You might be interested in

Mining

BHP Results: The long, nervous wait to see if Nickel West survives continues

Mining

Rio Results: Rio falls short of expectations on iron ore and copper in March quarter, but says 2024 is on track

Mining

Mining

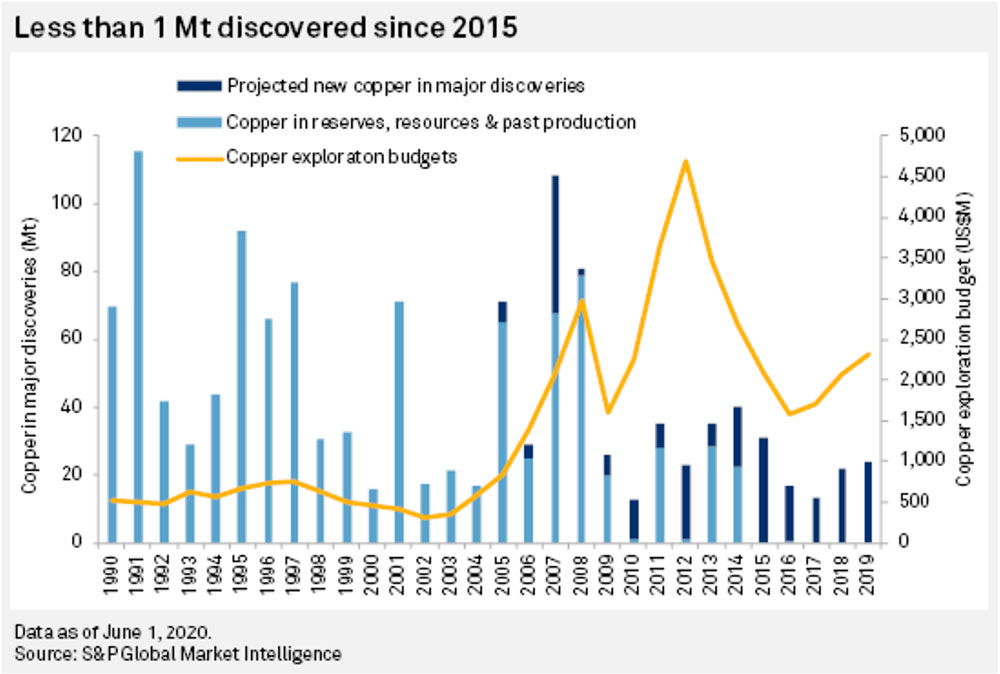

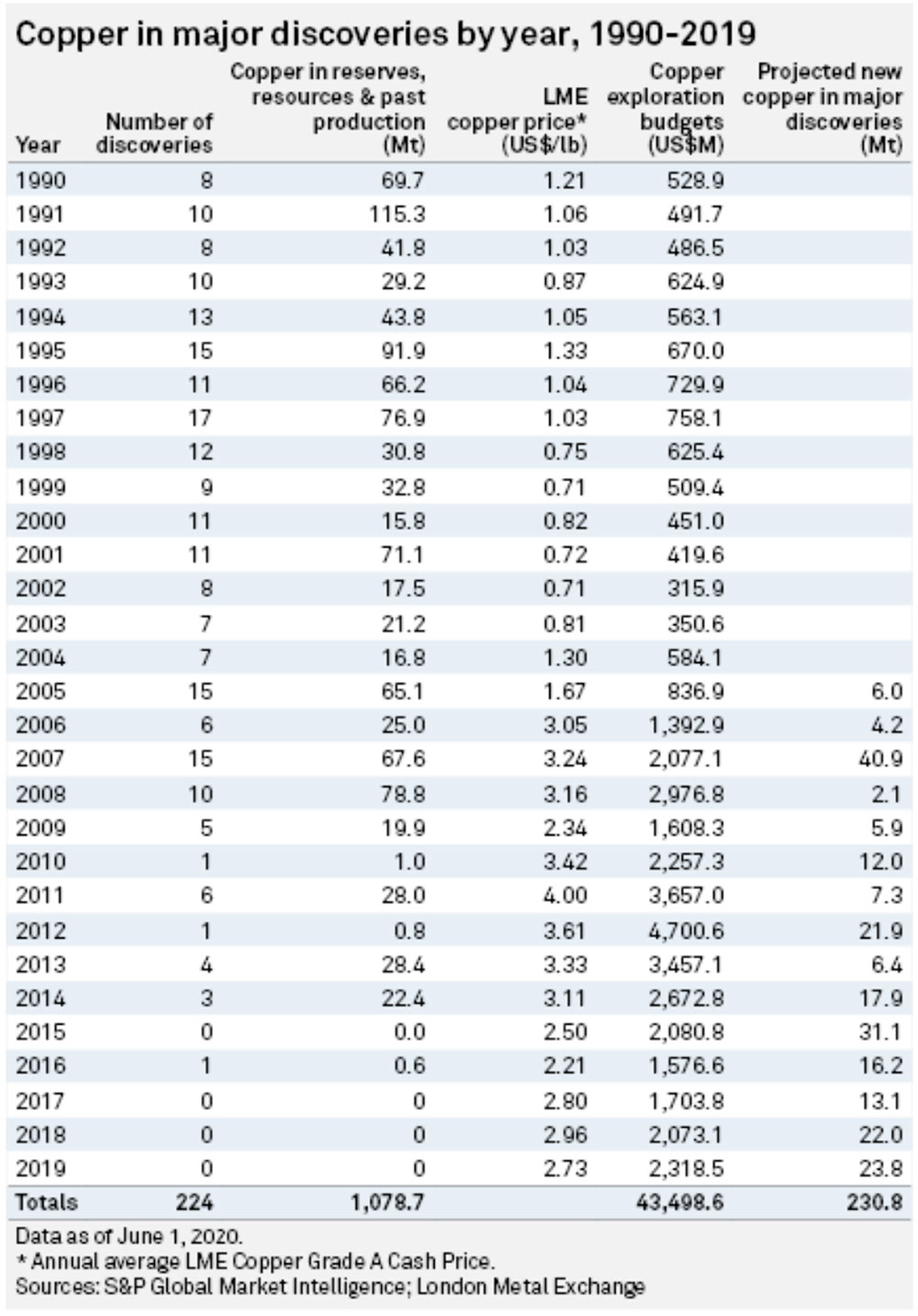

Of the 224 significant copper deposits discovered globally over the past 30 years, only 16 have been found in the past decade — and just one since 2015.

Those 16 deposits contain a paltry 8 per cent, or 81.3 million tonnes, of all copper contained in discoveries since 1990, according to S&P data.

“While there is still an abundance of undeveloped discoveries, most are smaller or low grade, with relatively few high-quality assets available for development,” S&P Global’s Kevin Murphy says.

“Over the next five years, only seven of the undeveloped discoveries are expected to begin production.

“Even when the additional exploration efforts are completed over the coming years, 2010-19 will remain the worst decade for copper discoveries that we have recorded.”

This is important, because plenty of people believe that growing demand for electricity grids, electric vehicles and appliances will widen deficits in the market.

The discoveries dataset prepared by S&P Global Market Intelligence includes all deposits containing at least 500,000 tonnes of copper in reserves, resources and past production.

This is why greenfields or grassroots discoveries like BHP’s Oak Dam and Rio Tinto’s Winu aren’t included – there’s no resource yet.

Grassroots, or greenfields, exploration occurs in a previously unexplored or underexplored areas. For explorers it is high risk, but very high reward.

This lack of major discoveries is mostly the result of less ‘frontier’ exploration.

Since the 1990s, the industry has halved its share of copper budgets devoted to ‘grassroots’ exploration, with the 36 per cent allocated in 2019 near the low of 32 per cent set in 2009.

Companies are focusing more on established assets: juniors at projects with established resources, and majors at and around their mine sites, Murphy says.

“Although some new major discoveries have been found at late-stage projects and existing mining camps, the probability of finding new major discoveries at such projects is lower than at riskier, early-stage prospects,” he says.

Discovery has been weak, slow and top heavy.

The four largest deposits account for 75 per cent of the contained copper found in this decades 16 discoveries.

The biggest is Ivanhoe’s 18.9-million-tonne Kakula deposit, discovered in 2014 during a brownfields exploration program around its Kamoa deposit. The $US1.3bn ($1.9bn) development of Kakula is underway, with first production expected in late 2021.

The Timok project in Serbia, owned by Zijin Mining Group, hosts 15.5 million tonnes of copper and is expected to produce 86,000 tonnes of copper annually. First production is also scheduled for 2021.

Then there’s the earlier stage projects, like the 15-million-tonne Onto deposit in Indonesia and SolGold’s high profile 11.2-million-tonne Cascabel project in Ecuador.

The other issue is that the bulk of the major discoveries made since 1990 are not yet in production.

There are 144 deposits containing 620.4 million tonnes of copper in various stages of assessment and development – which seems like a lot – but most are too small or too low grade.

“Only 16 of these undeveloped assets have more than 10 million tonnes of copper in reserves and resources, enough to support a large copper mine over a mine life of at least 20 years, and only five of the 16 have a copper grade over 1 per cent,” Murphy says.

“A large majority of copper assets are small or have a copper grade below 0.5 per cent.”

Over the next decade, only three deposits discovered since 1990 are almost guaranteed to start production, as they are currently under development. A further four assets will probably come online by 2030.

More big copper mines will be required in the medium term as existing operations ramp down or close, Murphy says.