You might be interested in

Mining

Monsters of Rock: Second big bank upgrades gold forecasts. Can miners catch up?

News

Hot Money Monday: 'Cut losses and let winners run' - advice from legendary momentum trader Paul Tudor Jones

News

Mining

Dysprosium has been labelled the “dark horse in the rare earth stakes” as the rapid growth in the electric vehicle market spurs higher projections for demand of the magnet metal.

The heavy rare earth is an additive used in the permanent magnets required for the motors in electric vehicles.

Dysprosium reduces the weight requirement and allows operation at very high temperatures.

Each electric vehicle contains roughly 100 grams of dysprosium.

In a recent research report, Hallgarten and Company likened the rare earths space to a horse race.

The firm said it has been perceived as a “two-horse race” between fellow magnet metals neodymium and praseodymium, but that perhaps dysprosium was discounted a little too quickly.

“One of the horses that should not have been scratched from the race though is dysprosium as it is still up and running and dare we say it, racing up on the outside and potentially giving those wagering on deposits slanted towards dysprosium their moment of glory in the Winner’s Circle,” Hallgarten and Company said.

There are more pluses than minuses for the dysprosium market — the key factors are a growing supply shortage, higher electric car production and very little chance of substitution.

The International Energy Agency expects electric vehicles on the road will number 125 million by 2030.

If policy ambitions continue to rise to meet climate goals, the number of electric vehicles could be as high as 220 million in 2030.

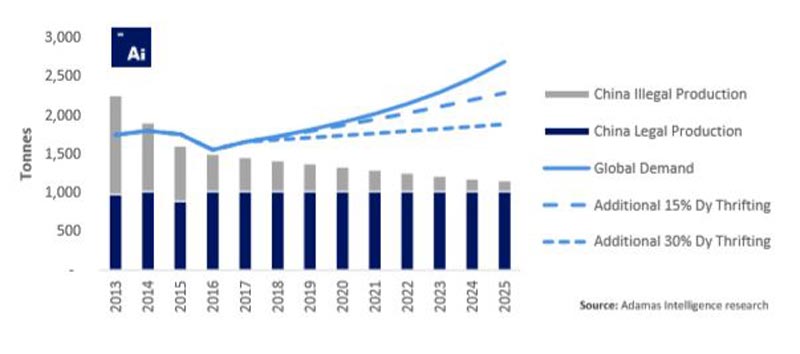

Adamas Intelligence said earlier this year that China’s ongoing government-led crackdown on illegal rare earth mining has led to a 34 per cent drop in global dysprosium oxide production since 2013.

The market researcher believes that China’s production alone will be insufficient to support global demand growth.

The forecast is that by 2025, China’s demand for dysprosium oxide for electric vehicle traction motors alone will amount to 70 per cent of its current “legal” production.

Adamas Intelligence says even with a further 30 per cent reduction in dysprosium usage (see chart below) by the magnet industry, the outlook is concerning.

Particularly given that by 2025 electric vehicle traction motors are tipped to become the single largest end-use of dysprosium oxide globally.

Adamas estimates that demand will reach over 2,500 tonnes by 2025 compared to just over 1,500 tonnes at the moment, while legal Chinese production will remain steady at about 1,000 tonnes.

At the moment Northern Minerals (ASX:NTU) is the only ASX-listed heavy rare earths producer outside of China.

There are heavy rare earths and light rare earths. Heavy rare earths have a higher atomic weight than light rare earths.

Northern Minerals’ 60,000-tonne-per-annum Browns Range project in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia produces primarily dysprosium and terbium.

Both commodities are considered critical metals because of supply constraints and their importance in the development of clean energy technologies.

The Browns Range project is expected to produce 280 tonnes per annum of dysprosium oxide.

Greenland Minerals (ASX:GGG) is also aiming to be a dysprosium producer from its wholly owned Kvanefjeld project in Greenland.

It is projected to be one of the largest producers globally of key magnet metals including neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium, along with by‐production of uranium and zinc.

In September, Greenland Minerals lodged an updated environmental impact assessment for the Kvanefjeld project, which is expected to produce 245 tonnes per annum of dysprosium oxide.

Alkane Resources (ASX:ALK) will also produce dysprosium oxide — around 125 tonnes — from its Dubbo project in New South Wales.

Government approvals have been in place for the start of the $1 billion Dubbo project for some time, but the difficulty has been in securing financing and offtake agreements.

Alkane has been waiting for a lift in zirconium prices to give the project the green light. Zirconium will account for 40 per cent of output.