Vanadium stocks guide: Here’s everything you need to know

Explainers

Vanadium is a battery metals firecracker right now, with the price continuing on a rapid upwards trajectory. Here’s a look at how vanadium stocks have become so popular, what’s driving the demand and key ASX-listed companies to know.

It’s taken a while for investors to realise the potential of vanadium in the battery metals race, but interest is starting to pick up.

While EV production is a hot topic, stationary energy storage applications – where vanadium is needed, has industry experts particularly excited.

Stationary storage systems are big batteries often designed to store excess power from the power grid — including from renewable sources — for use during expensive peak demand periods.

BloombergNEF says energy storage applications around the world will multiply exponentially from a modest 9GW/17GWh in 2018 to 1,095Gw/2,850GWh by 2040, marking a 122-fold boom over the next two decades.

Vanadium producer CEO Fortune Mojapelo says if vanadium redox flow batteries capture just 10pc of the stationary battery market, by 2030 global production of vanadium will need to increase by as much as 50pc.

The outlook is big but while vanadium is set to become a key resource in the fast-growing battery sector as part of the renewable energy mix, most of its consumption (around 90pc) is used to strengthen steel.

Of the remainder, vanadium is used in aerospace alloys and chemical catalysts, and 1pc goes into vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs), which are regarded as a safer alternative to lithium-ion and better suited to large-scale applications.

They come at a higher upfront cost but have a far longer life compared to lithium-ion batteries.

In this guide, Stockhead explains the factors that have been driving vanadium stocks, and what will spur demand — and stock prices — into the future.

Most vanadium is used in steel-making. Over 90 per cent of the commodity is added to steel to make it stronger.

Vanadium was initially discovered in 1801 by Spanish scientist Andres Manuel del Rio — who called it “erythronium” at the time.

The commodity was forgotten about until Swedish chemist, Nils Gabriel Sefström, happened across the mineral in 1830 and it finally got the name vanadium — the Scandinavian goddess of beauty — because of the beautiful colours of its compounds in solution.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that vanadium’s considerable strength was discovered.

That made it the material of choice for things like planes, cars and buildings.

Vanadium started to be used industrially over a century ago, with its first application being in the vanadium-steel alloy chassis of the Ford Model T car.

But it hasn’t been until the last few years that the excitement around vanadium has really taken off.

The reason for that is its application as a battery metal. Vanadium is the key commodity in what is known as a “flow” battery.

Vanadium redox flow batteries (or VRFBs) are better suited to large scale applications (stationary storage), such as network support for electricity grid operators and telcos looking to power off-grid communications towers and utility scale installations.

Vanadium batteries are safer than lithium-ion batteries, cheaper than other types of “flow” batteries, and have the longest life spans, lasting more than 20 years or up to 25,000 cycles.

They require little maintenance and can be fully discharged without damage to their storage capacity.

They use two tanks of vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) solution that have been processed into a liquid electrolyte.

When the electrolyte is pumped through electro-chemical cells past a proton-exchange membrane, ions are swapped between the negatively and positively charged electrolyte, creating an electrical charge.

The VRFB is inherently more stable than lithium-ion because the electrolytes are just positively and negatively charged versions of the same chemical and the process of charging and discharging does not generate excess heat.

The vanadium battery technology is an Australian invention and the first prototype was built by Maria Skyllas-Kazacos at the University of New South Wales in the 1980s.

But it wasn’t until about three years ago when the commercial rollout of these vanadium batteries started to ramp up and investors began to sit up and take notice.

Now these big batteries are a reality in Japan, China, Australia and soon to be in Germany.

In China, Rongke Power in Dalian province is building the largest battery in the world, an 800MWh VRFB, while in Hebei province Pu Neng Energy is building a 500MWh version.

Germany is looking at building a VRFB that can store enough energy to power Berlin for an hour, which would be a big step forward from the Tesla lithium-ion battery built in Australia which only has the capacity to provide 2 per cent of Adelaide’s power requirements at any time.

In August 2018, small cap vanadium player Protean Energy (ASX:POW) successfully hooked up a 25kW/100kWh vanadium battery with Western Australian electricity operator Western Power.

Protean has been developing its V-KOR VRFB for about 10 years with Korean partner KORID Energy.

VSUN Energy, meanwhile, launched WA’s first VRFB in 2016.

Vanadium is largely a by-product of a bunch other minerals. It rarely occurs in nature by itself.

There are only three large-scale primary vanadium producers globally – Bushveld Minerals, Glencore, and Largo Resources.

The world’s largest vanadium mines are found in the Bushveld region of South Africa, the Ural Mountains of Russia and in China’s Sichuan province.

Even with planned expansions by existing producers designed to increase annual production, the supply shortfall is expected to widen further as demand for vanadium continues to rise.

When it comes to vanadium it is not just as simple as looking at the grade of the ore.

The keys to determining a good deposit come down to the overall magnetite recovery and the grade of the vanadium you get from that magnetic concentrate.

Canada’s Largo produces the highest-grade V2O5 in the world of 3-3.2 per cent from its Brazilian mine.

But it does that from a typical magnetite recovery of 30-35 per cent, which is considered pretty good.

The Rhovan mine in South Africa’s Bushveld Complex also has a 30-35 per cent magnetite recovery and it produces 1.6-1.8 per cent V2O5.

There are four main uses of vanadium.

Traditionally, vanadium is used in:

Steel – 90 per cent of vanadium is used in steel. It takes only a small amount of vanadium to double the strength of steel and reduce its weight by 30 per cent.

Titanium – vanadium is also used to make titanium alloys. This is where titanium is mixed with other chemical elements to make it stronger. Titanium alloys are used in military applications, aircraft, spacecraft, bicycles, medical devices and jewellery.

Chemicals – V2O5 is used in ceramics and as a catalyst for the production of sulfuric acid.

Growing demand for steel, particularly in China, has driven a shortfall in the commodity.

But all the excitement in recent years has focused on vanadium’s use in batteries for stationary energy storage.

While the electric vehicle space is firmly dominated by lithium-ion for the moment, stationary storage is more diverse.

There are a couple of battery technologies vying for top spot, but the spotlight is largely on VRFBs.

Benchmark predicts that by 2028, 50 per cent of the burgeoning stationary storage market will be lithium-ion, and 25 per cent will be VRFBs.

“The area where you are likely to see far more variation in battery technologies is stationary storage applications where you don’t need the lightweight benefits of a lithium-based technology,” Benchmark senior analyst Andrew Miller told Stockhead.

“While we still expect lithium-ion to play a big role in this market there will be several other technologies that compete for market share in this space.

“For stationary storage, vanadium flow is very interesting because of the life-cycle advantages and the fact that the input raw materials can be reused.”

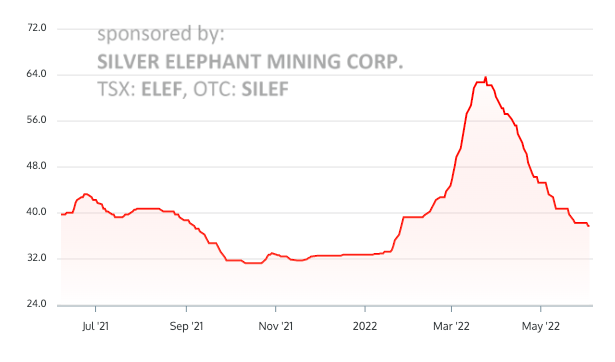

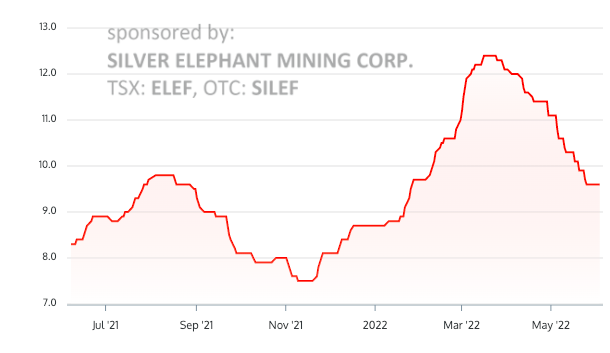

The price of V205 hit its highest point in 13 years reaching $US32.50 in October 2018.

The price came off an all-time high in 2005 before going for a run again in 2008. It levelled out to trade pretty well flat between 2009 and 2015 before taking off again in 2016.

Though the price has picked up in 2022, it can be volatile as the price is captive to both Chinese steel production (with China being one of the biggest steel producers in the world) and the iron ore price cycle given most vanadium production is in the form of ferrovanadium as a steel alloy input.

Vanadium demand for VRFBs is growing at a rapid rate. The forecast compound annual growth rate for vanadium to be used in VRFBs is 60 per cent.

Current demand is about 100,000 tonnes per annum, but that is tipped to triple over the next five to six years.

Benchmark boss Simon Moores says vanadium could have its “Elon Musk moment” as it advances towards powering 25 per cent of stationary battery storage by 2028.

“The potential for vanadium flow is absolutely significant,” Moores told delegates at an industry event earlier this year.

“If the vanadium market gets a number of key [mines] up and running quickly, vanadium flow could have its ‘lithium-ion battery moment’ — its Elon Musk moment.”

The man himself, Musk, said at a shareholder meeting earlier this year that “the rate of stationary storage is going to grow exponentially”.

“For many years to come each incremental year will be about as much as all of the preceding years, which is a crazy, crazy growth rate,” he said.

Lux Research forecasts that vanadium flow batteries will be at the very least a $190 million market opportunity by 2024 and on an “optimistic” basis will be well over $400 million.

Steel demand is also on the rise.

Railway construction is also now becoming a significant factor in steel demand as China ramps up its One Belt, One Road policies.

China’s One Belt, One Road is multi-trillion-dollar initiative to build efficient trade corridors between China, Asia, the Middle East and Europe. It involves new rail, road and maritime infrastructure in some 70 countries.

The expectation is that this year railways in China alone will consume 32 per cent of the country’s total steel demand – around $US26 billion worth of steel.

And that doesn’t take into account the railways China is building outside of the country.

There are about 40 ASX stocks with exposure to vanadium.

Here are the top four by market cap:

Market cap: ~$1.1bn

Syrah is the largest player by market cap, but it is primarily a graphite producer.

The company, however, is investigating the possibility of also producing vanadium from its Balama operation in Mozambique which started production in late 2017.

According to Syrah, Balama “contains a significant vanadium by-product resource which presents a potential value-accretive opportunity” which the company will advance through pre-feasibility study (PFS).

Market cap: ~$693m

Neometals wholly owns the Barrambie Titanium and Vandium Project in Western Australia, which has a granted mining permit and has been the subect of roughly $30m in NMT exploration and evaluation expenditure since 2003.

NMT is working towards a development decision in December 2022 with potential operating JV partner IMUMR and potential cornerstone product offtaker, Jiuxing Titanium Materials Co.

It also has a 27-month option to evaluate establishing a 50:50 joint venture to recover vanadium and substantially produce vanadium chemicals from processing by-products (slag) from leading Scandinavian steelmaker SSAB.

Neometals’ has a collaboration with Scandinavian mineral development company Critical Metals to jointly evaluate the feasibility of constructing a recycling facility to undertake this work.

Market cap: ~$173m

Australian Vanadium has a portfolio of vanadium assets including the Coates project, Blesberg lithium-titanium project and Nowthanna Hill uranium-vanadium project but its flagship project is the Australian Vanadium Project, located in Western Australia’s Murshison region.

The project was awarded Federal Major Project Status by the Australian Government in September 2019 in recognition of its national strategic significant and State Lead Agency Status in April 2020 by the Western Australian Government.

A Bankable Feasibility Study in April revealed the project would achieve annual vanadium production of 24.7Mlb V205 as a 99.5% V205 high purity flake and 900,000 dry tonnes per annum iron-titanium co-product.

Market cap: $94.4m

The $94 million TNG is working to bring its $850 million Mount Peake vanadium, titanium, and iron project in the Northern Territory into production, which has received Major Project Status by the Australian Federal Government as well as the Northern Territory Government.

The company is targeting production of up to 6,000 tonnes per annum of high purity vanadium pentoxide from Mount Peake, in addition to titanium dioxide pigment and iron ore fines products.

Mount Peake is a shallow, flat-lying orebody with a JORC measured, indicated and inferred resource totalling 160 million tonnes grading 0.28% vanadium pentoxide, 5.3% titanium dioxide pigment and 23% iron oxide.

Market cap: ~$86.5m

The company’s primary exploration focus has been on the Murchison Technology Metals Project, around 40km southeast of Meekatharra in WA’s mid-west region with the aim to potentially supply high-quality V2O5 flake product to both the steel market and the emerging VRFB market.

A key differentiation between Gabanintha and a number of other vanadium deposits is the consistent presence of the high-grade massive vanadium – titanium – magnetite basal unit, which results in an overall higher grade for the Gabanintha Vanadium Project.

However, during the March quarter, TMT advanced work on the Integration Study designed to combine the Yarrabubba Project (Yarrabubba) with the Gabanintha Project, which will be named the Murchison Technology Metals Project (MTMP).

TMT said Yarrabubba’s higher vanadium grades in concentrate (than Gabanintha), combined with the ability to produce a highly sought-after ilmenite by-product from Yarrabubba, indicate the potential to enhance the economic metrics in the early years of the project, lowering the risk of the full MTMP development.

The company also extended and expanded the scope of the MoU with leading Japanese VRFB development company, LE System, for the development of a fully integrated downstream vanadium electrolyte industry in Australia.

Names keep popping up when it comes to stocks to watch.

Critical Minerals Group managing director Scott Drelincourt told Stockhead the company’s Lindfield vanadium project in northwest Queensland is perfectly placed to ride the wave for the energy transition.

The 295sqkm project is just outside Townsville where the Queensland Government is funding and building a vanadium processing facility – which should be up and running in 2023.

Early in 2018 explorer Pursuit Minerals (ASX:PUR) picked up projects in northern Finland and Sweden.

In 2020 the company shifted its strategy to focus on Western Australia with the acquisition of the Warrior PGE-nickel-copper and Gladiator Gold Project.

Aura has defined a vanadium resource at its Tiris project in Mauritania that could significantly reduce the effective cost of producing uranium.

The company has defined a 18.4 million pound resource after confirming a consistent vanadium (V2O5) to uranium (U3O8) ratio exists within carnotite minerals, the primary host of uranium mineralisation at Tiris.

Adding further excitement – 34% of the resource is classified under the high-confidence Measured and Indicated categories.

AEE also owns the Häggån Vanadium-Uranium Project in Sweden with resources totalling 42Mt at 0.35% V2O5 and 800m pounds of U3O8.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Critical Minerals Group and Aura Energy are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.