Australian iron ore could be moving into a new super cycle

Mining

Mining

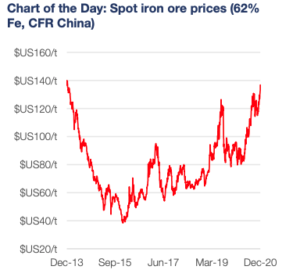

Australian iron ore is commanding prices of $US138 per tonne ($185.70/tonne) in the international spot market, a level last seen seven years ago at the height of the China commodity boom.

The rise in iron ore prices has been triggered by a combination of factors, including reduced output from Brazilian iron ore miner Vale, and China’s accelerating steel production.

Some analysts, including at investment bank Goldman Sachs, suggest China-driven commodity markets like iron ore could be verging on a new super cycle of the ‘stronger for longer’ kind.

In a report Goldman Sachs said governments around the world including in Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC countries) have brought forward new green infrastructure policies to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.

These policies are likely to “create cyclically stronger, more commodity-intensive economic growth, that should create the elusive cyclical upswing in demand”, as reported by Reuters.

But other analysts are less sure, suggesting the jump in iron ore prices could be temporary.

“The recent surge in iron ore prices to multi-year highs suggest that prices are more likely to decline from here over the next 12 months,” said Commonwealth Bank of Australia analyst Vivek Dhar in a report this week.

“China’s demand impulse should eventually weaken at some point next year, especially as China’s fiscal policy will likely move away from supporting China’s commodity intensive sectors,” he added.

China’s strong economic recovery after the coronavirus pandemic has surprised many analysts, and its extra spending has triggered additional steel production.

“The more that governments stimulate their economy through infrastructure spending, the more that is going to translate to demand for steel,” said Mark Eames, director of Magnetite Mines (ASX:MGT).

His company is targeting Chinese ore demand through its Razorback project that is under development in South Australia.

The Chinese government’s Belt-and-Road initiative for roads and rail infrastructure is also consuming lots of steel.

“The iron ore price is very strong which is being driven by Chinese stimulus to their economy and this is pushing up demand for steel and consequently iron ore,” William Johnson, managing director of ASX iron ore company Strike Resources (ASX:SRK) told Stockhead in November.

“And then there is a supply constraint in Brazil due to continued issues with tailings dams and COVID-19: these two factors, demand growth in China and reduced supply from Brazil, are keeping prices high,” he said.

Strike Resources recently completed a feasibility study for its Paulsens East project in WA.

China’s steel production was already growing at a rate of 4 per cent per year for the past 20 years, before the output acceleration sparked by its pandemic response.

“We expect China’s steel demand will register growth in the low single digits in both 2020 and 2021, in contrast to the general decline elsewhere in 2020,” said analysts at S&P Global Ratings in a report this week.

Economists have used the concept of steel intensity to forecast the shape of a country’s steel demand, in that it usually rises as industrialisation occurs, peaks, and gradually tails off.

The issue for economists is that China’s steel production growth has gone on for longer than expected.

“China has defied all expectations in terms of the size of its peak, and so, no one really knows what is going to happen,” Eames said.

Countries like the UK, Germany and US took 20 to 100 years to reach peak steel intensity.

These countries have typically stayed close to their peak, Japan is very close, and that is before mentioning up-and-coming economies in India and Africa.

“Each of those regions has a population roughly the same or larger than China. Even maintaining this level of global steel production is really stretching the ability of the iron ore industry to supply,” said Eames.

Higher iron ore prices are unlikely to lead to demand destruction for the product, he said.

This is because steel manufacturers will simply pass through the extra cost to consumers.

A typical motor car uses about one tonne of steel, which equates to 1.6 tonnes of iron ore costing about $US220 at current spot prices, a small proportion of its total production cost.

“Steel makers are used to fluctuating iron ore prices since the market turned to spot in 2009, and the cost just gets passed on. So, steel making profitability is independent of the iron ore price,” he said.

Also, the other main input to steel production, coking coal, is currently going down in price thereby offsetting some of the rising cost of iron ore.

Vale has revised lower its iron ore output this year to 300 million to 305 million tonnes, down from an earlier figure of 310 million tonnes, said a company statement, Tuesday.

This reduction is equivalent to about 0.5 per cent of global seaborne iron ore supply.

Vale has forecast an output of 315 million to 335 million tonnes from its production capacity of 350 million tonnes for the 2021 year, up from a capacity of 320 million tonnes in 2020.

Market experts said that Vale’s lower-than-expected production will leave China having to find at least 20 million tonnes of iron ore from alternative supply sources in 2021.

The Brazil-based miner wants to achieve a production capacity for iron ore of 400 million tonnes in 2022, rising to 450 million tonnes as a longer-term goal.

Added to this, is the threat of cyclones to Australia’s iron ore industry that could swipe more tonnes from the market in early 2021.

Iron ore has been heading into a tight supply situation for the past few years, according to some market experts who foresaw the present market conditions.

Five years ago — a time of oversupply for the iron ore industry — China was producing 800 million tonnes of steel per year.

That production figure for China had ballooned to 1 billion tonnes in 2019 and, is currently running at 1.1 billion tonnes on an annualised basis in 2020.

“That extra 300 million tonnes requires in the order of 400 million tonnes of iron ore, as there is 1.6 tonnes of iron ore to one tonne of steel,” said Eames.

“In the same five-year period, annual iron ore supply out of Australia and Brazil has gone up by less than 50 million tonnes,” he said.

This indicates a notional shortfall in the iron ore market for China alone of 350 million tonnes, before taking into account any supply hiccups such as in Brazil.

For the world’s four major iron ore producers, BHP (ASX:BHP), Rio Tinto (ASX:RIO), Fortescue Metals Group (ASX:FMG) and Vale, their combined output has risen by only 5 per cent on five years ago.

On top of this, steel production is increasing in other Asian countries — Vietnam has tripled its steel production in the past five years – and this is adding to the iron ore supply crisis.

Asian countries are following China in terms of urbanisation and industrialisation which is steel intensive, adding to ore demand.

“As I look around the industry, there is only one major new mine that is going to produce shortly, BHP’s South Flank, but that is a direct one-to-one replacement for its 80 million-tonne per year Yandi mine,” said Eames.

“Not a single extra tonne of supply will come out of that $4bn investment,” he said.

Rio Tinto is constructing its Koodaideri mine for 43 million tonnes per year, and Fortescue is building its Eliwana and Iron Bridge projects together adding 190 million tonnes per year.

Both companies’ projects are mostly to replace production from existing mines.

Iron ore reserves for Rio Tinto’s existing mines is approximately 2 billion tonnes.

At its current rate of shipping at 320 million tonnes per year, these reserves could be used up within six years.

“Effectively, the major iron ore miners need to build two or three new mines every year just to sustain their output,” said Eames.

“You have got to see a continual pipeline of new production. You have to run to stand still,” he said.

Hancock Prospecting’s 70 per cent-owned Roy Hill iron ore mine has a steady production of about 60 million tonnes per year.

The Sino Iron ore mine in WA operated by Chinese company Citic Pacific Mining produced 20 million wet metric tonnes in the 2019 financial year, and this is expected to remain steady in the 2020 FY.

The long gestation period for iron ore projects means it will take some time for the industry to respond to price signals indicating increased demand for the commodity.

It can take Australian iron ore projects in the realm of 10 years to go from initial study phase through to production and first ore on ship.

There are other iron ore projects planned for WA, but several are quite a few years away from production phase, said Eames.

West African iron ore projects have been touted as a supply solution to increasing steel demand, but none has yet been realised.

Meantime, a number of companies have sunk huge amounts of time and capital into projects in Guinea with little to show for it.

“Africa produces less iron ore than it did in the 1960s,” said Eames, an industry veteran who has worked on projects the world over.

The wheel has therefore turned full circle back to Australia, and its industry’s capacity to meet future market demand.

“In my view, iron ore has relatively strong demand, restricted supply, and good fundamentals if you are an emerging producer,” said Eames.

There are a number of nimble-footed iron ore companies that are looking to capitalise on these market factors.

They include Iron Road (ASX:IRD) with its Central Eyre and Gawler projects in South Australia, and GWR Group (ASX:GWR) which starts production from its WA project in 2021.

There is also Flinders Mines (ASX:FMS) with its Balla Balla project in WA, and partly owned by New Zealand’s Todd Minerals.

At Stockhead, we tell it like it is. While Strike Resources and Magnetite Mines are Stockhead advertisers, they did not sponsor this article.