Could Novo reignite the Pilbara conglomerate gold story?

Mining

Mining

“Conglomerate gold” in the Pilbara became all the rage back in 2017. But just as fast as investors piled into the story, they fled when they realised just how hard it was to turn these coarse nuggets into dollar bills.

Conglomerate gold refers to nuggets hosted in rock containing rounded grey quartz pebbles and other minerals. Conglomerate gold in the Pilbara is typically nuggety.

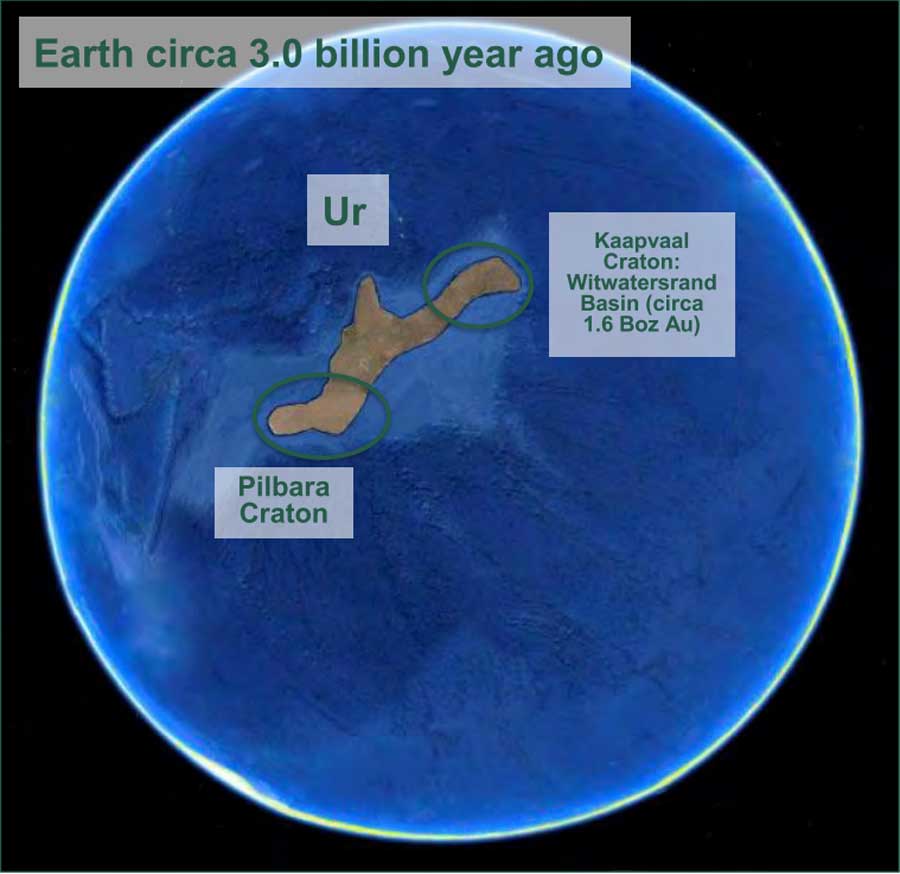

The world’s most productive gold region, South Africa’s Witwatersrand Basin, is famous for its similar geological formation, which has produced over 2 billion ounces — or about half the gold ever mined.

The story gained traction in late 2017 after TSXV-listed Novo Resources, during a presentation at the Denver Gold Forum, crossed to a live video of prospectors digging nuggets out of the ground at Purdy’s Reward south of Karratha in WA – a JV with Artemis Resources (ASX:ARV).

For Novo CEO Rob Humphryson, the fact “you could walk along kilometres of this stuff with a metal detector and make it sing” is what got him excited about the story.

This is a familiar comment, with Johnathon Campbell — the prospector that says he was the first to realise the conglomerate-hosted gold potential of the Pilbara — telling Stockhead previously that he and his crew found “thousands and thousands” of gold nuggets.

“If you turned on a metal detector you weren’t walking anywhere because there was too much gold,” he said.

Humphryson says conglomerate-hosted gold and it’s erosional remnants is a “basin-wide” possibility.

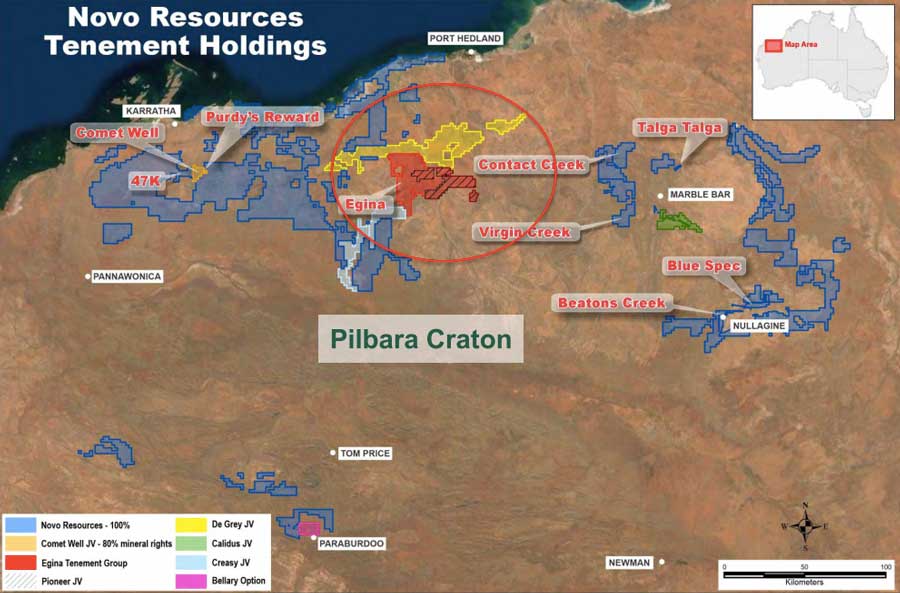

“Our geological model is saying that erosional remnants of gold bearing conglomerates could potentially go from Egina to the coast and to Karratha and Port Hedland, it’s kind of large,” he told Stockhead.

“It’s the same model as diamonds in Namibia. It’s just an extensive deposit that ran for hundreds of kilometres up the coast down to South Africa. So we’re looking at something that’s large.”

Then there’s the actual conglomerate-hosted gold itself – back in 2017 there was only really three known occurrences where conglomerate gold had been mined on a small scale – Beatons Creek at Nullagine and Tassie Queen and Just in Time near Marble Bar.

Today there are dozens of known occurrences of gold in conglomerates around the Pilbara, from near Paraburdoo in the south to Karratha in the north and across to Marble Bar and Nullagine in the east.

However, the thing that saw most explorers exit the hunt was the fact that the gold nuggets in the Pilbara were a lot coarser than those in the Witwatersrand Basin, meaning drilling wasn’t going to cut it. Bulk sampling was deemed the most effective way of working out grade and size. But that’s costly.

“To actually identify, dig and process a bulk sample you’re looking at around $10,000. I’m talking about a big sample, 5 tonnes or more,” Novo general manager of exploration Kas De Luca told Stockhead.

“So, it’s not something that if you’ve only got a little million-and-a-half-dollar budget you really can afford to be doing.”

While most other junior explorers have given up on the hunt and investors aren’t batting an eyelid at the story anymore, Novo has continued to drive its conglomerate-hosted gold projects towards production, which it hopes will be very soon.

“We would like to get into production within one year. As crazy as that sounds, we think that’s achievable,” Novo chairman and president Quinton Hennigh told Stockhead from his US home state of Colorado this week.

Hennigh is a well-known geologist, with around 25 years of experience, having worked for gold majors like Homestake Mining — which was eventually acquired by Canadian heavyweight Barrick Gold, Newcrest Mining (ASX:NCM) and Newmont Mining.

It was during his time with Newmont though that he was tasked with finding “Witwatersrand lookalikes” in other parts of the world.

There is some evidence that South Africa’s Kaapvaal Craton and the Pilbara Craton were once part of the same continent and over time split apart.

That led Hennigh to the Pilbara, where he did work for Newmont initially before branching out and acquiring ground of his own – starting with Beaton’s Creek, which he picked up from legendary prospector Mark Creasy around nine or 10 years ago.

Novo now has the largest conglomerate gold landholding in the Pilbara, has defined an inferred and indicated resource of 900,000oz at its Beaton’s Creek project and is on the cusp of field trialling mechanical sorting later this year as a path to production.

The reason Novo has been so well positioned to continue advancing its conglomerate-hosted gold projects is because at the height of the investor flurry into these particular stocks, the company attracted one of the world’s most prominent resources investors – Canadian billionaire Eric Sprott, via his company Kirkland Lake Gold.

“The excitement we had around the Karratha story back in 2017 helped us attract a large investment from Kirkland Lake,” Hennigh said.

“At the time we had maybe $15m in the bank. Kirkland Lake put in another $56m. That gave us a lot of runway towards it.

“This bulk sampling and all the hard science that we’ve had to do was paid for out of that. So we’ve had the luxury of having sufficient capital to do the hard science and get to where we are. No other junior companies have had that sort of luxury.”

Novo employs around 70 people in Australia, spends about $25m a year on exploration, and still has around $30m in the bank and no debt.

“The initial excitement was around the potential size and scale and so forth of this, but then when it became clear that we as Novo had to do a lot of hard work, in other words bulk sampling and things like this, I think the story got diminished somewhat because it’s not a quick and easy story,” Hennigh explained.

“We can’t just go out and drill a couple of hundred holes and say we have a 10-million-ounce deposit. It takes time, effort and good science.”

Novo’s hard work and “good science” has led to it buying a mechanical sorter, which is proving effective in lab tests and is a lower cost option than traditional processing.

Humphryson describes it as a “high-speed metal detector that can flick the nuggets out of a pile of rock”.

“We’ve done extensive testing with Steinert and TOMRA in Perth, Sydney and Germany with both of them to look at the size of nuggets that we can see,” he explained.

“Now two years ago they reckoned it wasn’t worth putting anything through a mechanical sorter of less than 6mm. We’ve since done work that shows that you can scan and detect and blow nuggets down to 0.6-0.7mm.

“When you look at the percentage of gold at Egina so far in that category, it’s the bulk of it.”

The nuggets at Novo’s projects vary in size from “very fine gold” right up to “coarse chunky pieces”.

Humphryson says mechanical ore sorting does not require water, chemicals, waste dumps or tailings dam, making it cheaper than other processing options.

“At Egina, you’re basically harvesting nuggets from a deposit that’s less than 2m deep in free dig material for as far as you can dig,” he told Stockhead.

“We think we could put a production set of ore sorters and screening plant together. If you get about six of them, you’re looking at about $10m all up.

“The sorters are about $1-1.2m each, you can get them cheaper, and you need a screening plant ahead of it. So you could have a production unit for $10m that you can use for as long as you want to use it at low cost.”

Despite investors steering away from the conglomerate-gold story, Novo has a fairly decent market cap of over $C740m ($772m) and has continued to trade steadily between $C2.50 and $C4 per share over the past year.

At the peak of the conglomerate gold excitement, Novo reached a share-price high of $C8.83.

Hennigh says the catalyst for again igniting investor interest in the story will be Novo reaching production.

“A lot of people are like ‘uh these guys are whacky, they’re doing this weird conglomerate gold stuff, we don’t know if it’s going to work’,” he explained.

“The proof is in the pudding right. I think once people see us take these things into production and they can actually see you can produce gold bars from these very weird esoteric deposits, you’ll see a respect for the story and people will, I think, understand you can actually make this work.

“That is our chief goal right now is to attain production.”