You might be interested in

ESG

The Ethical Investor: These three ESG award-winning ASX companies show how it’s done

ESG

The Ethical Investor: COP29 pushes for 10x more climate funding, considers crypto levy to save planet

ESG

Explainers

ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) is a fast growing investment theme in Australia including on the ASX. Here’s a guide on what you need to know about ESG.

The Environmental, Social and Governance framework provides broad umbrella standards by which companies and their impact can be evaluated beyond traditional financial metrics.

The term ESG is often used interchangeably with “ethical investing” or “impact investing”.

However, this guide focuses on ESG as it relates to specific metrics and their application to listed companies.

The most obvious environmental impacts a company can make are energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. But other metrics that may only affect certain sectors, such as industrial waste and water consumption, are just as important.

Among major sectors it is easy to point the finger at resources and industrials, but tech and financial companies may still have a carbon footprint of their own.

Even some healthcare firms (particularly companies that use chemicals) can cause water contamination, soil depletion and biodiversity loss.

It’s complicated.

Unfortunately, for all but the largest companies, the most ethical investors can do is look at the impact of entire sectors – which is why there’s far more consensus on what should not constitute an ESG investment than what should.

It is easy to think of external activities such as charity donations as unrelated to a company’s core operations.

But elements of social impact are measurable within a firm’s operations, with two examples of social metrics being employee turnover and incident rates.

A company with high employee or management turnover likely has problems. A warning sign for now delisted companies Sunbridge Group and Bojun Agriculture were board members walking out and blowing the whistle on company troubles.

While disasters such as industrial accidents or data breaches can happen, often the way companies respond to them is a major factor.

For example, theme park operator Ardent Leisure (ASX:ALG) was widely condemned for its response to the Dreamworld tragedy.

Traditionally, the sole factor for governance is the ability to achieve profits. But governance now includes a wide range of metrics.

One factor, however, is the number of women on the board. In 2019, Stockhead found less than 24 per cent of small caps had at least one woman on their board.

A second factor is executive pay. This could be considered in isolation or compared to average employees. Alternatively, as a proportion of operating expenses, market cap or profit.

If it is too high, particularly in comparison to revenue, then it casts an unfavourable shadow.

Another negative sign for a company is if one individual executive or the board owns too much of the company. This is because it limits the power of all other shareholders.

At least some ESG factors have potential to impact a company’s bottom line.

As Morningstar analyst Adam Fleck told Stockhead last November, “I cover Coca Cola Amtil (ASX:CCL) for example and I have to consider the company’s water usage and the impact of potential sugar taxes as social factors for instance.”

“Those are just two risks in the company that are ESG by definition. But [they] are important in considering the ultimate future cash flow of the business.”

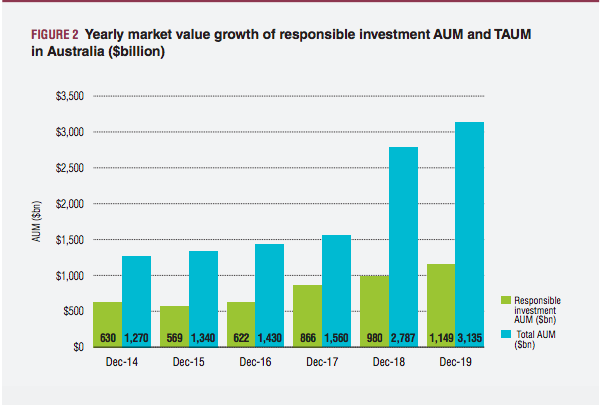

The global market for ESG-focused investments has seen high growth over the last several years.

Last September, the Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA) estimated that of Australia’s $3.135 trillion funds under management, $1.149 trillion was managed by “Responsible Investment Managers”.

This amount has nearly doubled in five years.

Another piece of evidence is the rapid growth of ESG-focused fund manager Australian Ethical Investment (ASX:AEF).

In the past two years the company’s ASX share price has more than tripled from $1.57 to $5.50. Furthermore, its funds under management recently surpassed $5 billion – well up from $2.85 billion in December 2018.

Looking globally, socially responsible investments surpassed $30 trillion back in 2019 – a spike of over 30 per cent in the two preceding years.

Additionally it is often argued that the rise of new markets such as electric vehicles and plant based meat and subsequent share price success are evidence that investors are looking towards societal impacts when considering their investments.

Since COVID-19, risk assets such as gold and government bonds have performed well.

Investors may arguably have been attracted by the solid performance of certain ESG funds.

Furthermore, it has been argued given how critical ESG analysis can be, ESG provides an extra safety net for investors.

Last year at the height of COVID-19, financial advisory firm deVere Group reported that 56 per cent of its clients that sought ESG-oriented investments cited financial protection as a reason for seeking them.

In April, as markets began their recovery from the COVID-19 hit in March, Rainmaker Information argued that during the preceding quarter an “ESG effect” added 1 per cent to ESG-focused super fund members’ returns.

Many ESG issues have come to prominence in the past couple of years, particularly around corporate governance and societal impact.

Australian Ethical CEO John McMurdo told Stockhead last week described it as a “seismic shift”.

“That broader cross broader section of Australia is more aware [of ESG issues] now than they were say 2 years ago,” McMurdo explained.

“They’re seeing the rolling out of bushfires, global pandemics and then ethical corporate governance issues – AMPs, Rios and others come to mind.

“I think now, you get investors going,’ Look, my money can do well and do good at the same time and so why wouldn’t I?’ This is what we’ve been observing.”

While there are some industries are “no go zones” for most ESG funds there’s less consensus on what constitutes responsible investing.

Even the RIAA has admitted as such to Stockhead.

The organisation focuses more on funds complying with their promises made to investors rather than judging them on industries they invest in.

This means investors have to look at each individual funds’ rules and judge for themselves if they agree with them.

The higher degree of scrutiny can also be a bad thing – it can lead to investors over re-acting to bad news in the short term.

This would lead to a larger fall in the share price than might be justified by fundamental financial considerations. It would also provide a chance for non-ESG focused investors to buy in.

In some instances, yes. Most obviously companies must tell the ASX of “material risks” to their company both financial and ESG-related.

But there are also a handful of operational standards that companies are legally required to meet. One example in Australia is the Modern Slavery Act, which requires companies with consolidated revenues of $100m or more to report annually on the risks of modern slavery in their operations.

Other ESG metrics can be implied from publicly available information such as if executives are overpaid relative to their company’s performance.

Companies may also have plans such as Diversity Policies but it is up to shareholders to keep them accountable.

The simplest way of measuring ESG impact right now is if the company publicly discloses it publicly.

Yet even when companies disclose them they may be difficult to sort for investors.

Some investment services such as Morningstar offer stock ratings based on ESG risks .

There have also been a handful of companies seeking to make ESG measurement easier, ranging from global firms such as Bloomberg to local start ups.

“It’s getting better [yet] I think we still have some way to go to be fair, but definitely improving,” Australian Ethical’s McMurdo told Stockhead.

As has been outlined above, there is evidence that ESG-focused funds can perform solidly and not just in tough times.

The RIAA found that in the 10 years to 2019, Australian share funds applying “responsible investment practices” produced a further 2.2 per cent return compared to the average return across all comparable funds.

ESG advocates often argue that they perform better because ESG metrics have potential to impact a company just as much a financial metrics.

But, in absence of a consensus on uniform ESG metrics, it is difficult to succinctly conclude this is always the case.

Nevertheless, some negative ESG events can cause poor performance.

A February 2021 study by Monash University found that since 1998, deaths of environmental activists caused mining companies with projects the deceased have targeted resulted in average share market losses of over US$100 million.

Currently, Australian Ethical Investment (ASX:AEF) is the only pure play ASX stock in ESG and it’s been listed since 2002.

There are also a handful of ESG-focused ETFs on the ASX. Some examples include:

Many of these netted positive returns for investors in 2020. The biggest winner was ETHI which gained nearly 24 per cent in 2020.