We spoke to Kuniko chairman Gavin Rezos before the battery metals explorer’s bonkers Thursday

Mining

Mining

Kuniko, the Norwegian base metals exploration spinoff of lithium market darling Vulcan Energy Resources (ASX:VUL), listed on Tuesday.

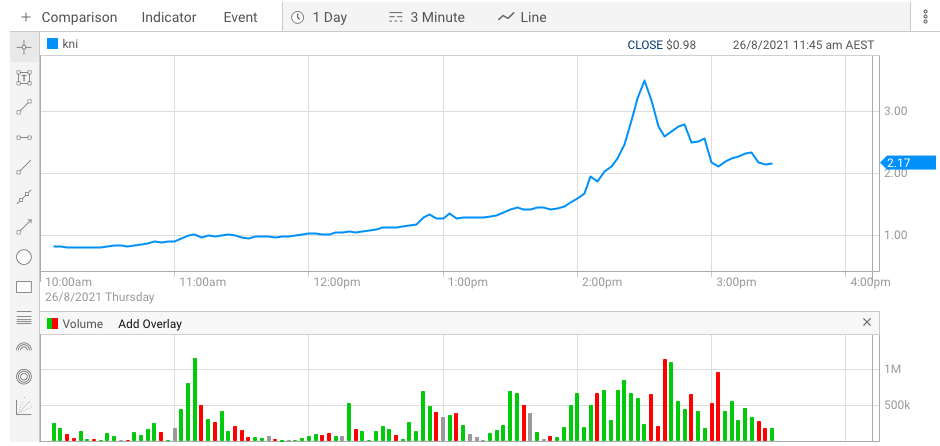

Then it made a pretty basic post-IPO ‘we’re starting exploration’ announcement and did … this?

The stock ran above $3.50 during trading yesterday, more than 17.5 times higher than its issue price of 20c, before retreating swiftly to $2.17 (a 183.7% gain).

“I lost 50% of my money trading $KNI today. THE MARKET IS RIGGED.” https://t.co/oGccQUrj3L

— Assad Tannous (@AsennaWealth) August 26, 2021

That unsurprisingly caught the eye of the ASX, which issued a speeding ticket and forced Kuniko into a trading halt. We’ll see how that turns out when the company comes forward with its explanation.

While Vulcan was once focused on Norse minerals in its old guise as Koppar Resources, the assets the geothermal lithium company has folded into Kuniko are largely distinct from the ones it used to hold.

They’ve been replaced by copper, nickel and cobalt projects (Cu-Ni-Co, geddit?) featuring centuries-old mines due to be looked at through a new, battery metals, ESG lens that jives with (25.8% owner) Vulcan’s “zero carbon” brand.

Those include the two projects where exploration began yesterday, Vangrofta and Skuterud, the latter of which was once Norway’s largest company and the world’s biggest producer of cobalt, turning out 1Mt of the rare metal between 1773 and 1898.

Stockhead spoke to Kuniko chairman Gavin Rezos this week (before yesterday’s madness) about the explorer’s strategy and its future plans.

“So these projects are not the same ones that Koppar had. So when, when Francis, Horst and I went into Koppar and the board changed, we reviewed the Norwegian projects and we did extra work on them, as required by ASX of course, and to make sure that we give them full value.

“But the geothermal was the main play for us from that point and … two of the three projects that Koppar had we let go and one we’ve kept on.

“We had resources in Norway, and we had connections there. We had some of the geologists go out and look for other ground which would suit the battery metals thematic a bit more strongly, bearing in mind the long, long history of mining in Norway.

“So we looked into those sort of areas to see what was available and applied. And that’s the Vangrofta copper project and the Skuterud cobalt project in particular.

“The old projects that we had, in fact, have ended up in Canadian companies, EMX took them on for a royalty. That shows that even the last three years people realize just how important Norway’s becoming from a minerals perspective.”

“Well, first thing, you’ve got to look at the speed of the change. Two things are happening.

“One is Europe is changing rapidly in relation to trying to get a sustainable supplier of ethically sourced battery metals. The other aspect is that Europe for a long time wasn’t really interested in mining. It’s very hard to do mining in most of Europe.

“In Norway they were making so much money from North Sea oil that mining became secondary for the economy.

“On a per capita basis, they produce the most petrocarbons per capita in the world. And so they’ve suddenly realized this is not a good look.

“Over the last two years, particularly, we hear Norwegian ministers and the talk about the need to switch from the petroleum industry and get those workers across probably to a mining industry.

“So the beauty of it is that there are mines that are still operating … but there’s a lot of these old mines all around that as you said are up to 400 years old. In fact, Skuterud was the biggest company in Norway in the 18th century and the biggest earner for Norway.

“Currently part of it is a tourist mine, but that’s only a small section of the strike length. So we’ve actually picked up all around the old tourist mine and don’t forget in those days you only went down to a maximum 100m before the technology stopped.

“Some of the other areas like Vangrofta, it’s simply a question of what the copper price was in the 1970s relative to these days.”

“That’s one of the great things here. So, it’s got the best renewable energy per capita as well, in terms of wind and hydro, hydro in particular.

“And you’ve also got just across the border in Sweden, probably the most advanced groups in mining, using electrifying equipment.

“So in Kiruna the groups there that have been mining iron ore underground, using EVs, EV trucks for some time and drilling equipment.

“So in terms of making this a company which is zero carbon on the basis of hydropower, electrified drilling equipment, trucks, vehicles, etc, we’re in a very good place to do that.”

“The mining industry has been very slow. Three years ago at, a London mining conference, I raised the issue of carbon footprint, and everyone thought I had two heads.

“They took the view that, well, it’s mining, therefore, it has a carbon footprint. So like we were the first ones at Vulcan to do lifecycle analysis on our footprint, and other companies are starting to really imitate what Vulcan has done, you’ll see zero carbon, neutral carbon used willy nilly.

“I’ve seen companies put promotions up to say they opened up zero carbon in the middle of Africa – it’s impossible. They can be carbon neutral. They can buy offsets by investing in forests or carbon sequestration but they cannot be carbon neutral if they have no renewable source of energy and they’re trucking in the middle of Africa.

“It’s physically possible, so everyone wants to get on the bandwagon, but that doesn’t mean that just by saying that you are.

“You have to demonstrate it, and particularly in Europe, if you say you are and you can’t demonstrate it there are regulatory consequences. So, being able to be carbon neutral, zero carbon and battery metals, and then the right place, right time, right country is what is the attracting investors to the potential of Kuniko.”

“There is an acceptance even though in other parts of Europe, it’s not in my backyard, the community was here first, in Scandinavia there is a recognition that people must do their part.

“And one is that it’s not good to just drive around in your EVs with your wind power and your hydropower, if you’re getting your battery metals and rare earth magnets from African mines which are not ethically sourced.

“So they also recognise that Europe needs secure supply. So where is the supply? Well it’s in Scandinavia.

“And so Norway has a much higher level of citizen acceptance of the need for mining than the rest of Europe. That doesn’t mean to say that they agree to having it in their backyard, but it is an easier process.

“The mining regulations are modern in Norway and there’s no surprises. There’s things you have to do. And it’s a process to do them.

“It’s much, much better than operating in other parts of the world where you’re not sure what you own from one day to the next.”