

“A significant operation can generate a lot of free cash, and our company will become valuable just because it is waiting for the cheque to come through each month.”

This could be a dividend stream for shareholders, or at the very least a way of sustaining the company.

But the really big endgame for a prospect generator is find a monster deposit – and go out with a bang.

“Find a tier one, sell yourself for $100s of millions to the company that wants to build this mine.

“Everyone who has invested in you makes an awful lot of money.”