J.P. Morgan has weighed in on the Australia’s housing sector – a worthwhile side gig since Australian banks are most grievously exposed to house prices and interest rates as residential mortgages currently represent well over 60% of our banks’ total loans, one of the highest levels in the world.

JPM says thus far in ’22, the whole sector – housing prices, turnover and construction activity – are all showing signs of fatigue.

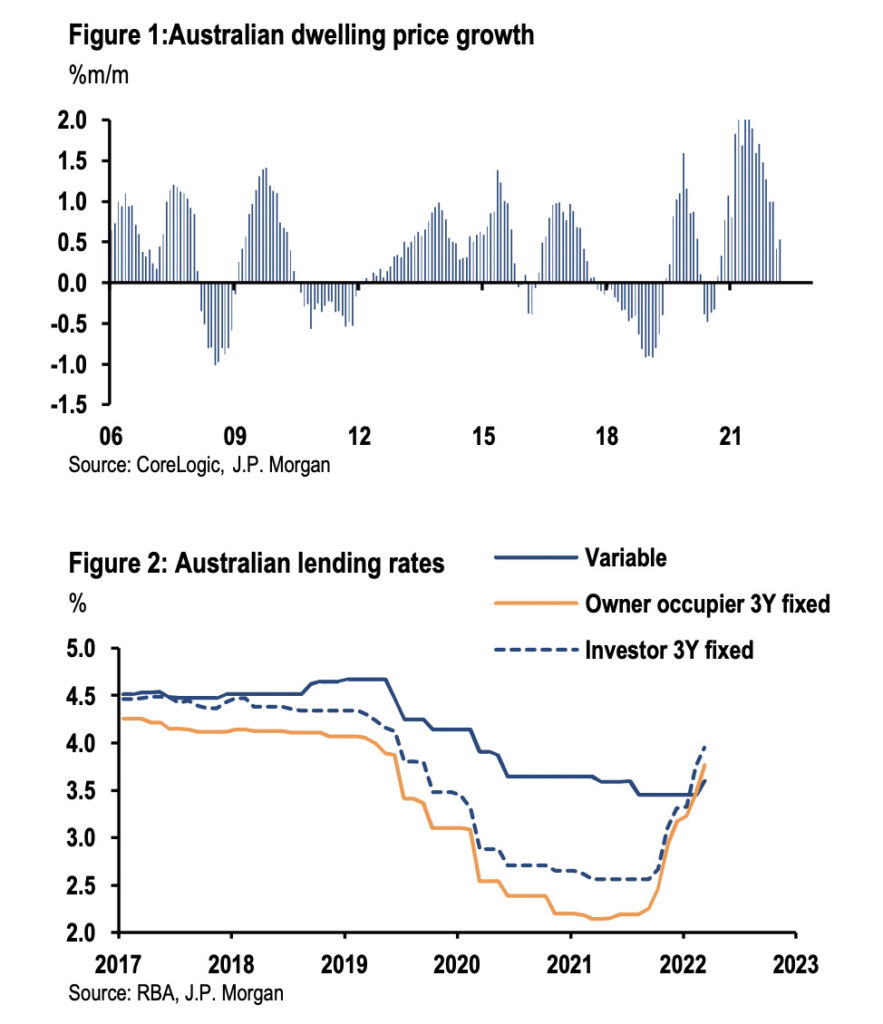

Monthly national house price growth remains positive, but the pace has slowed notably from last year’s peaks.

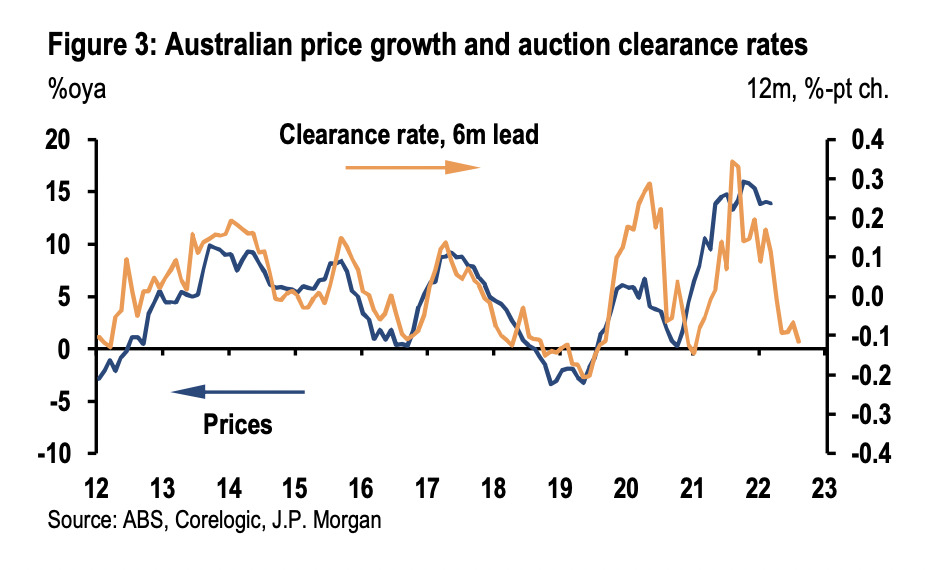

“The catalysts for this price deceleration are well known,” JPM analyst Ben Kennedy noted this week, “with rising fixed mortgage rates, the prospect of policy rate hikes from mid-year – J.P. Morgan’s forecast is +15bp in June – and the increasingly stretched affordability metrics weighing on housing demand.”

Certainly – and in the face of long-held protestations from the Reserve Bank (RBA) which this week left the notion that rates wouldn’t budge till 2024, a June rate hike is now considered most likely.

The market is pricing in rates lifting off in June, a total of eight rate hikes by the end of the year and 12 by the middle of next year.

Trouble ahead?

JP Morgan says the deterioration in housing metrics is perhaps most apparent in auction clearance rates which this weekend are hitting record volumes but concurrently are now running in the low 60% range, roughly 20% below this time last year.

“Total home sales (auction and private sales) remain elevated, but have also pulled back from the peaks and exhibit signs of waning demand.”

Sale volumes historically lead price growth by around six months.

Based on the most recent data prints, JPM says annual growth rates will converge to zero in the next six months, which implies an 8%-10% price decline from current levels, but with a rider:

“Admittedly this relationship has been less reliable through the pandemic (note the 2020 deviation) so we treat these estimates with caution, but acknowledge the directionality is clear.”

Supply constraints still bind

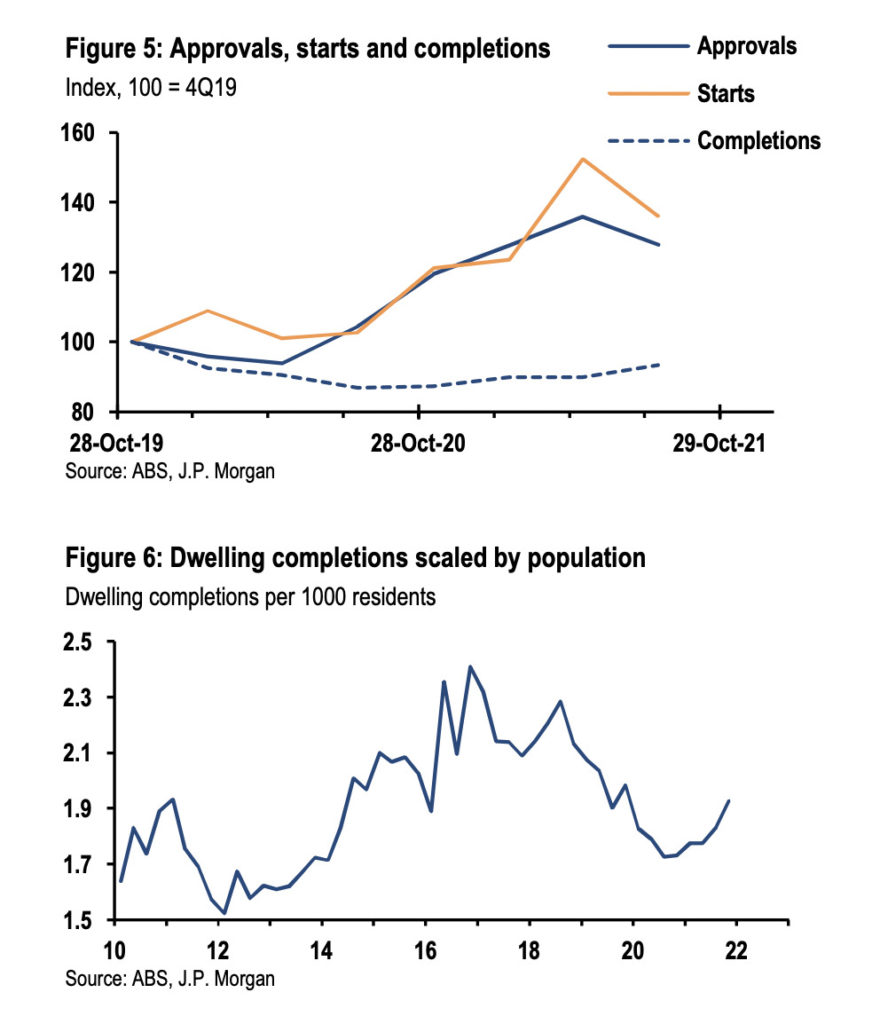

JPM notes, record low interest rates, a resilient labour market and elevated household savings were supportive for the construction sector through the pandemic, and underpinned the surge in building approvals commencing in late 2020.

“One interesting wrinkle in the data is that although approvals and starts have surged, dwelling completions have failed to launch and remain below levels recorded in 2019, a dynamic which highlights supply constraints hindering the construction sector. As a result, completions per head of population are now below 2019 levels despite migration flows essentially grinding to a halt.

“With that in mind, we do regard this as a timing issue and anticipate completions to move higher in 2022 as dwellings currently under construction are finally completed.”

In contrast to the prior construction cycle commencing in 2014, the acceleration in new dwelling construction has been concentrated in single family houses where project numbers have almost doubled compared to 2019 levels.

Higher density construction remains the larger sub-group of construction, and that’s been lagging the wider boom through the pandemic, thanks to weak population growth, some urban-to-rural migration and the old working from home (WFH) thing.

The composition of dwelling construction is important from a real GDP perspective given the impulse from detached dwellings to residential investment (GDP concept) is roughly double that of higher density construction, meaning the relative impulse from the current construction cycle to GDP growth will be larger than what was reported in the prior cycle.

Satyajit Das author of Fortune’s Fool: Australia’s Choices says that won’t matter much since our ‘astronomically’ high house prices ‘mask moribund wages and exacerbate housing unnaffordability.’ And unlike business investments, capital tied up in homes doesn’t do anything much for the economy, for lifting incomes or generating jobs.

According to the OECD, our household debt – primarily mortgages – is currently around 130% of GDP, among the highest levels globally. Household debt to disposal income is over 200%, compared with 50% in the 1980s.

And even during the record-low interest rates which we are now bidding goodbye – Das warns over 13% of income is still used to service this debt. The crazy thing here, is that number is higher than in 1989—90 when interest rates peaked at nearly 20%.