Iron ore prices are coming back down to earth — but how far will they fall exactly?

Mining

Mining

Booming iron ore prices have been one of the main storylines in commodity markets this year.

The sharp rise led to a bumper profit season for Australia’s big miners, record trade surpluses and a timely boost to the federal budget’s bottom line.

But as the Deloitte commodities team noted in their latest outlook report, “all good things come to an end”.

The initial supply-side shock — largely caused by the Vale dam disaster in Brazil on January 25 — combined with a strong summer construction season in China helped drive benchmark prices above $US120/tonne ($174/t).

However, those dual forces are now “simultaneously unravelling”, Deloitte says. Prices are back down below $US90/t, and the key question that remains is whether or not prices have found an equilibrium.

Among the experts, the consensus view is that while global supply bottlenecks are slowly normalising, doubts remain about the outlook for Chinese demand.

Deloitte highlighted a trio of increased risks: “recent factory data disappointing, a property sector experiencing slowing growth, along with economic headwinds from the US trade dispute”.

And Ian Sanders, Deloitte’s lead partner of mining, said it’s a “sobering lesson of how quickly things can change in a volatile asset class like commodities”.

“With miners warning on the 2020 price outlook, iron ore is exhibiting all the elements of a failed soufflé, promising the world but ultimately falling flat on closer inspection.”

In that environment, analysts have been focused on trying to gauge the forthcoming intensity of this year’s winter production cuts.

ALSO READ: Which commodities cross the line into 2020 as winners?

For Glyn Lawcock and the UBS commodities team, the risk of reduced winter demand is “skewed to the downside”, when considered in the context of record production levels that took place in the first half of the year.

However, UBS said despite those concerns, early indications out of China are that this year’s production slowdown is unlikely to be historically steep.

For starters, a higher number of Chinese mills now comply with lower-emission standards, leaving them exempt from cut-backs.

In addition, China’s Ministry of Ecology & Environment has left emission-reduction decisions in the hands of regional councils “instead of a blanket policy, which is seen as more restrictive on output”.

The net result is that UBS expects benchmark iron ore prices to hold at an average of $US95/t through to the end of this year — higher than current levels of around $US87/t.

The bank cited the recent introduction of non-conventional “high-cost” suppliers (such as mainland Chinese miners) as one factor putting upward pressure on prices.

Longer-term though, UBS expects prices to recalibrate towards $US80/t next year, at the lower end of Deloitte’s “consensus view…for iron ore prices to trade at a more sustainable $US80-$US90/t in 2020”.

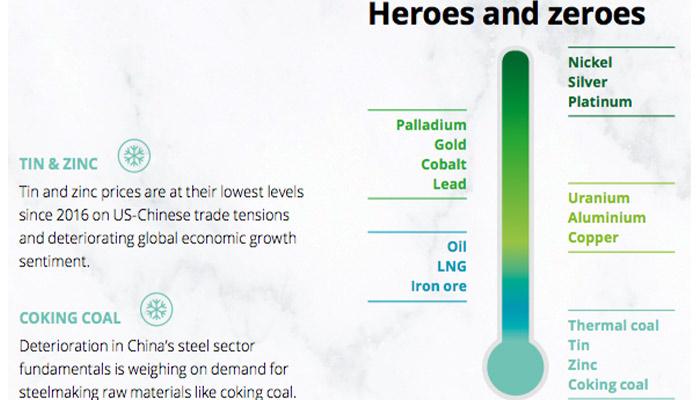

Looking at the space more broadly, Deloitte summarised which commodities are hot or not with the following thermometer:

In addition to his analysis of the iron ore market, Deloitte’s Sanders highlighted two other notable themes in this year’s outlook — the ongoing US-China trade war and the recent strength in gold prices.

“It is no exaggeration to call out trade tensions as the single biggest influence on commodity markets and the wider economy today,” Sanders said.

The next key date for commodity investors to watch for is mid-November, with expectations building that the US and China can reach agreement on the first phase of a trade deal before the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meetings in Chile.

“This will be a very positive development for metals demand and pricing, albeit one reserves judgment until a deal is fully locked in,” Sanders said.

Even if the two superpowers continue to push towards an agreement, Sanders said the fundamentals that had driven this year’s rally in gold — lower global interest rates, lingering recession fears and a pivot by global central banks to expand their reserves — should help to underpin prices.

However, “an earlier than expected resolution to the trade conflict could erode some of that safe haven support and send investors elsewhere in search for better returns”, he concluded.